by Bill Benzon

How do we get there from here? Evolution, revolution, or revolution through evolution? I don’t know, but as the smart kids are saying these days, I have my priors. As does everyone else.

A movement begins

Back in July 2019 Patrick Collison and Tyler Cowen called for a science of progress in an article in The Atlantic. The article generated a fair response, some in favor, some pushing back – Collison has collected some of the responses here – and people have begun conversing and gathering around the idea of progress studies. The purpose of this post is to take a quick look at what has been going on and a somewhat

more considered look at what needs to happen if an interest in progress studies is to yield discernible progress.

Let’s begin with a passage from Collison and Cowen, “We Need a New Science of Progress”:

By “progress,” we mean the combination of economic, technological, scientific, cultural, and organizational advancement that has transformed our lives and raised standards of living over the past couple of centuries. For a number of reasons, there is no broad-based intellectual movement focused on understanding the dynamics of progress, or targeting the deeper goal of speeding it up. We believe that it deserves a dedicated field of study. We suggest inaugurating the discipline of “Progress Studies.”

Before digging into what Progress Studies would entail, it’s worth noting that we still need a lot of progress. We haven’t yet cured all diseases; we don’t yet know how to solve climate change; we’re still a very long way from enabling most of the world’s population to live as comfortably as the wealthiest people do today; we don’t yet understand how best to predict or mitigate all kinds of natural disasters; we aren’t yet able to travel as cheaply and quickly as we’d like; we could be far better than we are at educating young people. The list of opportunities for improvement is still extremely long.

Mark their reach: cure all diseases, solve climate change, world’s population live comfortably, predict and mitigate natural disasters, travel cheaply, educate all young people well. The words are easy to comprehend, and those two paragraphs are relatively short. But they are talking about human life on earth, all of it, going forward. Can you get our mind around it, your hands? Really? It’s beyond my grasp.

They go on : “Progress Studies is closer to medicine than biology: The goal is to treat, not merely to understand.” Given their reach, if not their grasp, just what would treatment, the laying on of hands, entail? Read more »

Had enough of the 2020 election? Take heart, there are just 134 days left until Vote-If-You-Can Tuesday. That’s less time than it took Napoleon to march his Grande Armée into Russia, win several lightning victories, stall out, and then retreat through the brutal winter, with astronomical casualties, all the while inspiring the equally long War and Peace and the 1812 Overture.

Had enough of the 2020 election? Take heart, there are just 134 days left until Vote-If-You-Can Tuesday. That’s less time than it took Napoleon to march his Grande Armée into Russia, win several lightning victories, stall out, and then retreat through the brutal winter, with astronomical casualties, all the while inspiring the equally long War and Peace and the 1812 Overture.

Last time

Last time Philosophy’s original contrarian hero was, of course, Socrates. He believed in Truth and the Good and refused to back down from the pursuit of the these – even when his life was on the line. He had no patience for ‘just whatever people tend to say about such and such’. The unexamined life, for him, was not worth living. And that examination requires being ready to question even your most cherished beliefs.

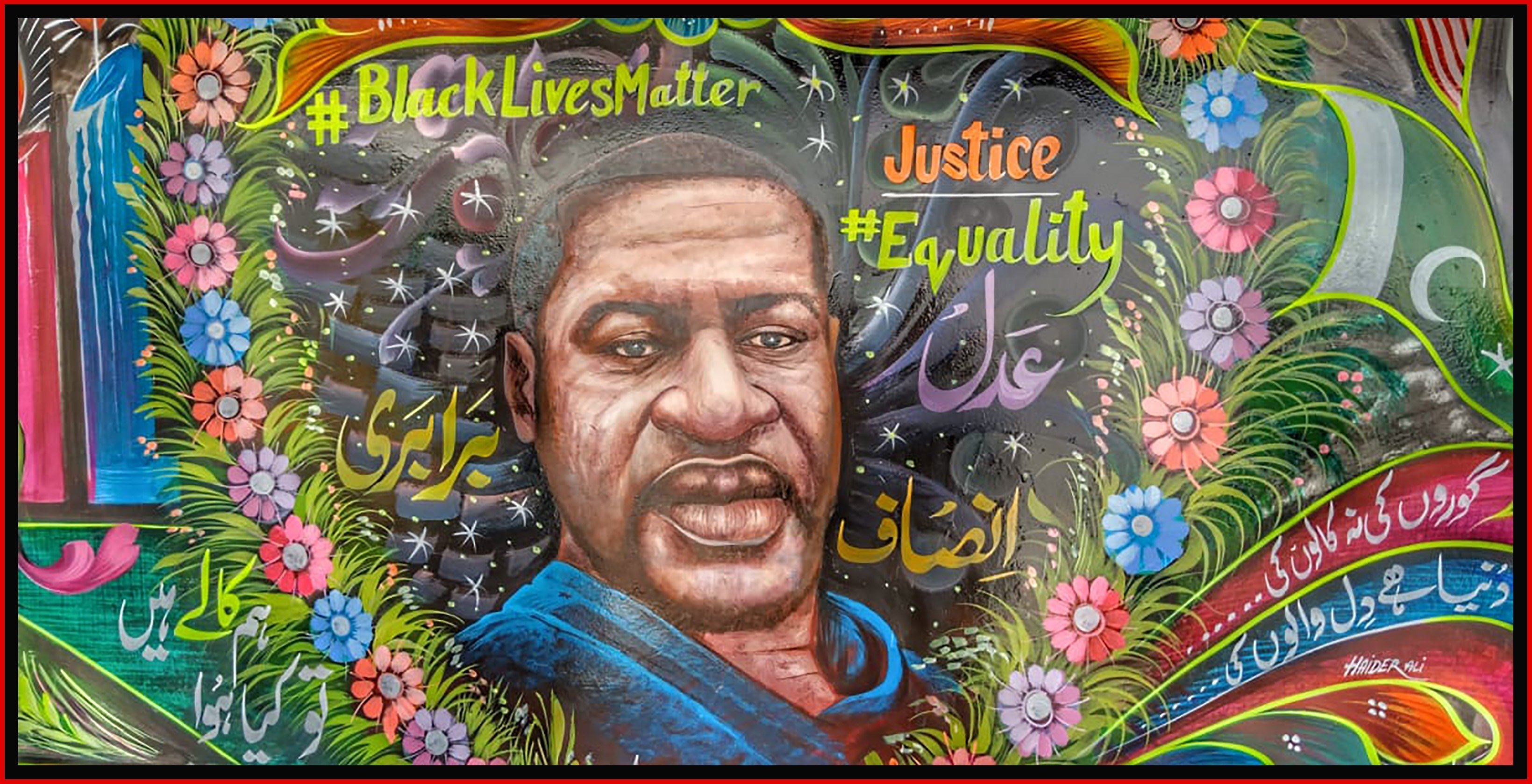

Philosophy’s original contrarian hero was, of course, Socrates. He believed in Truth and the Good and refused to back down from the pursuit of the these – even when his life was on the line. He had no patience for ‘just whatever people tend to say about such and such’. The unexamined life, for him, was not worth living. And that examination requires being ready to question even your most cherished beliefs. Some police officers are not above bad behavior, even as they work to eradicate and punish it in civilians. It is painfully clear that some of this bad behavior amounts to murder. Civilian review boards are a tool that could punish and deter police misconduct, but they need to have the ability to carry out independent investigations, subpoena documents and witnesses, and issue binding recommendations for discipline. As of a few years ago, only five of the top 50 largest police departments in the U.S. had civilian review boards with disciplinary authority. Newark, New Jersey has recently established such a review board after decades of efforts. While many activists have lost faith in civilian review boards, ACLU director of justice Udi Ofer argues that many of these boards were “rigged to fail.” He says a weak civilian review board is arguably worse than none at all, because it “can lead to an increase in community resentment, as residents go to the board to seek redress yet end up with little.”

Some police officers are not above bad behavior, even as they work to eradicate and punish it in civilians. It is painfully clear that some of this bad behavior amounts to murder. Civilian review boards are a tool that could punish and deter police misconduct, but they need to have the ability to carry out independent investigations, subpoena documents and witnesses, and issue binding recommendations for discipline. As of a few years ago, only five of the top 50 largest police departments in the U.S. had civilian review boards with disciplinary authority. Newark, New Jersey has recently established such a review board after decades of efforts. While many activists have lost faith in civilian review boards, ACLU director of justice Udi Ofer argues that many of these boards were “rigged to fail.” He says a weak civilian review board is arguably worse than none at all, because it “can lead to an increase in community resentment, as residents go to the board to seek redress yet end up with little.”

Now that we are witnessing a world that has withdrawn indoors, many people are reading plague literature, discussing Camus and Defoe, and reflecting on the nature of fear and contagion. But there is another kind of literature that lies neglected: stories that reflect the disconnect and dejection of seclusion -the literature of women’s isolation.

Now that we are witnessing a world that has withdrawn indoors, many people are reading plague literature, discussing Camus and Defoe, and reflecting on the nature of fear and contagion. But there is another kind of literature that lies neglected: stories that reflect the disconnect and dejection of seclusion -the literature of women’s isolation. When academics and journalists criticise technology today, they often assume the perspective of a bitter and desperate lover: intimately acquainted with the failings of technology, and vocal in pointing them out, but also too invested and unable to perceive the world without it.

When academics and journalists criticise technology today, they often assume the perspective of a bitter and desperate lover: intimately acquainted with the failings of technology, and vocal in pointing them out, but also too invested and unable to perceive the world without it.

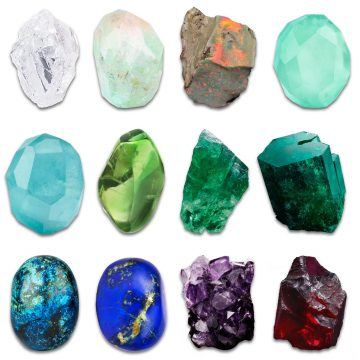

Gems carry a lure that is quintessentially primeval. Considered valuable throughout human history for obvious reasons such as rarity, durability and beauty, gems are inextricable not only from lore, art, architecture, culture, and craft, but also the aesthetics of language. Stories of different civilizations come to us carved in gemstones— Jade figurines of the Forbidden City in Beijing, lapis funerary masks of ancient Egypt, amber encrusted palaces in Moscow, the fabled and famously fought over “koh-i-noor” diamond, the emerald cups and diamond candlesticks of the Ottomans, the bejeweled “peacock throne,” the rubies of Ceylon— and stories manifold to these in words, from myths passed down via the oral tradition, to scripture, fairy tales, poetry and actual accounts of history, to science talk of archeology and gemology.

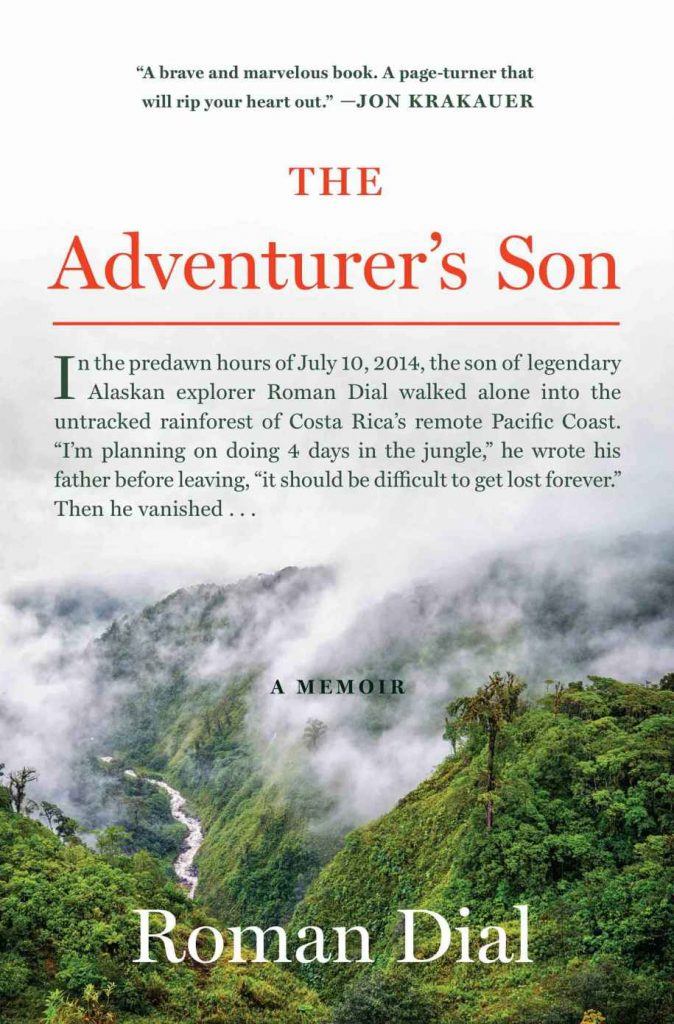

Gems carry a lure that is quintessentially primeval. Considered valuable throughout human history for obvious reasons such as rarity, durability and beauty, gems are inextricable not only from lore, art, architecture, culture, and craft, but also the aesthetics of language. Stories of different civilizations come to us carved in gemstones— Jade figurines of the Forbidden City in Beijing, lapis funerary masks of ancient Egypt, amber encrusted palaces in Moscow, the fabled and famously fought over “koh-i-noor” diamond, the emerald cups and diamond candlesticks of the Ottomans, the bejeweled “peacock throne,” the rubies of Ceylon— and stories manifold to these in words, from myths passed down via the oral tradition, to scripture, fairy tales, poetry and actual accounts of history, to science talk of archeology and gemology. Roman Dial has written a great tribute to his son, indeed to his entire family, in his book The Adventurer’s Son. An adventurer and biologist, Dial writes movingly of his relationship with his only son, Cody Roman Dial in particular and of his accidental death while exploring the rainforests of Central America. Dial’s pride in his son and the pain and grief over his loss are palpable throughout the book. But as Dial himself acknowledges, ‘we never know the future’, and the death of his son at just 27 years old in 2014 is an event he could never have imagined when he began to introduce him to the joys and challenges of exploring the natural world.

Roman Dial has written a great tribute to his son, indeed to his entire family, in his book The Adventurer’s Son. An adventurer and biologist, Dial writes movingly of his relationship with his only son, Cody Roman Dial in particular and of his accidental death while exploring the rainforests of Central America. Dial’s pride in his son and the pain and grief over his loss are palpable throughout the book. But as Dial himself acknowledges, ‘we never know the future’, and the death of his son at just 27 years old in 2014 is an event he could never have imagined when he began to introduce him to the joys and challenges of exploring the natural world. In coping with the dire economic crisis in the wake of the pandemic many developing countries have resorted to cash assistance to the poor for immediate relief. Beyond the relief aspect, many macro-economists have also pointed to the need for such programs to boost mass consumer demand in a period of one of the deepest slumps of general economic activity in many decades. As I have been an advocate for universal basic income (UBI) in poor countries for more than a decade now—my first published paper on the subject came out in India in March 2011 in the Economic and Political Weekly— I have often been asked if the widespread adoption of such cash assistance programs indicates that it is now a propitious time for UBI. While I have supported the cash relief programs in the context of the crisis (most of these programs have not been universal, mainly targeted to the poor) and consider the experience gained in this as generally useful, I think those who like me have supported UBI have usually thought about it in a longer-time framework and in the context of a more ‘normal’ state of the economy with appropriate institutions, political support base, and administrative structures in place. Of course, I’ll not object if in a post-pandemic world attempts are made to help the temporary crisis programs ultimately extend or evolve into a more general UBI program in poor countries.

In coping with the dire economic crisis in the wake of the pandemic many developing countries have resorted to cash assistance to the poor for immediate relief. Beyond the relief aspect, many macro-economists have also pointed to the need for such programs to boost mass consumer demand in a period of one of the deepest slumps of general economic activity in many decades. As I have been an advocate for universal basic income (UBI) in poor countries for more than a decade now—my first published paper on the subject came out in India in March 2011 in the Economic and Political Weekly— I have often been asked if the widespread adoption of such cash assistance programs indicates that it is now a propitious time for UBI. While I have supported the cash relief programs in the context of the crisis (most of these programs have not been universal, mainly targeted to the poor) and consider the experience gained in this as generally useful, I think those who like me have supported UBI have usually thought about it in a longer-time framework and in the context of a more ‘normal’ state of the economy with appropriate institutions, political support base, and administrative structures in place. Of course, I’ll not object if in a post-pandemic world attempts are made to help the temporary crisis programs ultimately extend or evolve into a more general UBI program in poor countries.