Sughra Raza. A Murder …. Rwanda, January, 2016.

Digital photograph.

Sughra Raza. A Murder …. Rwanda, January, 2016.

Digital photograph.

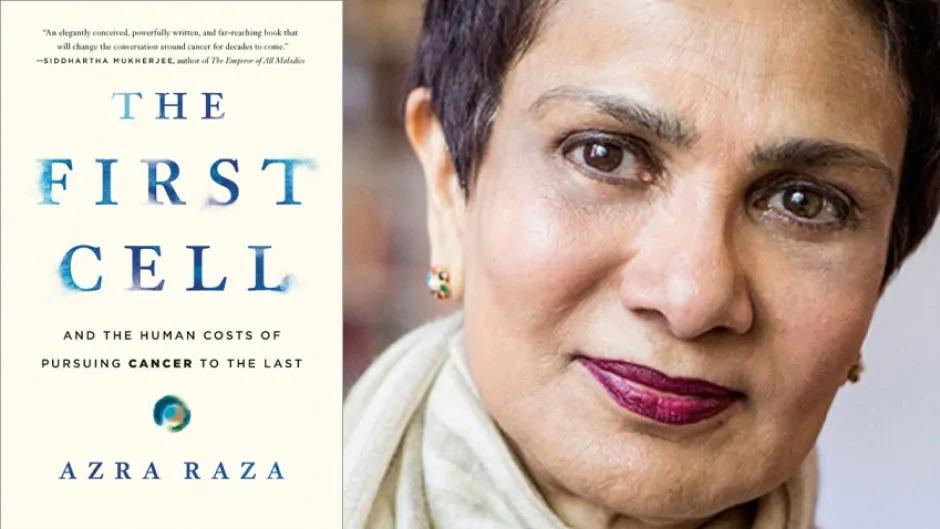

Editor’s Note: This is a letter sent by Dr. Audeh to my sister about her recent book, The First Cell: And the Human Costs of Pursuing Cancer to the Last, and I am publishing it here as a review with his permission.

by M. William Audeh

May 26, 2020

May 26, 2020

Dear Azra,

I am happy to inform you that upon the end our phone conversation, I opened your book, which had been on my Kindle since its publication, and read it over the long weekend.

My apologies for not having read it earlier, but I had my reasons, which I will explain below. However, let me begin by saying that I thoroughly enjoyed your book, not least because your passionate voice comes through the pages so clearly in your writing. I feel as if I have had the privilege of spending several evenings in your lucid company, discussing these fundamental scientific ideas and sharing the heartfelt sorrows. It is eloquent and wonderfully written; a deeply passionate yet sharply rationale argument and memoir. Congratulations!

I will confess, that although I was quite interested to read your book, having spoken with you about its inception, development and impending publication, I was ultimately hesitant. My reluctance stemmed from two regrettable impulses, about which I am not proud, but will readily admit to you, as a dear friend. One was simple jealousy, that you had written and published a book which expressed your long-held beliefs, and anger at myself, for not having found the time and energy to do so myself. Perhaps reading your book will now inspire me to write my own. The other source of my hesitancy was the belief, not entirely unfounded, that I would find myself disagreeing with you on many points of your discourse and did not want to experience that discomfort in relation to you as a friend and colleague. In truth, I am in agreement with you on so very many aspects of your book, that I feel foolish in having held that concern. However, now that I have read your work, and understand the manner in which you have chosen to lay out your argument, I would like to express my thoughts on what you have written. Read more »

by Ashutosh Jogalekar

“All experience shows that even smaller technological changes than those now in the cards profoundly transform political and social relationships. Experience also shows that these transformations are not a priori predictable and that most contemporary “first guesses” concerning them are wrong.” – John von Neumann

Is the coronavirus crisis political or technological? All present analysis would seem to say that this pandemic was a result of gross political incompetence, lack of preparedness and impulsive responses by world leaders and government. But this view would be narrow because it would privilege the proximate cause over the ultimate one. The true, deep cause underlying the pandemic is technological. The coronavirus arose as a result of a hyperconnected world that made human reaction times much slower than global communication and the transport of physical goods and people across international borders. For all our skill in creating these technologies, we did not equip ourselves to manage the network effects and sudden failures in social, economic and political systems created by them. An even older technology, the transfer of genetic information between disparate species, was what enabled the whole crisis in the first place.

This privileging of political forces over technological ones is typical of the mistakes that we often make in seeking the root cause of problems. Political causes, greatly amplified by the twenty-four hour news cycle and social media, are illusory and may even be important in the short-term, but there is little doubt that the slow but sure grind of technological change that penetrates deeper and deeper into social and individual choices will be responsible for most of the important transformations we face during our lifetimes and beyond. On scales of a hundred to five hundred years, there is little doubt that science and technology rather than any political or social event cause the biggest changes in the fortunes of nations and individuals: as Richard Feynman once put it, a hundred years from now, the American Civil War would pale into provincial insignificance compared to that other development from the 1860s – the crafting of the basic equations of electromagnetism by James Clerk Maxwell. The former led to a new social contract for the United States; the latter underpins all of modern civilization – including politics, war and peace.

The question, therefore, is not whether we can survive this or that political party or president. The question is, can we survive technology? Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Joan Harvey

I learned in New Jersey that to be a Negro meant, precisely, that one was never looked at but was simply at the mercy of the reflexes the color of one’s skin caused in other people. —James Baldwin, Notes of a Native Son

I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me. —Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man

…American society is blind to hundreds, even thousands of murders perpetrated in its name by agents of governments. — John Lewis

I had begun thinking about how the coronavirus made very visible the shambles of our society, when the murder of George Floyd took place. Disasters pull aside the veil, and make an underlying reality more apparent. Already the coronavirus had exposed the reality of racism, capitalist economics, the weakness of our food system, our health care crisis, the extreme vulnerability of so many populations, and the built-in structural violence. The George Floyd murder, and the subsequent protests and riots, were police brutality made visible, and rage against the brutality made visible.

Activist and epidemiologist Gregg Gonsalves, referring to the way the virus has been mishandled, asks:

How many people will die this summer, before Election Day? What proportion of the deaths will be among African-Americans, Latinos, other people of color? This is getting awfully close to genocide by default. What else do you call mass death by public policy?

His comments apply equally to the public policy that allows so many to be killed by police. Writing in 2014, civil rights leader John Lewis mentions a recent study that reported that “one black man is killed by police or vigilantes in our country every 28 hours, almost one a day.” Read more »

by Maniza Naqvi

Have a look at the New York City Budget for the fiscal year 2020 and you will very quickly note the priorities (policing) for public expenditures and for cuts (social services of health, education and youth services). A quick back of the envelope public expenditure review reveals and illustrates the fiscal story for the fault-lines nourishing and giving free rein to the virility of both viruses of anti blackness and of the pandemic. And this is the story of masked interventions for maintaining inequity and cruelty in one of the great cities of the world, one of the so called most ‘progressive’ cities of the world.

Have a look at the New York City Budget for the fiscal year 2020 and you will very quickly note the priorities (policing) for public expenditures and for cuts (social services of health, education and youth services). A quick back of the envelope public expenditure review reveals and illustrates the fiscal story for the fault-lines nourishing and giving free rein to the virility of both viruses of anti blackness and of the pandemic. And this is the story of masked interventions for maintaining inequity and cruelty in one of the great cities of the world, one of the so called most ‘progressive’ cities of the world.

About six years ago a colleague of mine and I visited the Human Services of New York City to learn about its Social Safety Net. As the presentation was made to us at City Hall, we found ourselves marveling at and impressed by the size of the City budget of nearly US$ 100 billion. As Development specialists, we were used to working in countries whose entire budgets were dwarfed compared to the New York City budget. However, we found ourselves exchanging glances of how the entire budget including the Human Services and benefits in the city seemed to be of a mindset that the resident beneficiaries have an existing or an expected record of criminality. Therefore a review and reallocation of funding must de-criminalize the orientation of the budget from policing both in percentage and absolute amounts. And every single line item of the budget should be expunged of its relationship to policing. Read more »

17 April 1958

Your Excellency,

thank you for the portrait

of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk who yanked

women of Turkey kicking and screaming

into the 20th century.

Please accept this modest shawl I promised.

Every stitch has been hand-embroidered

by the blessed women artisans

of Kashmir who have spilled their sadness

with threads and barbed wire, weaving

the wrath of history.

An iron necklace frames the square shawl.

Four doves with broken wings sit in corners.

Himalaya gallops the wind.

A river rises to discover clouds.

A moon in the center grins

back at a helmeted head

shooting at her, as you will see.

The blessed women artisans

of Kashmir convey best wishes

to the brave daughters of Turkey.

I hope Ankara undoubtedly supports

our right to self-determination. We

have been fighting long for freedom.

We thank you and your country

for the goodwill you have shown.

Yours faithfully, Mrs. Maryam Jan,

Katrina Bungalow, Pindi Point,

Murree, West Pakistan.

by Rafiq Kathwari / @brownpundit

by Charlie Huenemann

In thinking about knowledge and consciousness, it is just about irresistible to distinguish between the basic facts of what we observe and interpretations or beliefs about those facts. You and I see the same glass of water – maybe our perceptions of the glass are nearly identical – and yet you see it has half full while I see it as half empty. We look at the same economic reports, and you find reason to celebrate while I find cause to worry. We see an artificial satellite in orbit, and you see it an incursion of government and industry into space while I see it as a glory of science and engineering. And so on – it seems obvious that there is a divide between what everyone can plainly see and what’s a matter of interpretation.

In thinking about knowledge and consciousness, it is just about irresistible to distinguish between the basic facts of what we observe and interpretations or beliefs about those facts. You and I see the same glass of water – maybe our perceptions of the glass are nearly identical – and yet you see it has half full while I see it as half empty. We look at the same economic reports, and you find reason to celebrate while I find cause to worry. We see an artificial satellite in orbit, and you see it an incursion of government and industry into space while I see it as a glory of science and engineering. And so on – it seems obvious that there is a divide between what everyone can plainly see and what’s a matter of interpretation.

Descartes was scrupulous about this distinction as he inched his way through the Meditations, continually asking himself what he was really experiencing, as opposed to the judgments he was making about the experience. Do I experience my hands? Or do I only experience the visual and tactile data suggesting that I have hands? Can I infer the existence of the material world from what I experience, or are there other ways of interpreting the sensations that do not suppose there is an external world? Evil genius, anyone? Brain in a vat?

It’s this line of thought that led some philosophers to postulate sense data, or private mental packets of experience whose esse is their percipi, meaning that they don’t exist as anything other than sensations. You see the flower in the vase; I do too, but since I’m across the table from you, my sensations are different in some ways. The colors are the same, or close to the same, but the arrangement is different because of our different perspectives. Different perspectives yield different sets of sense data; that’s what makes them different perspectives. Read more »

by Andrea Scrima

Lydia Hamann and Kaj Osteroth have been working as a collaborative team since 2008. I got to know them in January and February of this year, when they began a year-long residency at the Villa Romana in Florence that was abruptly cut short in early March by the pandemic and the lockdown measures that followed. Hamann and Osteroth studied fine arts in Berlin; their collaborative works—conceptual, feminist, immersed in dialogue and rife with external reference, with one foot firmly planted in queer theory and the other in visual studies— have already acquired an encyclopedic character and have been shown internationally to great acclaim. Their Radical Admiration project spans an impressively prolific period of artistic cooperation that has gone beyond mere rediscovery to critically and convincingly revise historiography and correct the erasures of seminal women artists from the contemporary canon.

Andrea Scrima: Kaj, Lydia, the two of you have been working together on a long-term painting project commemorating a selection of contemporary women artists; over the course of the past thirteen years, a large body of work has evolved that’s attracted the attention of international curators. How did the idea of collaborating first come about?

Kaj Osteroth: The beauty about a long-term collaboration like ours is that the story has been re-written and adapted as we’ve gone along. And each of us recalls a slightly different version.

I like to remember the beginning as a tiny but sparkling, breathtaking first thought: ***this might work***!!! Which became a practice and an even more serious commitment towards one another. That was in 2007, when Lydia and Emma Williams were putting together a workshop for Lady-Fest and invited me to become part of the small initiating group. The idea of continuing to work together was born in never-ending summer talks between Lydia and myself, most likely involving many other people, almost all over Berlin. Today it feels as though we had been meandering and tingling all summer long, until I moved into Lydia’s shared studio space and we began to give our words visual shape. The fact is, we actually started painting much later, because in 2007 we were both still busy finishing university, writing and trying to satisfy the requirements of the academic system. Read more »

by Thomas O’Dwyer

After suffering the injury of pandemic isolation for most of the year, the pride of Dublin city had insult added in May when a national treasure, Bewley’s Café, announced that its doors would be closed not just for the lockdown, but forever. Public outrage rippled out of the city and across the country. Newspapers, blogs and radio programmes lamented the passing of a legend. Bewley’s was the only café in Dublin whose aura, history, and place in people’s hearts could equal the legendary European coffee houses of Paris, Vienna and Venice. Public anger was especially sharp because vanishing customers did not cause the closure.

Bewley’s landlord, an unpopular property mogul, refused to give the café any relief on its annual rent of €1.5 million to ease it through the Covid-19 lockdown, forcing it to close and fire its 110 employees. Print media and the airwaves filled with hundreds of anecdotes and memories from the café’s golden days as “the heart and the hearth” of the city, as the magazine Journal called it. Bewley’s, the “legendary, lofty, clattery café” has always been associated with Leo Maguire’s song Dublin Saunter, a virtual anthem of the city:

“Dublin can be heaven

With coffee at eleven

And a stroll in Stephen’s Green…

Grafton Street’s a wonderland.

There’s magic in the air.

There’s diamonds in your lady’s eyes,

And gold dust in her hair.”

Bewley’s Oriental Café, on the city centre’s stylist Grafton Street, was founded by an English Quaker family who started by importing Chinese tea to Ireland in the 1830s. Ernest Bewley opened his first coffee shop in 1840, followed by a second one soon after on Westmoreland Street, boasting of coffee that was “rich, strong and aromatic, fresh roasted and ground daily on the premises.” Read more »

by Carol A. Westbrook

We think about our fathers during the month of June. Father’s Day is a time to remember these beloved men, especially those who have passed. We reflect on how remarkable their live were, and of so many questions we’d ask them if they were still alive. I’ ask my Dad what he would have done if we were living together at home during the Covid-19 epidemic.

Actually, I don’t need to ask him; I know exactly what he’d do. He’d have followed the guidelines to the letter. He would set the family rules: 1. Masks and gloves when we go out — and no more family drives for hot dogs, Italian beef, or ice cream cones. 2. Wash hands a lot. 3. (That’s me in 1956, doing the right thing!) Play only in our yard, and not with other kids–so no more wiffleball games in the alley, or running under the sprinkler on the front lawn. 4. Meals together, as usual. 5 Pray together as a family every night. For supplies, he’d take advantage of our well-stocked basement “bomb shelter” storage, pantry and deep freezer.

Dad would have obtained supplies for the lockdown using connections at his workplace, the Chicago Board of Education. In true Chicago style, he would call in favors or promise favors of his own, like a good word to a Department head for a city job. Or he could offer professional family portraits, or wedding photos. He also had gossip and information to share. Read more »

by Emrys Westacott

When I feel myself becoming irritable, disheartened, or just plain fed-up with life during the pandemic, I find it helpful to conduct a thought-experiment familiar to the ancient Stoics. I reflect on how much I have to be grateful for, and how things could be so much worse. That prompts the more general question: Who are the fortunate, and who are the unfortunate at this time?

When I feel myself becoming irritable, disheartened, or just plain fed-up with life during the pandemic, I find it helpful to conduct a thought-experiment familiar to the ancient Stoics. I reflect on how much I have to be grateful for, and how things could be so much worse. That prompts the more general question: Who are the fortunate, and who are the unfortunate at this time?

Let’s consider the unfortunate first. These include:

As for the fortunate, these include:

It is the last category in each of these groups that I want to talk about. Read more »

Sughra Raza. The People, They Speak. Graffiti, Valparaiso, Chile, November, 2017.

Digital photograph.

by Ruchira Paul

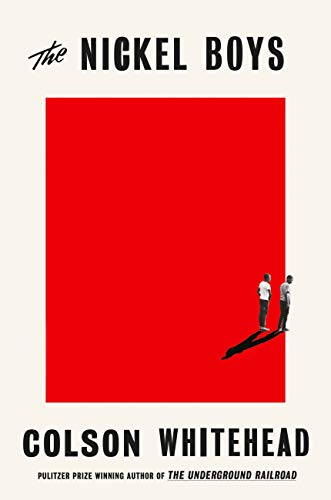

“In New York City there lived a Nickel Boy who went by the name of Elwood Curtis…

When they found the secret graveyard, he knew he’d have to return. The clutch of cedars over the TV reporter’s shoulder brought back the heat on his skin, the screech of dry flies. It wasn’t far off at all. Never will be.”

Colson Whitehead won his second Pulitzer Prize for The Nickel Boys in 2020, joining the ranks of three other writers recognized for the rare honor. His first was for another historical fiction The Underground Railroad in 2017. What are the odds of winning the Pulitzer for two books that deal with the same subject – the troubled race relations in America? Pretty good, I would say, if your second book is as brilliant as The Nickel Boys.

Colson Whitehead won his second Pulitzer Prize for The Nickel Boys in 2020, joining the ranks of three other writers recognized for the rare honor. His first was for another historical fiction The Underground Railroad in 2017. What are the odds of winning the Pulitzer for two books that deal with the same subject – the troubled race relations in America? Pretty good, I would say, if your second book is as brilliant as The Nickel Boys.

The Nickel Boys is a searing account of life in a boys’ reform school, the Nickel Academy, in Jim Crow era Florida where the book’s protagonist Elwood Curtis spent some time in the early 1960s. Based on a real life institution, the Dozier School for Boys (now closed) where an unmarked graveyard was unearthed in 2012, the book begins with a reference to that gruesome discovery. The skeletons and bone fragments of young adolescent boys that emerged pointed to violent deaths due to broken bones, caved in skulls, bullet wounds and severe malnutrition. Whitehead’s novel takes us on a journey beginning with Elwood’s early days of a mostly happy, placid and hardscrabble life under his grandmother’s watchful loving care. (His parents had abandoned him when they decided to escape the oppressive racism of Florida to seek a brighter future in California). A bookish, earnest and ambitious boy, he spent his days studying diligently in school and his spare time reading whatever books, magazines and newspapers he could lay his hands on. As a teenager he eschewed the pranks and pastimes of his peers and held down a part time job in a cigar shop owned by a kindly Italian American man whom he impressed with his meticulous work ethics.

When he was not reading, working or doing household chores, Elwood listened to a scratched up LP of MLK Jr’s speeches – “Martin Luther King At Zion Hill,” whose contents both inspired and mesmerized. Around him the great ferment of the civil rights movement was unfolding and he hoped to be a part of it. Read more »

by Abigail Akavia

“I was surprised you didn’t start with Philoctetes,” my advisor tells me after my dissertation defense. In our institution, in the crowning moment of a student’s academic career, she is expected not only to publicly display sufficient knowledge in her research field, but also to narrate the ‘making of’ the dissertation topic. Indeed, Sophocles’ Philoctetes could be considered the play that brought me to graduate school to begin with. The dynamics of compassion, suffering, and language in this play are paradigmatic to the questions that shaped my research; a few years out of school, I still can’t (nor want to) get away from this play (and I even wrote about it here once before).

And yet, when presenting the retrospectively made-up timeline of how my research came together, the point where I claimed “it all started” was not Philoctetes, but Sophocles’ most famous play, Oedipus Tyrannus. I did so because I had the opportunity, while in grad school, to direct the play (we’ll call it OT henceforth), an experience that was quite unlike anything else I did as a student, and which was crucial for shaping my academic project. I knew I was interested in the Sophoclean chorus, but only through having to solve for myself the dramaturgical and choreographic ‘problem’ of putting a bunch of seemingly extra bodies onstage who lament Oedipus’ fate did I truly realize how dramatically pregnant this community of vocal witness-bearers is. Working on transforming the script into a performance was a turning point in my engagement with Sophocles, coalescing what I’d learned about his plays and my own interests and hunches about them into a tangible, clear perspective. I came to view the exploration of people’s (in)capacity to be with another person’s pain—or, in other terms, the community’s involvement and reaction to an individual’s tragedy—as one of the driving forces of Sophoclean drama. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Joseph Shieber

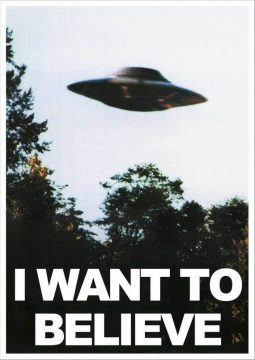

Recently I was reading one of Scott Alexander’s posts about fake news and conspiracist thinking. In that post he introduces what he dubs the “North Dakota Constant”.

Alexander references a survey conducted by researchers at Chapman University, and mentioned a “control question” that the researchers included in the survey.

Here’s how the pollsters at Chapman describe that question and the responses it prompted:

Perhaps most indicative of the conspiratorial nature of Americans is the …one which, to our knowledge, we created.

Respondents to the Chapman University Survey of American Fears were asked if “The government is concealing what they know about…the North Dakota crash.” A third of Americans (33%) think the government is concealing information about this invented event.

Were the North Dakota crash added to the ranked list of conspiracies (see above), this invention would rank as number six, just under plans for a one world government.

What Alexander concludes from this is that there is a large minority of the country — the 33% willing to buy in to a conspiracy about a “North Dakota crash” that never existed — who are disposed to believe in ANY conspiracy.

Alexander suggests that the existence of the “North Dakota Constant” should make us more cautious in overemphasizing the role of “fake news” in causing conspiracist thinking. His idea is that if there is a floor of over 30% of the population disposed to believe in a made-up conspiracy, the fact that 30% of the public believe that President Obama wasn’t born in the United States is not in fact evidence of a very strong “fake news” effect. That is because, if the “North Dakota Constant” is compelling, we would expect around 30% of the public to believe ANY conspiracy about which pollsters questioned them. Read more »

by Mindy Clegg

The main thing that I learned about conspiracy theory is that conspiracy theorists actually believe in a conspiracy because that is more comforting. The truth of the world is that it is chaotic. The truth is, that it is not the Jewish banking conspiracy or the grey aliens or the 12 foot reptiloids from another dimension that are in control. The truth is more frightening, nobody is in control. The world is rudderless. (Alan Moore in The Mindscape of Alan Moore 2003)

The point of modern propaganda isn’t only to misinform or push an agenda. It is to exhaust your critical thinking, to annihilate truth. (See Garry Kasparov tweet.)

In 2001, filmmaker Richard Linklater released a dreamy follow up to his 1990 film Slacker. Waking Life followed a similar format to Slacker, disconnected vignettes but with an animated overlay. In one scene, Alex Jones makes an appearance. At the time, Jones was not the nationally known influence on a President he is today. He began his career on Austin public access TV, but has since become a popular figure on the far right. At the time, Linklater just saw him as an entertaining and harmless political ranter and gave him two minutes in his meandering film. Read more »