by Andrea Scrima

David Krippendorff is a US/German interdisciplinary artist and experimental filmmaker. Based in Berlin, he grew up in Rome, Italy, and studied art at the University of Fine Arts in Berlin, Germany, where he graduated with an MFA. His paintings, drawings, prints, films, and videos have been shown internationally, including at the New Museum (New York), ICA (London), Hamburger Kunsthalle (Hamburg), and the Museum on the Seam (Jerusalem). He has participated in three biennials (Prague, Poznan, Tel Aviv).

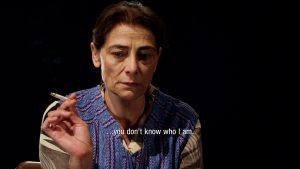

Krippendorff’s short film Nothing Escapes My Eyes is currently part of the group exhibition “The Women Behind” at the Museum on the Seam; it was also shown at the Belgrade City Museum for the 56th October Salon in 2016 and has been screened at numerous international film festivals, winning twice as Best Short Film. Kali, a short film based on Brecht’s Threepenny Opera, also features Palestinian actress Hiam Abbass; it premiered at the Braunschweig International Film Festival in 2017.

Andrea Scrima: David, I’d like to begin with a question about your previous work. For decades now, you’ve been incorporating imagery from popular culture; earlier works, particularly There’s No Place Like Home, Sleeping Beauty, and The Beautiful Island, drew on the hidden subtexts in well-known American movies, such as The Wizard of Oz and Gilda. What was the motivating force behind this line of inquiry?

David Krippendorff: I grew up on classic American movies. The Wizard of Oz was an intrinsic part of my childhood, so it felt very natural to work with these films, because I had a personal relationship to them. My interest was in uncovering the ideologies and desires present in these films, but hidden beneath a polished layer of glamour and storytelling. I’m also fascinated by how thin the boundaries have become between the personal and the mediated experience, and films—with their almost mythological function—are the perfect material for this inquiry.

A.S.: I’m assuming that your own background of multiple cultures and languages—you were born in Berlin, grew up in Rome, and hold American and German passports—has provided emotional fuel for your artmaking.

D.K.: It definitely has.

A.S.: What role does “home” play in your work?

D.K.: I grew up between cultures, and so the concepts of home, belonging, and cultural identity have always been a part of my personal life. I never felt I belonged or could fully identify with any one culture; basically, I feel like a permanent foreigner. This is why The Wizard of Oz was the first film I worked with. Not only was it part of my childhood, but the whole utopian ideal of home that becomes the driving force and moral of the film struck a deep chord inside of me. I fully identified with that desire and with the realization that, contrary to the film’s saccharine conclusion, it’s an impossible utopia. I read a fascinating book about the idea of home in classic Hollywood films, about the fact that it’s such a recurring theme in the films of that time. Many of the writers and directors were themselves Europeans who had fled Nazi Germany and were in exile in the United States. They were implementing their own desires and longings in their work.

A.S.: Your two recent films frame a thematic reference to the Middle East. How did you first begin investigating the cultural and historical legacies of the region?

D.K.: It was a coincidence. The story behind Nothing Escapes My Eyes, which is located in Cairo, began with music: I fell in love with Verdi (I guess my Italian background played a huge role here) and discovered his opera Aida. One of the most interesting themes in this opera is the concept of belonging and assimilation. Aida is in fact a character caught between two cultures: an Ethiopian princess, slave to the Pharaoh who has conquered her country and in love with the Egyptian general, she is torn between two opposing desires, to assimilate in Egyptian society and stay true to her own cultural identity. To me, this conflict is incredibly relevant to our times. I became very excited when I discovered it in Verdi’s music. My inspirations always start with an emotional reaction. There is a moment in the opera when Aida cries out “Oh Homeland! What a high price I pay for you!” The first time I heard this, I got goose bumps and immediately knew that I had to do something with this material, but I had no idea what and in which medium. I started reading a lot about Verdi, about Egypt at the end of the nineteenth century and its colonialist past. When I discovered the story of the opera house in Cairo where Aida had its world premiere, the whole film played out before my eyes.

A.S.: And so you staged Nothing Escapes My Eyes in the parking garage built on the site of the former Khedivial Opera House, where Aida premiered in 1871.

D.K.: Yes, this added another layer of absence to the piece. What intrigued me with the material was that it allowed me to work on many different narrative levels. The works on paper that are related to the film are done with the actual musical score, but cover it with a gold leaf application of an Islamic pattern I found in Cairo, or with the translation in Arabic of excerpts from the libretto, almost as if the real “location” imposes itself on the fictional and “Orientalized” narrative, creating a new and contemporary reading.

A.S.: The work also contains echoes of the destabilization of the Middle East we’ve seen occur over the past decade and a half—as does your new film, Kali. What’s this work about?

D.K.: Shortly after completing Nothing Escapes My Eyes, I started listening to Nina Simone. I heard her rendition of Pirate Jenny from the Brecht/Weil Three Penny Opera, and that provided the inspiration. The rightful anger that she expresses in the song, her utopian desire to experience a just revenge for the abuse and exploitation she’s suffered still felt particularly relevant to our times. I decided to rewrite the lyrics as a monologue and have it performed by women from different cultures, each in their own language. Each one should represent a contemporary situation of exploitation and injustice. Having recently worked with Hiam Abbass, I thought it would be perfect to start with her and have it performed in Arabic, with her playing the role of a cleaning woman. Although she avoided using a strictly Palestinian Arabic in her monologue, one can read in the work the injustice suffered by the Palestinian people. But she could just as easily be a refugee living here in the West. It’s open to multiple interpretations.

A.S.: What role do identity politics play in your artistic thinking? As a Jew whose parents lost a good deal of their family in the Holocaust, declaring your sympathies with the Palestinian plight must have been a very deliberate decision.

D.K.: Although my family is not religious, I grew up acutely aware of my parent’s history. My mother is a Holocaust survivor, having been smuggled into England with the Kindertransport from Czechoslovakia. My father’s family was German and supported Hitler. My father rebelled and became a radical left-wing historian. Having these two backgrounds as part of my DNA is like carrying the weight of the World War II atrocities on my shoulders. With this background, plus my own feelings of cultural displacement, I have a natural inclination to identify with minorities and groups that suffer discrimination or injustice. Sympathizing with the Palestinian plight becomes an obvious choice.

A.S.: Have you ever addressed your Jewish heritage or cultural identity in your work?

D.K.: Let me put it this way: given my background, there was no escape from identity politics for me. It’s not really a choice. But in answer to your question: no, I never directly addressed the fact of being a Jew in my work.

A.S.: In terms of identity politics, it sounds more like the imprinting of that legacy led not to a narrowing of self-definition or a restriction to a single identity, but to a broader identification with the human plight.

D.K.: I hope so.

A.S.: Your work addresses a repertoire of themes: loss of identity, economic exploitation, disenfranchisement. How important is the political subtext?

D.K.: Without wanting to sound naive, first and foremost I hope that my work has a strong emotional impact. Every initial idea I ever had for a piece always started with an emotional reaction to something, be it a film or a piece of music. Throughout the process, I then conceptualize it and parse out the various political subtexts and interpretive layers. I do think that all art is political, but I am also a great believer that art should be more visceral. We live in times in which nobody trusts their feelings anymore; our society is becoming increasingly cerebral. I think this is a very dangerous trend, because remaining in touch with one’s feelings is also the first step toward empathy. When we’re detached, it becomes much easier to turn a blind eye to injustice; we fail to see the humanity in a homeless person we pass by on the street. I strongly believe that the role of art should be to help people get in touch with their feelings. To me, this becomes political, and it’s the only way that it can have an impact and make a change. We have enough “interesting” art, but how often does somebody go to a show and say: “That was really moving,” or “That was beautiful”?

A.S.: To what extent do you think art can provide a conceptual structure for reframing how we question the version of reality the media presents to us?

D.K.: I think artists are the fastest at spotting bullshit, pardon my expression! They understand the power of images and therefore are quicker at noticing when images are manipulating us. There are many artists who operate using media images to reveal their power or hidden agenda, or playing with styles and vocabularies taken directly from the media world, but reshaping them to create their own narratives. It’s a very interesting strategy. I also think that the media landscape for the artists of our time has become what nature used to be for the artists of the past, who sought inspiration outdoors. Our landscape, by contrast, has been taken over by movies, billboards, screens, and computer games.

A.S.: Yes, and many of these artists use social media not merely as a platform for their works, but as an artistic medium and material. There’s a kind of uninterrupted flow happening, an ongoing multivalent polylogue in which meaning, identity, cultural critique, and political understanding are negotiated more collectively than ever before. It’s an experiment, and we’ve seen its good sides and its bad sides. You made a work commemorating the Homeland hack and got a lot of flack for it, didn’t you?

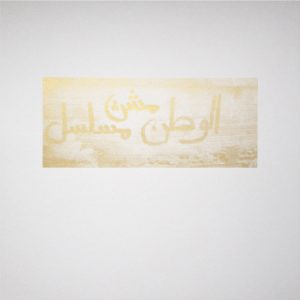

D.K.: Yes. There was an interesting case a few years ago regarding the famous TV series Homeland. When they shot the fifth season in Berlin, they needed graffiti sprayers to make the set of a Middle Eastern city street look more realistic. A group that was hired to spray graffiti on the walls decided to hack the series by writing humorous sentences exposing the racism of the script. Since nobody on the set spoke Arabic (which is already in itself an indication of how superficially the subject matter was being treated), they got away with it. The episodes were aired with phrases like “Homeland is racist” or “1001 Jokes” appearing as graffiti in the background. This is a brilliant example for how one can point out ideological agendas within the entertainment industry. When I produced the golden prints, I unfortunately had no idea that one of the sprayers was an artist. She saw my work at an art fair and became very upset.

A.S.: No one likes to see their work appropriated.

D.K.: Of course not. But it was a celebration of what I took to be a brilliant act of rebellion. I was excited by what they’d done and wanted to call attention to it, pay homage to it. The media coverage that I’d seen didn’t describe the true identity of the hackers, i.e. that one of them, Heba Y. Amin, was a practicing artist.

A.S.: Eventually, though, there was a good deal of more detailed press.

D.K.: I know. Unfortunately, the early reports I read in Die Süddeutsche, Die Zeit, and Der Tagesspiegel misled me into understanding the hack as a purely political gesture as opposed to a political gesture and a work of art—and then most of my focus went into image research.

A.S.: The hack was an incredible act of subversion, and it was right up your alley, as your work has been based on exposing ideological subtexts in popular culture for many years.

D.K.: Yes, that’s why I got so excited about it. Unfortunately, it backfired: to their mind, I was stealing the narrative from the marginalized.

A.S.: The stakes are high when it comes to the way the media portray the region. And so their sensitivity is understandable, considering the fact that the Bush administration, in the aftermath of 9/11, was responsible for destabilizing large parts of the Middle East. Homeland capitalizes on the rampant Islamophobia in America that resulted.

D.K.: Yes, this was precisely the target of their hack. As a viewer, I was equally disturbed by the portrayal of the Middle East in Homeland when I watched the first season. That’s why I loved the hack so much. I screened the images of the graffiti and made silkscreened prints of them in gold to call attention to the way the series profits from the subject matter: taking what has become a living hell for millions of people and turning it into a menacing backdrop for a fairly shallow narrative. The gold has a deeply ambiguous function: it’s both a sign of wealth and economic exploitation and a symbolic way of giving value to this rebellion, but it also visualizes the ephemeral quality of the media, as the image tends to disappear and reappear according to how the light reflects on the printed surface.

A.S.: I can see how the sale of these works can seem like economic exploitation to them.

D.K.: If you completely ignore what the work is, in fact, about, so can I. They subverted the production of the TV series with a political critique that initially went unnoticed, and that, when it finally was noticed, opened up a discussion over racist stereotyping in the portrayal of Middle Eastern identities. By contrast, my works address the reception of these images in the media; they don’t compete with their act of subversion, but reflect on the way it entered the public sphere.

A.S.: What also, perhaps, comes into play here is that Heba Y. Amin, in a series of interviews conducted after the fact, said that the phrases they sprayed arose spontaneously, on site. When they realized how lax the oversight on the part of the set director was, they began playing with words and eventually crossed the line to openly criticize the series, which went on air before the sabotage was discovered. This poses an interesting question about intentionality—one that blurs the line between spontaneous activism and declaring the act to be work of art in retrospect. It’s a problematic position to take—to infiltrate, anonymously, popular culture to reach a wide audience and generate a debate, and then to want to police who reacts to this public act and in what way.

D.K.: You have a good point. I only regret that it wasn’t possible to have a dialogue.

A.S.: Did you try to talk about it?

D.K.: I did, and I even took the works off the wall and literally handed them over to her as a gesture of good faith. But then she went straight to the press, and so the dialogue was shut down before it even got off the ground. At that point, I basically had to protect the rights to my own work.

A.S.: It’s a shame, because you probably have a lot in common as artists.

D.K.: I don’t know. Certainly, being openly accused of white male privilege, being pigeonholed in a way that clearly ignores what I do and what my work is about, is a bracing experience to go through, particularly when you’ve made it your business to defend the disenfranchised. I made the works before I had gallery representation, and all of a sudden I was being accused of entitlement, of capitalizing on someone else’s work, although the short press text accompanying them clearly referred to the images’ origin and the story of the Homeland hack.

These are tough times, politically dangerous times, and people tend to subscribe wholeheartedly to a cause and ignore the rest. There is no longer any room for nuance. But I don’t want to judge. #metoo and Black Lives Matter have opened up very necessary dialogues; we need an equivalent movement to correct the image people in the West have of the Middle East. Racism and sexism are real, and it’s getting worse.

A.S.: But it’s not just a moral question—it’s also a legal question. In the U.S., an important precedent was set by the Blanch v. Koons case of 2006, which established that Koons’ appropriation of an image from a fashion magazine constituted “fair use” and not copyright infringement. The distinction here is that the new work must have a “meaning, message, and character” that sets it apart from the original. In the art world—even among people who hate Koons and everything he stands for—this decision was widely applauded, because it reversed a trend that had begun after Koons lost an earlier copyright infringement suit. As artist Joy Garnett pointed out on Facebook, this was followed by thousands of new lawsuits threatening artists with the destruction and/or censorship of their artworks.

D.K.: Yes, it’s always the prominent cases that make it into the news, but the fact is that many, many artists are impacted by these rulings. To conflate appropriated and derivative imagery with copyright infringement or theft is to misunderstand what artists do. We can’t ignore that technology has made these images reproducible and readily available to all. Artists develop their own relationship to these images and use them to create new works that comment on the culture and society at large.

A.S.: The case of Richard Prince v. Patrick Cariou further cemented the general acceptance of “fair use.” In Germany, this concept is very close to the freedoms accorded “freie Benutzung” as it’s defined in the country’s copyright law.

D.K.: Appropriation has been going on for a long time, in all fields. Especially in music, with sampling, it’s become its own aesthetic category.

A.S.: And there’s the well-known literary scandal of Helene Hegemann and her book Axolotl Roadkill, passages of which were paraphrased from another writer’s blog. Author and publisher defended the practice as part of a long tradition of Dada collage, postmodern intertextuality, sampling, and mashup aesthetic, but to me it seemed like a pretty clear case of plagiarism.

D.K.: I recently read that Brecht had been accused of plagiarism after having borrowed complete sentences from Rimbaud and using them in a play. He had no problem admitting to this. Of course, one can and should distinguish between a creative way of appropriating and a less creative one, but that becomes highly subjective. In the end, the question is what the work expresses, and if it adds anything meaningful to the source material. I always hope to add something meaningful.

A.S.: Can you talk about your next works? Are you planning more of the Pirate Jenny series?

D.K.: The Pirate Jenny films are definitely on my mind, but for these the casting is crucial. I am keeping my radar open, because the choice of actress will also define the idea for the film and the adaptation of the lyrics to the new character. In the meantime, I’m almost finished with the editing and post production of a new film, a “remake” of the opening credits of Douglas Sirk’s Imitation of Life, in which you see diamonds slowly falling from the top of the screen and gradually collecting on the bottom, eventually piling up to fill up the entire frame.

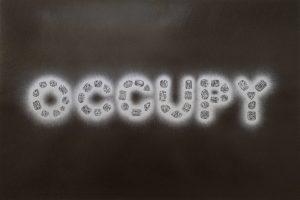

To me, it’s a beautiful metaphor for being buried alive by our material desires, and very much about the present times we’re living in. Alongside this, I’ve been working on a series of drawings depicting diamonds glowing on a black background. The gems are arranged to spell out the words “Home,” “Refugee,” “Occupy,” and “I Can’t Breathe,” catchwords that stand for moments of hope in the political resistance, visualized here as an uneasy reminder of how in our society everything is connected to material values and money.

I’m also currently planning a third film with Hiam Abbass, which would then complete a trilogy exploring issues of identity, exploitation, and loss. The film will be called Appropriation, and as with the previous two films, Nothing Escapes My Eyes (which incorporates Verdi’s Aida) and Kali (which references the Brecht/Weil Three Penny Opera), this film is also connected to a musical score, Maurice Ravel’s version of the Kaddish. A Palestinian woman performing the Jewish prayer for the dead can be seen both as the ultimate act of cultural and religious appropriation and as a form of overcoming hostility through the embracing of the most human and natural condition of all, the one we all share and that ultimately makes us all equal: death.

A.S.: David, I look forward to seeing it when it’s done. Thanks for taking part in this conversation.