by Michael Liss

Put a small child in a room with a single marshmallow. Tell him that, if he can wait for five minutes, he gets a second one. Leave the room, and see what he does. Can he sit there, staring at that scrumptious-if-a-tad-rubbery mound of goo and powdered sugar and just fight off the urge to grab it, tear it to bits, and, like the Cheshire Cat, leave nothing but a smile?

Put a small child in a room with a single marshmallow. Tell him that, if he can wait for five minutes, he gets a second one. Leave the room, and see what he does. Can he sit there, staring at that scrumptious-if-a-tad-rubbery mound of goo and powdered sugar and just fight off the urge to grab it, tear it to bits, and, like the Cheshire Cat, leave nothing but a smile?

We, the voters, did it. We passed. Joe Biden will be our next President. America voted for stability and cohesiveness, for deferral of the pleasure of an adrenaline rush in return for a better outcome. We will, on January 20, 2021, be a better country for it.

We need to be better. Love him or loathe him, few could argue that President Trump was not a perpetual disrupter. Time may bring the perspective for more dispassionate analysis of his policies, but, right now, perhaps for just the next year or two, we need a different path.

There is an enemy at the gates we must confront and subdue. To do that, it’s increasingly clear we need an intense effort on the medical side, acceptance of public health measures, and system-wide cooperation. If we don’t get COVID-19 under control, we will not only let death walk amongst us unchallenged, but wreck our economy and our children’s future. Read more »

When we are done rhyming words of hope and history to audacity we will need to wake up. When the much needed elation and good cheer wears off, of getting job one done, defeating Trump then the reality will set in.

When we are done rhyming words of hope and history to audacity we will need to wake up. When the much needed elation and good cheer wears off, of getting job one done, defeating Trump then the reality will set in. think about that. Though others may have one, I lack an analytic framework. The best I can do is to offer some things I’ve been thinking about.

think about that. Though others may have one, I lack an analytic framework. The best I can do is to offer some things I’ve been thinking about.

I’ve been airborne since

I’ve been airborne since

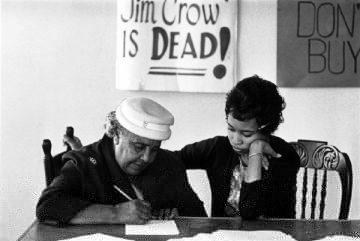

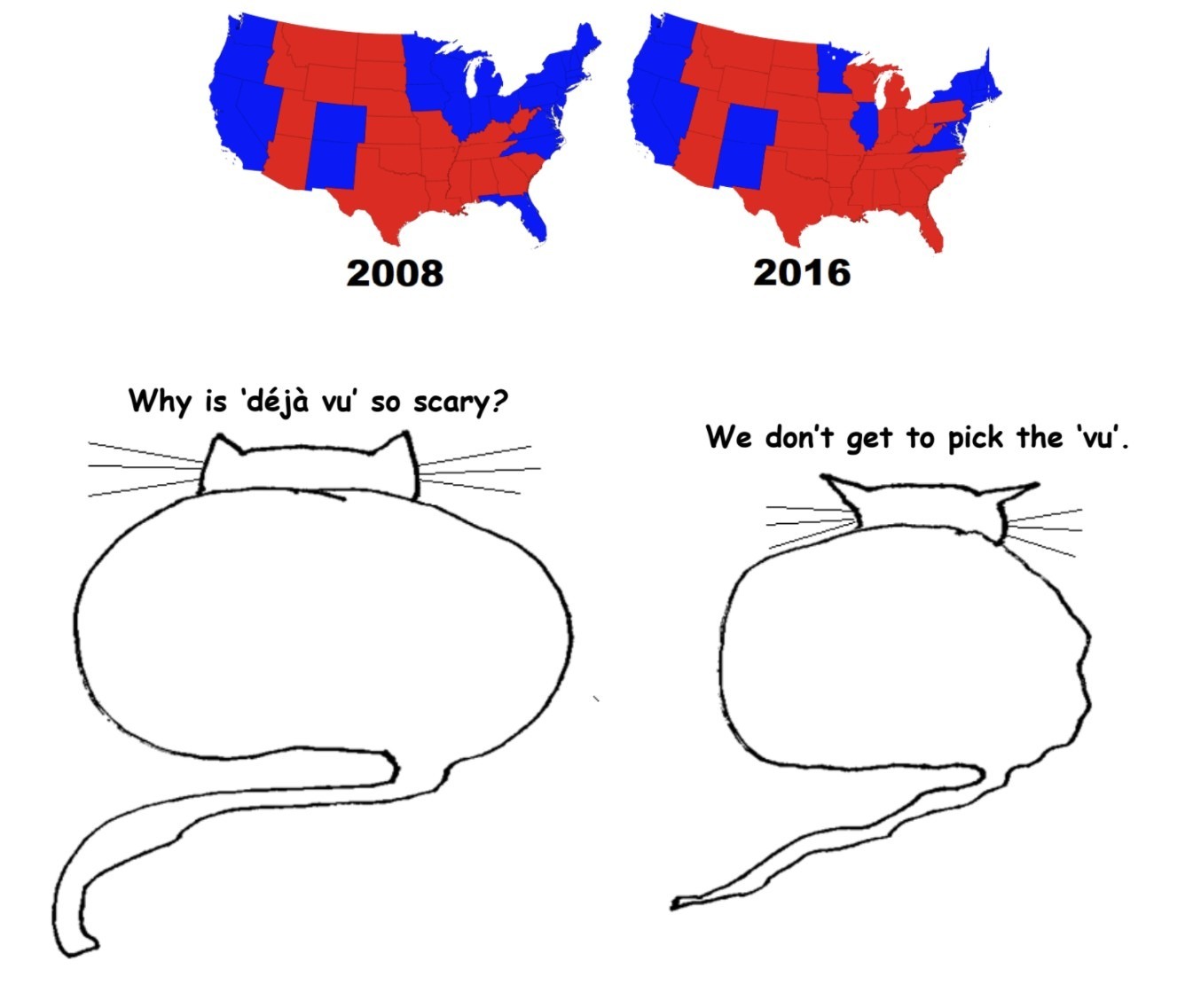

In the presidential election of 2016, around 45% of adult eligible to vote in the USA did not vote. It isn’t disputed that voter suppression, disproportionately affecting people of colour, was one of the causes. Another seems to be a cynicism, or apathy about the process itself. And there may be other reasons. But however you look at it, a situation in which nearly half of the eligible population doesn’t vote in an election for the highest office in the land ought to be causing a good deal of alarm, and not just for those political actors who reckon to be most damaged by this blank statistic. But then, ‘democracy’ has always been rather more of an unfulfilled promise than an accomplished fact, even in the Land of the Free (as well as in the land that boasts the ‘Mother of Parliaments’, where I live).

In the presidential election of 2016, around 45% of adult eligible to vote in the USA did not vote. It isn’t disputed that voter suppression, disproportionately affecting people of colour, was one of the causes. Another seems to be a cynicism, or apathy about the process itself. And there may be other reasons. But however you look at it, a situation in which nearly half of the eligible population doesn’t vote in an election for the highest office in the land ought to be causing a good deal of alarm, and not just for those political actors who reckon to be most damaged by this blank statistic. But then, ‘democracy’ has always been rather more of an unfulfilled promise than an accomplished fact, even in the Land of the Free (as well as in the land that boasts the ‘Mother of Parliaments’, where I live).

When I was a kid, I used to see this little sign everywhere (still see it occasionally): “No shoes. No shirt. No service.” It was on the door of every store, including the store down at the gas station. It used to make me laugh for some reason. Maybe, just the image of this shoeless, shirtless madman storming the store for more toilet paper.

When I was a kid, I used to see this little sign everywhere (still see it occasionally): “No shoes. No shirt. No service.” It was on the door of every store, including the store down at the gas station. It used to make me laugh for some reason. Maybe, just the image of this shoeless, shirtless madman storming the store for more toilet paper.

But Och! I backward cast my e’e,

But Och! I backward cast my e’e,

Bill: Can you believe these Republicans?! Just four years after swearing up and down that no nominee for the Supreme Court should ever be approved in an election year for the president, and promising on their mothers’ graves that they would never do such a thing, here they are doing exactly that!

Bill: Can you believe these Republicans?! Just four years after swearing up and down that no nominee for the Supreme Court should ever be approved in an election year for the president, and promising on their mothers’ graves that they would never do such a thing, here they are doing exactly that!