by Leanne Ogasawara

1. The philosopher and the translator

It was probably the most interesting translation job I ever had. Hired directly by the philosopher himself, my task was to translate into English a series of talks and papers he would be delivering in the US and Europe in the coming year. Philosophy being what I studied as an undergraduate, I had high hopes for the job. But my Japanese philosopher quickly became frustrated with me.

Leanne-san, is it possible for you to forget Descartes while you translate my papers? He wrote superciliously in a style of Japanese designed to be condescending beyond belief.

Well, this took me by surprise! Was it possible that I was guilty of an unconscious Cartesianism? Surely, he must be joking; for had I not studied at the feet of the great Heidegger scholar, Hubert Dreyfus, who had made it his mission to demolish Descartes in front of our very eyes –before turning to Heidegger? In all my philosophy classes, in fact, Descartes (always referred to as “the father of modern philosophy”) came up again and again–mainly in the form of other philosophers’ reactions to some aspect of his work.

So much so, that sometimes I think my understanding of Descartes is itself a rejection of Descartes.

And so, I informed my philosopher that not only had I forgotten Descartes long ago, but that I had no plans to ever remember him again.

He was not convinced and pressed his point.

His work, he explained, was in the field of “somaesthetics.” Specifically, he was writing on mind-body practices, like aikido and tea ceremony, which did not posit mind-body duality and indeed was premised on a kind of mind-body integration. And so, he was VERY BOTHERED by the way “dualism of the worst kind” ALWAYS crept into my translations. He called it a kind of “violence” (he used the English word here) on my part. It was at this point that I realized I was probably in over my head. For one thing, in English we need to join the two terms together to signify mind-body; while in Japanese so interconnected are the concepts for body and mind that the professor felt the need to use brackets to emphasize when he was strictly only referring to the physical (skeletal) body versus the entirety of the human being. The more I worked on this project, the more I realized the underlying differences in understanding; specifically that the Japanese notions were not premised on a picture of a human being as an encapsulated mind carried around within a body.

His work, he explained, was in the field of “somaesthetics.” Specifically, he was writing on mind-body practices, like aikido and tea ceremony, which did not posit mind-body duality and indeed was premised on a kind of mind-body integration. And so, he was VERY BOTHERED by the way “dualism of the worst kind” ALWAYS crept into my translations. He called it a kind of “violence” (he used the English word here) on my part. It was at this point that I realized I was probably in over my head. For one thing, in English we need to join the two terms together to signify mind-body; while in Japanese so interconnected are the concepts for body and mind that the professor felt the need to use brackets to emphasize when he was strictly only referring to the physical (skeletal) body versus the entirety of the human being. The more I worked on this project, the more I realized the underlying differences in understanding; specifically that the Japanese notions were not premised on a picture of a human being as an encapsulated mind carried around within a body.

2. Cogito ergo sum

Fast forward fifteen years, when recently I had the opportunity to revisit Descartes and his mind-body duality in a class held at the Huntington Library, in Pasadena. Taught by Descartes scholar Gideon Manning, we spent six weeks reading Descartes and having fruitful conversations about the philosopher’s work. Maybe Descartes is better read when one is in mid-life? Because I found Meditations to be much more appealing compared to when I first read the work thirty some years ago. Set out as a kind of intellectual “retreat,” Descartes first prepares a room where he will be able to think without disruptions. His aim? Well, it is nothing less than laying the epistemological groundwork for doing stable science. (Descartes was in today’s terms a mathematician and physicist first and foremost).

But how to clean the mind of all the dust that collects there?

I think it’s safe to say that as we get older, it is easy to allow bad mental habits to set in. Especially these days, when we are practically spoon-fed what to think by the media. Without deliberate free-range reading beyond our echo chambers and perhaps foreign travel to shake up our preconceived notions, we can without even realizing it, lose our ability for critical detachment. That is why in Meditation One, Descartes is directly challenging us to step back from the knowledge we take for granted. Not only is this a call to move outside our comfort zones, but it is a demand that we challenge each and every one of our notions to see what we are left with. Can anything certain be found to which we can build our understanding of the world?

In order to examine his beliefs and try and gain a critical distance from the standard models in philosophy and science of his time, Descartes utilized a form of radical doubt. Declaring that anything that can be doubted must be discounted, he thereby showed the unreliability of knowledge we derive from our senses. You’ve seen the Matrix, right? Even if you haven’t, you will probably agree that our senses are often misleading. For example, Descartes notes that our eyes will inform us that the sun and moon appear to be the same size in the sky. But we know that this is false. They are not the same size. And because we understand our senses to be unreliable, we can follow Descartes in concluding that we must find something better if we want to achieve a knowledge which is certain.

In order to examine his beliefs and try and gain a critical distance from the standard models in philosophy and science of his time, Descartes utilized a form of radical doubt. Declaring that anything that can be doubted must be discounted, he thereby showed the unreliability of knowledge we derive from our senses. You’ve seen the Matrix, right? Even if you haven’t, you will probably agree that our senses are often misleading. For example, Descartes notes that our eyes will inform us that the sun and moon appear to be the same size in the sky. But we know that this is false. They are not the same size. And because we understand our senses to be unreliable, we can follow Descartes in concluding that we must find something better if we want to achieve a knowledge which is certain.

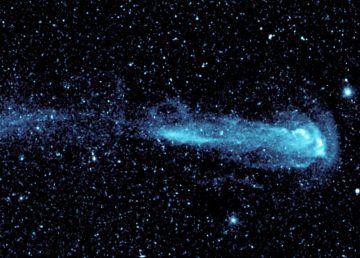

It bears mentioning that modern scientific instruments, like the telescope and the microscope, were not created in order to enhance or improve our senses but rather were created to bypass them. In order to access what cannot be seen by our human eyes, they seek to obtain truth vis-a-vis the world of mathematics. Think of how we understand colors. My husband’s research is all about trying to “see” what is, in fact, invisible to human eyes–the universe as appears in the ultraviolet spectrum. This is no longer a science of vision as it was before Descartes–but is a science of electromagnetic radiation –aka light.

After demolishing our sensory perceptions, Descartes continues in his radical doubting until almost nothing is left! Indeed, nothing is left as being certain except for the awareness he has of doubting things. All he can really know is that he is aware of thinking. He thereby arrives in Meditation Two to tell us that human beings are things that think. But here is where it gets strange. It is not that our bodies are doing the thinking– but rather something he calls “mind.” And this is how we arrive at an understanding of a human being as an insulated and encapsulated mind trapped within a body. According to Descartes, there are two distinct substances in the world: bodies, which obey the laws of physics and are mechanistic; and minds, which are non-physical and eternal.

And perhaps the kicker to this whole thing is that animals are not granted mind by Descartes, they are only soulless bodies.

3. A Romantic Reductionist

3. A Romantic Reductionist

In class last week, one of my fellow students remarked that in our age of biological materialism, Descartes’ understanding of “mind” is a bit hard to grasp.

I agree that there is much that is hard to swallow in Descartes–his proof for God for one thing. And as my class-mate suggested, so is Cartesian dualism.

But, the question of what is consciousness continues to trouble philosophers. And, not just philosophers. Scientists also tackle the problem of trying to reconcile a conscious mind with a physical brain. According to some, consciousness “emerges” from chemistry and electricity located in our brains. But how it arises –the mechanism– remains an unsolved problem. This as-yet unsolved mystery has led to two schools of thought. On the one hand we have the reductionists, who believe consciousness can be boiled down to molecules obeying scientific laws. And in the other camp we have the dualists (like Descartes in some very real ways), believing that consciousness cannot be explained by classical physics alone.

The other day, my husband told me very excitedly about a book written by a colleague of his neuroscientist Christof Koch. The book, called Consciousness: Conversations of a Romantic Reductionist, is wonderfully quirky, blending hard science and memoir. Calling himself a reductionist (and a “romantic” one at that), Koch tackles the question of “mind” in terms of physics, by trying to isolate the part of the brain responsible for consciousness in human beings. That’s right, he is looking for the physicality of consciousness. And this can be done, as one example, by performing EEG diagnostics on victims of brain injury to try and understand what kinds of brain trauma cause a loss in consciousness. Likewise, it can be done on people in deep sleep. Some questions immediately emerge:

How does anesthesia work? There are various anesthetic agents–but no common mechanism.

How about LSD? What does it tell us about consciousness?

Can free will be described as a kind of quantum superposition? Or is free-will an illusion?

Koch’s theory of consciousness builds on that of University of Wisconsin–Madison neuroscientist Giulio Tononi‘s integrated information theory (IIT), which posits that the degree of consciousness an organism experiences is a function of brain integration. Going back to the question concerning anesthesia, what appears to be disrupted by the various drugs is the large-scale functional integration in the corticothalamic complex (relating to the cerebral cortex and the thalamus). And this is also what happens to patients in a vegetative state. A person can experience brain trauma in various local areas of the brain and not lose consciousness (only capabilities). Complexity is necessary, but what really matters in terms of consciousness, Koch argues, is how interconnected and organized – how “integrated” – these neural circuits are. For example, computers are capable of storing much more memory than we are, but the information is not cross-referenced. As Koch explains it, his Mac, as yet, cannot recognize that various photos of his daughter at different stages of her life, from infancy to adulthood, are the same person; and not just the same person, but his beloved daughter. And this is because the data (or information) has not been integrated within the “brain” of the computer. (Think about Descartes’ wax argument).

Koch’s theory of consciousness builds on that of University of Wisconsin–Madison neuroscientist Giulio Tononi‘s integrated information theory (IIT), which posits that the degree of consciousness an organism experiences is a function of brain integration. Going back to the question concerning anesthesia, what appears to be disrupted by the various drugs is the large-scale functional integration in the corticothalamic complex (relating to the cerebral cortex and the thalamus). And this is also what happens to patients in a vegetative state. A person can experience brain trauma in various local areas of the brain and not lose consciousness (only capabilities). Complexity is necessary, but what really matters in terms of consciousness, Koch argues, is how interconnected and organized – how “integrated” – these neural circuits are. For example, computers are capable of storing much more memory than we are, but the information is not cross-referenced. As Koch explains it, his Mac, as yet, cannot recognize that various photos of his daughter at different stages of her life, from infancy to adulthood, are the same person; and not just the same person, but his beloved daughter. And this is because the data (or information) has not been integrated within the “brain” of the computer. (Think about Descartes’ wax argument).

Maybe Koch is correct and this is the key to consciousness. But there are competing theories– for this problem is nowhere near being solved.

4. Strange Loops

4. Strange Loops

Remember Douglas Hofstadter’s classic book, Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid? When I was at university, I was enthralled by this book. So, I was delighted to discover he had a relatively recent book out on the nature of consciousness, called I Am a Strange Loop (2007). Like Koch, Hofstadter is a hard-nosed reductionist. However, Hofstadter takes a different approach, believing consciousness to be more of a mirage that the brain creates to better function in the world. Not unlike Daniel Dennett’s argument that likens the brain to a smartphone and consciousness to that of the screen, Hofstadter views the mind as the “interface” that bridges the brain and the world. To try and understand how this happens physically (since neither Dennett nor Hofstadter are speaking metaphorically), imagine setting up a webcam on your computer and then turning it in such a way that it to faces the computer screen directly. When you do this, you will almost immediately begin to see your computer screen re-imaged back on the screen. As the images are cycled around from webcam to screen and back again, you will see a tunnel of screens eventually giving rise to a patch of shimmering blue. Now tilt the camera. You will now see geometrical spirally shapes spinning. (Interestingly, such video feedback loops are very reminiscent of hallucinations one can see using LSD). According to Hofstadter, our eyes and other sense organs are like the video camera above, and we use images to form representations of the world “out there” in our brains.

Descartes also viewed the mind as being insulated from the world “out there” and believed that all we had at our disposal were representations derived from sense experience. This was why he was aiming to bypass the body’s eye to gain more direct knowledge vis-a-vis the eye of the mind. Some philosophers and critics complain that Hofstadter’s strange loops are a way to “explain away” consciousness, instead of explaining it. But he is happy to take that criticism–as he thinks this is how consciousness arises, as a feedback loop of sensory perception being turned inward onto itself. While calling consciousness a mirage, the phenomenon still ultimately boils down to classical physics.

Philosopher David Chalmers does not agree and calls the problem of mind, the “hard problem.” He says, even if scientists are able to “locate” where in the body “mind” can be found, the mechanism for how this is transposed into subjective experience will remain. This is to suggest something that is in some way the opposite of what the reductionists say since Chalmers is claiming that “mind” is not reducible to a sum of the brain’s parts. Rather, consciousness has more in common, suggests Chalmers, with other fundamental building blocks of nature–like time and space. An emergent phenomenon. And that is sounding a bit like being back down the Cartesian rabbit hole again. But not to fear. Because I have good news. “Progress” in this field has been made, since all of these thinkers above– from Koch and Chalmers to Hofstadter– believe that whatever consciousness is, animals share it with us. Though Hofstadter does say add that mosquitoes are a special case; since if they have a soul, it’s an evil soul so he feels safe to swat them!

++

Recommended:

Sean Carroll did a fantastic podcast interview with philosopher David Chalmers, in which they discuss why this remains the hard problem in philosophy of mind

Christof Koch’s Consciousness: Conversations of a Romantic Reductionist

Douglas Hofstadter’s Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid? & I Am A Strange Loop

Michael Pollen’s How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence (About mental ruts in old age)

Also:

Russell Shorto’s Descartes’ Bones

AC Grayling’s The Age of Genius: The Seventeenth Century and the Birth of the Modern Mind