by Timothy Don

I met Rene Magritte a few weeks ago at the Starline Social Club in Oakland. A surprisingly jolly fellow, it turns out he’s working these days as a pedicab driver in San Francisco. Surrealism isn’t my jam, but when he offered me a pickup the next morning at the BART and mushrooms and tickets for two to the retrospective of his work at SFMoMA, well—I had to accept.

I met Rene Magritte a few weeks ago at the Starline Social Club in Oakland. A surprisingly jolly fellow, it turns out he’s working these days as a pedicab driver in San Francisco. Surrealism isn’t my jam, but when he offered me a pickup the next morning at the BART and mushrooms and tickets for two to the retrospective of his work at SFMoMA, well—I had to accept.

There are many things one could say about the SFMoMA. It’s massive, it’s powerful, and it’s complicated. I have a sneaking suspicion that it operates as a kind of Leviathan in the Bay Area that sucks aesthetic energy into its great maw, gobbling up the local, less well-endowed swimmers and forcing an evacuation of the surrounding area that threatens to leave the gallery and studio scene like a bleached-out coral reef bereft of any but the largest predators. The regular reports of artists fleeing the Bay Area and moving to Los Angeles would seem to bear this out, as would the wriggling, lamprey-like presence of a Gagosian outpost since 2016 across the street.

That said, the collection SFMoMA contains is nothing short of incredible. Bracketing for the time being the delicious irony of the Fisher holdings—one of the world’s most extensive collections of post-war and contemporary art, a collection of some of the most sublime works of 20th century art, built from a fortune made by erasing the distinction between high and low culture (The Gap), valued at well over a billion dollars—visiting SFMoMA is an eye-widening, jaw-dropping experience. It has everything, all of it, and it is informed by a profound and generous curatorial intelligence. Each visit promises new understandings, a renewed interest in old favorites (“Here’s a room full of Paul Klee!”), and a reminder of what art and artists can do: the limitless reach of human creativity. It doesn’t engage in easy juxtapositions or cheap didactics. It just quietly and seductively invites you to join the conversation. There are some very smart people working there.

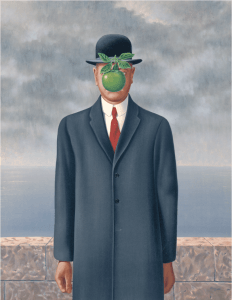

The Magritte exhibit was proof of that. It was exquisitely curated. But whether it was because I didn’t eat the mushrooms or because surrealism is a movement that appeared during the hour when the sun casts its shortest shadow, I found the curatorial effort behind the exhibit more compelling than the work itself. Sorry, but I was underwhelmed. Magritte (for my taste) is neither creepy enough, nor playful enough, nor philosophical enough to warrant bathing with. Spending that much time with that much of his work was a lesson in the limits of puns and dreams. There’s a reason that it appeals to children, and we are not living in child-like times. These are ugly, impoverished times. Wounded times. Magritte doesn’t help us negotiate them. So at the end of it, I went in search of some art that would explode in my face or deepen my emotions or fill me with awe. Give me some Kara Walker, please, or some William Kentridge. Like I said, SFMoMA has it all. Finally, I found myself looking at a bunch of paintings by Philip Guston.

Guston, I realize now, was a perfect antidote to Magritte, and not because he was an early abstract expressionist where Magritte was a surrealist or because his paintings became cartoonish where Magritte’s were almost photorealistic. It’s not about where they oppose one another. It has more to do with what they have in common, and the different places in which each of them land in spite of that commonality, and what those places can tell us about where we currently stand.

They both portray private worlds in their paintings, but Magritte’s privacy is an interior one of rooms and mundane objects and men in suits. The eros in his paintings is an individualized urge that he inflates to grotesque proportions. Magritte goes after the uncanny nature of individual experience, the weirdness of individual life.

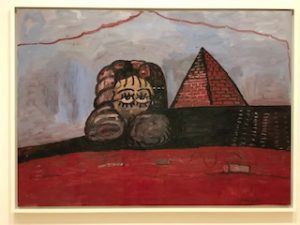

Guston’s privacy is one upon which the outside world is constantly encroaching, so that the singular is always already in relationship to the plural, the public oozes and bleeds into the private, and the individual finds herself thrown into an overwhelmingly large and deeply chaotic world. While they both start from the perspective of the individual at sea in the world, Magritte retreats and drills down into the individual psyche while Guston pushes outward and confronts the world that assaults him. Magritte becomes a surrealist; Guston becomes an existentialist.

They both paint from the perspective of a child. But Magritte is a tidy child who paints very tidily and puts his things away. Looking at his paintings, I am reminded of scenes from my own childhood: staring at a window pane in the rain, watching individual droplets become engorged and swollen, trying to catch and freeze that moment just before a single drop bursts and runs down the glass. Or studying an individual object (a teacup, a hairbrush) until I am so familiar with it that takes on gigantic, overwhelming proportions. Guston also paints like a child, but with a raw and primitive immediacy that verges on messiness and is contained only by his cartoonish style. Magritte is the child who keeps his questions to himself and works them out on his own; Guston is the one who asks after every answer, “Yes, but why?” Magritte takes the terrifying, nightmarish aspects of childhood and paints them into an order that simultaneously deepens those aspects and orders them. Guston presents those horrors in a cartoonish manner, simultaneously recording, confronting, and containing them. Magritte paints dreams and fantasies; Guston paints insults and wounds.

I have always been drawn to Guston’s work and felt it to be deeply relevant to our moment but I didn’t know why until I saw it in the wake of Magritte’s. Even though most of it is almost fifty years old now, it feels absolutely contemporary. These are Gustonian times. The palette is made up primarily of reds, pinks and grays. His paintings are the color of blood (fresh, dried, or stale blood), and each one feels as though something has been torn or ripped in the process of completing it. They are records of insults and crimes and ugly memories, populated by bullies and racists and vulgar tyros, rendered in a style that reveals the juvenile nature of their subjects and the danger they pose–precisely because they are juveniles, boys dressed up as men who have claimed violence as their birthright. Guston painted wounds, personal and political wounds. Looking at them, I feel myself in the presence of a prophet.