Sughra Raza. Autumn Water. Chittenden, September 2020.

Sughra Raza. Autumn Water. Chittenden, September 2020.

Digital photograph.

Sughra Raza. Autumn Water. Chittenden, September 2020.

Sughra Raza. Autumn Water. Chittenden, September 2020.

Digital photograph.

by Mike O’Brien

This column is not about the American election. You’re welcome.

Instead, I want to write about evidence, justification, and risk. This is partly a response to very recent events, and partly a regurgitation of some ideas I ruminated on years ago.

First, the recent bits. I was listening to the Montreal branch of Canadian national radio, a lunchtime call-in show that was asking listeners about their views on restaurant re-openings. Covid infections have spiked in the last month in Quebec, hovering around 1000 new cases per day in a population of roughly 8 million. The provincial government imposed a one-month lockdown on October 1st, shutting bars, restaurants, and other businesses and public facilities, as well as banning private gatherings. This was originally imposed on the metropolitan areas of Montreal and Quebec City, deemed “red zones”, but this designation was soon applied to just about every urbanized area along the St Lawrence river corridor.

It was a reluctant, long-avoided (bars had been open since late June) bid to keep Covid transmission sufficiently controlled to allow schools to remain open. The centre-right CAQ (Coalition for the Future of Quebec) government is very much a pro-business party, led by an airline entrepreneur, and has been accused of insisting on continued in-person schooling because it allows parents to return to work. I don’t doubt that this was a factor in their calculation, though they may also genuinely believe in their public claims that a return to schooling is necessary for the mental health and educational progress of children. They went so far as to deny children the choice to continue remote schooling, except for rare medical exemptions. I think it’s rather short-sighted, given that children are already known to be spreaders of the disease (and potentially victims of long-term harm, even if they are asymptomatic when infected). Given that Covid is not going away anytime soon, and may be surpassed by even worse viruses in the future, I would have liked to see our government build and maintain remote-learning infrastructure, to allow a rapid shutdown whenever necessary. But I don’t run the government. I just complain about it on the internet. Read more »

by Mary Hrovat

Autumn is brilliant. One of the things I looked forward to when I moved to the Midwest from the desert southwest was the experience of a year with four seasons. I did not anticipate how very beautiful autumn could be, and even after 40 years in the Midwest, I can’t get enough of this season. I can’t spend enough time outside in the wonderfully crisp air, under the low-angle sunlight, stopping to drink in the deep burnished golds, the lemony yellows, the gloriously variegated reds and oranges.

Autumn is brilliant. One of the things I looked forward to when I moved to the Midwest from the desert southwest was the experience of a year with four seasons. I did not anticipate how very beautiful autumn could be, and even after 40 years in the Midwest, I can’t get enough of this season. I can’t spend enough time outside in the wonderfully crisp air, under the low-angle sunlight, stopping to drink in the deep burnished golds, the lemony yellows, the gloriously variegated reds and oranges.

It took me a while to start recognizing specific types of trees instead of seeing only a mass of color, and I’m still learning new ones. I didn’t know until recently, for example, that the leaves of pawpaw trees turn the color of the sun in a child’s drawing. The pawpaw trees in my neighbors’ yard briefly cast a warm glow through my bedroom window on sunny afternoons this time of year. The leaves of ginkgo trees turn a similar color that deepens slightly with time; two huge old trees on campus drop countless small golden fans over the ground. (We won’t talk about the smell.)

I realize I have a surprising number of memories specifically about falling and fallen leaves: noticing dry leaves scurrying down the sidewalk, driven by a frisky wind on a cool autumn evening; pausing to watch a single yellow leaf drift to a rain-wet brick sidewalk under tenuous November sunshine as I hurried to a physics lab; seeing the perfect circles of red leaves on the ground under small maple trees; finding, one morning on my way to work, that an oak tree had dropped seemingly all of its leaves overnight, covering the sidewalk with a rich ruby carpet for me to walk on. Late one overcast afternoon last year, the clouds lifted near the western horizon, just enough for the setting sun to illuminate a maple with leaves that ranged in color from green to orange to scarlet. It blazed like a torch against an iron-gray eastern sky. I used to think moments like these pull me out of everyday life, but now I think they re-enchant it. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Mindy Clegg

Rarely do presidential elections seem so consequential, but 2020 has us all in agreement that voting is critical this year. Many simply yearn for a return to “the normal” of the Obama era or the Clinton years. Is the normal of the 90s and 2000s far enough to really address our various existential crises? I argue no. It’s clear that whatever our political orientation, we’re all reeling from the ongoing pandemic (and the threat of more in the future), global economic precarity (from several decades of neo-liberal policies, exacerbated by the pandemic), the erosion of individual rights among those historically oppressed, the rise of the hard right and the terroristic threats they pose, some left-wing accelerationism on the left, as well as the looming existential crisis of climate change, among other things. A general consensus has emerged that the current administration made these issues worse.

With the exception of a few hardcore holdouts, many prominent members of the President’s own party have come to admit the administration’s failures to address the above issues. Yet the administration represents the logical conclusion of the rightward lurch of the Overton window advocated by the GOP for years now. A quick survey of American and global politics tell us that the post Cold War neoliberal solutions failed us all. As we stare into the void that is 2020, now seems the perfect time to reassess and reorient ourselves to push for a more productive mode of problem-solving from our governments. Although voting Democratic down your tickets could begin this process, a real shift to creating more responsive governance that puts citizens first for the country and world will need active engagement and large-scale collective problem solving based on scientific facts rather than ideology. It is helpful to know the roots of our current problem so I will focus on two byproducts of the Cold War itself: the rise of neoliberal economic structures and the culture wars, and how Republicans and Democrats reacted to both. Solving these problems will require a strong political will for a New Deal level intervention that both regulates the economy and offers protection of basic rights for all. Read more »

by Peter Wells

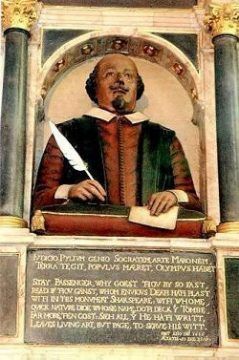

It’s dawned on me, looking at recent (and not so recent) commentary on Shakespeare, that a wedge is being driven between the Bard and the culture in which he lived. Although I haven’t actually heard the following syllogism, it seems to be lurking behind much current criticism:

It’s dawned on me, looking at recent (and not so recent) commentary on Shakespeare, that a wedge is being driven between the Bard and the culture in which he lived. Although I haven’t actually heard the following syllogism, it seems to be lurking behind much current criticism:

For example the explicitly Christian Sonnet 146 is variously dismissed as (a) uncharacteristic (b) insincere (c) the words of a ‘persona,’ or character, or (d) actually not Christian at all.

Whereas, personally, I think that a great deal of Shakespeare’s work can be better understood and appreciated, once we realise that it is grounded in the faith and beliefs of most of his fellow citizens, and that he took that faith seriously. We know that he used Biblical quotations and allusions frequently, they being the common language of his generation. But I would like to explore ways in which he might more meaningfully be described as a Christian. Read more »

Buddha died and

left behind a

big emptiness

— Allen Ginsberg

Vale of Kashmir

700,000 jackboots

fill the emptiness

— Rafiq Kathwari

by N. Gabriel Martin

Among the most frequent and important complaints against President Trump and his administration is that it has contributed to the degradation of public institutions. The title of an Op-Ed in The Atlantic this year referred to his “war on American institutions,” and even prior to his election an Op-Ed in The New York Times warned that he was targeting ‘democracy’s institutions’ with his threats to jail Hillary Clinton. It isn’t just political institutions that Trump undermines, as an article in Nature argued, but scientific institutions as well.

Neither is the threat facing institutions today limited to Trump; other Trump-like political figures, such as Boris Johnson, pose similar dangers, as an article in The New Statesman argued. Still, Trump epitomises it. To sloppily paraphrase Tolstoy: every bad president is bad in their own way. The epitome of George W. Bush’s badness was his futile and venal wars, Trump’s is his destruction of institutions.

As an indictment, the one levied against Trump is oddly intangible. It is surprising that the chief complaint against the most unpopular president in history is not about a death toll, unemployment figures, or some similarly hard fact. I don’t mean that it is less consequential or important, on the contrary, our ideas and other artifacts of our culture are immensely important, and it is encouraging to see broader recognition of their significance in the opposition to Trump. To many, including myself, Trump and his enablers have proven the importance of institutions that had previously escaped attention: institutions such as voting rights, an independent judiciary, and congressional oversight, to name just a few. By endangering these and others, Trump has brought our attention to things that are easy to overlook because of their intangibility and because they can be taken for granted as long as they are functioning normally. Read more »

by Fabio Tollon

COVID-19 has forced populations into lockdown, seen the restriction of rights, and caused widespread economic, social, and psychological harm. With only 11 countries having no confirmed cases of COVID-19 (as of this writing), we are globally beyond strategies that aim solely at containment. Most resources are now being directed at mitigation strategies. That is, strategies that aim to curtail how quickly the virus spreads. These strategies (such as physical and social distancing, increased hand-washing, mask-wearing, and proper respiratory etiquette) have been effective in delaying infection rates, and therefore reducing strain on healthcare workers and facilities. There has also been a wave of techno-solutionism (not unusual in times of crisis), which often comes with the unjustified belief that technological solutions provide the best (and sometimes only) ways to deal with the crisis in question.

Such perspectives, in the words of Michael Klenk, ask “what technology”, instead of asking “why technology”, and therefore run the risk of creating more problems than they solve. Klenk argues that such a focus is too narrow: it starts with the presumption that there should be technological solutions to our problems, and then stamps some ethics on afterwards to try and constrain problematic developments that may occur with the technology. This gets things exactly backwards. What we should instead be doing is asking whether we need a given technology, and then proceed from there. It is with this critical perspective in mind that I will investigate a new technological kid on the block: digital contact tracing. Basically, its implementation involves installing a smartphone app that, via Bluetooth, registers and stores the individual’s contacts. Should a user become infected, they can update their app with this information, which will then automatically ping all of their registered contacts. While much attention has been focused on privacy and trust concerns, this will not be my focus (see here for a good example of an analysis that looks specifically at these factors, drawn up by the team at Ethical Intelligence). I will instead focus on the question of whether digital contact tracing is fair. Read more »

by Thomas O’Dwyer

![Shakespeare & Company, Paris. [Wikipedia]](https://3quarksdaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/SandC.jpg)

Shakespeare and Company is still one of the world’s great bookstores. Its modern touristy ambience does it no favours, but its location in rue de la Bûcherie remains a Paris dreamscape, next to Place Saint-Michel, under the eternal gaze of Notre Dame across the Seine. While the store is a Mecca for book lovers, like other aspects of our angry and divided age, it has noisy detractors as well as champions. When the wandering American ex-serviceman Whitman renamed his existing bookshop Mistral as Shakespeare and Company in 1964, outraged literary purists considered it blatant commercial plagiarism. Sylvia Beach, who famously published James Joyce’s Ulysses when no one else would touch it, had founded her original Shakespeare and Company in 1919 and it remained a legend and writers’ haven at 12 rue de l’Odéon until German Nazi invaders forced its closure in 1941. Although Ernest Hemingway “liberated” it in 1945, Sylvia never reopened it. Read more »

by Callum Watts

Four years ago I looked at the US election and predicted that Donald Trump would likely win. The day after the election I described the kind of president he was likely to be. That he would ignore all norms, stack the federal judiciary and bureaucracy with lackeys who would obey him, and likely use private militias to intimidate political opponents. Many of these predictions have born true. A key part of my argument was trying to explain the sort of man Trump is, and therefore what his behaviours are likely to be, and what effect that was likely to have on the institutions he is in charge of. One of my main points was to stop imagining that shared norms in and of themselves can provide restraint to Trump’s power when he quite explicitly does not believe in them.

As we had towards November 3rd some new questions have appeared on the lips of many commentators, will Trump step down if he loses? And is the US on the verge of a coup? I don’t feel able to make any predictions this time around, but I do think there are some observations which are worth bearing in mind. On the issue of a coup we see some great journalists like Krystal Ball and Glenn Greenwald trying to resist the case that Trump is some kind of budding dictator or fascist. They worry that this kind of alarmism is exactly what drives cynicism in politics and voters into Trump’s embrace (I know, a horrible thought). And to some extent I agree; it doesn’t look like Trump operates according to anything like a coherent political programme or philosophy which can explain his behaviour and political machinations. However, I think these pundits are missing a key point. The key issue is not whether Trump is cut from the same cloth as other nationalist authoritarians and where he fits in this political taxonomy, it is understanding what Trump is likely to do, what he is able to do, and what he wants to do. Read more »

by Thomas R. Wells

Covid-19 reminds us once again that we can’t do without politics, or, to put it another way, we can’t do well without doing politics well.

‘Science’ can’t decide the right thing to do about Covid, however appealing it might be to imagine we could dump this whole mess on a bunch of epidemiologists in some ivory tower safely beyond the reach of grubby political bickering. This is not because scientists don’t know enough. The scientific understanding of Covid is a work in progress and hence uncertain and incomplete, but such imperfect knowledge can still be helpful. The reason is that since Covid became an epidemic it is no longer a merely scientific problem. Dealing with it requires balancing conflicting values and the interests of multitudes of people and organisations. This is an essentially political challenge that scientists lack the conceptual apparatus or legitimacy to address.

Epidemiologists can inform the political process but not replace it. In particular, they can advise governments on the sources of risk and the projected levels of risk associated with different Covid policies. However, as we have seen in the various approaches to lockdown and rollback around the world, how governments address Covid does not follow directly from their different epidemiological circumstances. Governments make two specific political choices well or badly: how much Covid risk to tolerate and how that risk ‘budget’ should be allocated between competing social needs and interest groups. Read more »

by Raji Jayaraman

Racial disparities are present in all aspects of life. In the U.S. labor market black men are 28 per cent less likely to be employed than white men, and those that are employed earn 69 cents on a white man’s dollar. Blacks and hispanics are 50 percent more likely to experience some kind of force in their interactions with police. Blacks drivers are 40 percent more likely to be stopped than white drivers. The prevalence of, and mortality from, Covid-19 is disproportionately high among blacks.

Racial disparities are present in all aspects of life. In the U.S. labor market black men are 28 per cent less likely to be employed than white men, and those that are employed earn 69 cents on a white man’s dollar. Blacks and hispanics are 50 percent more likely to experience some kind of force in their interactions with police. Blacks drivers are 40 percent more likely to be stopped than white drivers. The prevalence of, and mortality from, Covid-19 is disproportionately high among blacks.

Megan Thee Stallion’s opinion piece was one of last week’s most popular articles in the New York Times. In it, the hip-hop star notes that, “Maternal mortality rates for Black mothers are about three times higher than those for White mothers, an obvious sign of racial bias in health care.” What is obvious to me is that this disparity is unacceptable. What is less evident is that it is “an obvious sign of racial bias”. Is race per se to blame for racial disparities? Maybe, maybe not. It’s possible, perhaps even likely, that healthcare workers or employers harbour racial prejudice against blacks. But it’s not obvious and yet, this type of claim—that racial bias can be inferred from the presence of racial disparities—is commonplace.

Economists have an arguably simplistic, but nevertheless useful way to think about the question of racial disparity. They break it down into two categories: racial bias and statistical discrimination. Racial bias refers to plain vanilla “racism”—I treat a black person differently than I do a white person because I harbour racial prejudice against blacks. Statistical discrimination is at play when I treat blacks and whites differently because, quite apart from race, they have substantively different underlying characteristics. Read more »

maybe flower petals are held to stems by thought

and the wind’s a counter-thought that plucks

and sets them elsewhere in the grass

to grow in contemplative resolution

beside the notion of a grub-pulling crow

maybe the wind itself is a palpable bright idea,

something about motion and the abhorrence of vacuums

something about coming and going,

about ferocity and stillness

about war and its absence

maybe the moon’s the concept of fullness,

loss, abatement, regeneration from slivers,

hope at the hour of the wolf, the opposite of

darkness at the break of noon

maybe Descartes had it right

and this, from horizon to horizon, is

a simple ontology, an inherent daisy chain

of ideas chasing its tale —regardless,

……………….. one

…….. idea

hatched in this synapse nest

is to harvest

……………….. thought

from thought

under a

……………….. perception

of blue

while the

……………….. conception

of breeze

riffles the

……………….. hint

of hair

and I place them

like

……………….. dreams

of plums

into the

……………….. essence

of basket

and give them

with the

……………….. intention

of love

to my

……………….. belief

in the natural being

of

……………… you

Jim Culleny

2/26/11

by Emrys Westacott

Some people whose political views are liberal and progressive say they will not vote in the 2020 US election. They detest Donald Trump and his Republican enablers like senate leader Mitch McConnell; they oppose Trump’s policies on most issues–the environment, immigration, health care, voting rights, police brutality, gun control, etc.; but they still say they won’t vote. Why not?

Some people whose political views are liberal and progressive say they will not vote in the 2020 US election. They detest Donald Trump and his Republican enablers like senate leader Mitch McConnell; they oppose Trump’s policies on most issues–the environment, immigration, health care, voting rights, police brutality, gun control, etc.; but they still say they won’t vote. Why not?

One justification sometimes given for such a stance is: It has to get worse before it gets better. Yes, Trump and co are ruining much that is precious and causing a lot of suffering; but that is what has to happen to provoke revolutionary change. People will only be goaded into action when things become sufficiently dire.

To this, I have two responses. First, if you really believe that, then you should vote for Trump. If you want to see the country driven into a ditch, he’s clearly your man! Just look around. Why leave the job half done? Read more »

by Jackson Arn

Slurs have a way of mellowing into labels. History is full of Yankees and Cockneys, Methodists and Jesuits, Whigs and Tories, who steal a term of abuse and apply it to themselves as an act of sardonic revenge. Sometimes the tactic works too well, and people forget that the word was ever tainted. And sometimes the definition changes so many times people lose count, and the word is left to drag a muddle of meanings behind it.

“System” is such a word. Its DNA is full of recessive genes ready to reappear in the next generation. It suggests the banal and the sinister equally, a low, humming scientism and a hiss of danger. Politicians use it with both connotations in mind, sometimes both at once. Immigrants, trans activists, thwarted unionists are advised to have faith in the system, even as other politicians mock them for gaming it—can the two systems really be the same? Political science majors, not yet disillusioned, dream about the day they’ll change the system from within. In 1969, Bill Clinton, 23 years old and already impatiently waiting to be president, wrote, “I decided to accept the draft in spite of my beliefs for one reason: to maintain my political viability within the system.” Today, everyone seems to agree that the system, whatever it might be, is rigged. The word’s ambiguity is its longevity.

From the Greek: sun, meaning “with,” and histanal, meaning “set up, stand”—thus, a whole made out of parts, standing together. Which parts, and why they stand together, is left unclear—an ambiguity the rest of the sentence is supposed to correct but rarely does. This ambiguity is a part of the modern condition, since modernity depends on systems. Systems, rather than deities or monarchs, keep us safe: systems, for which individual parts are important but never all-important; systems, whose purpose, by definition, cannot be found in any single one of these parts.

Modernity is supposed to be an age of science, and the recent history of science is largely a history of systems. The word is already there, waiting for someone to connect the pieces: 1543, the solar system; 1628, the circulatory system; 1900, the nervous system; 1902, the endocrine system; 1956, the earliest mention of computer systems. In 1962, a NASA technician became the first person to say, “All systems go,” which isn’t a bad description of modernity itself. Read more »

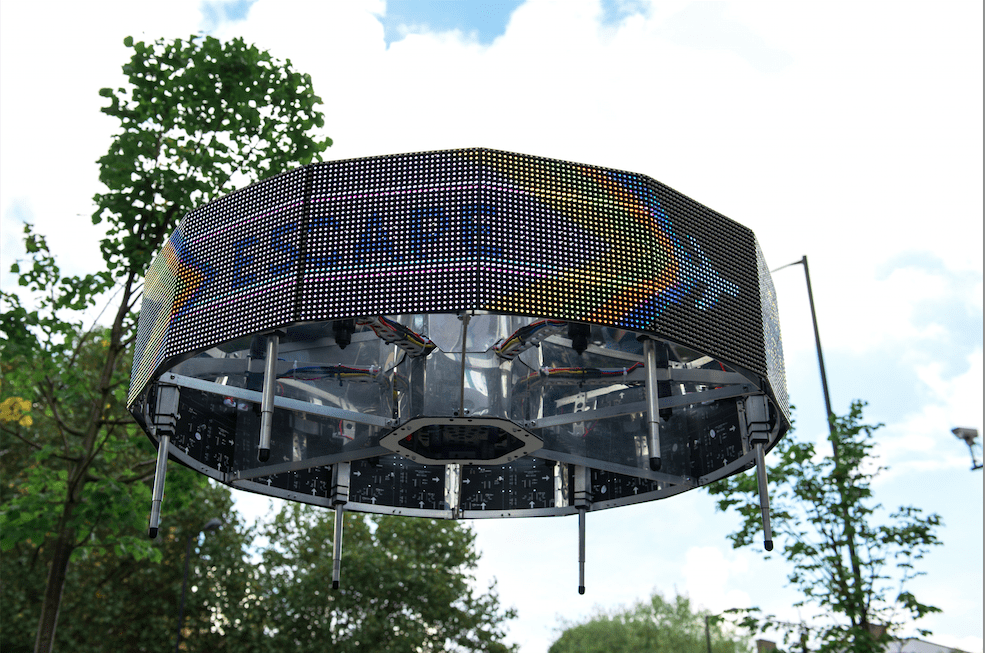

Anab Jain & Superflux. The Madison Flying Billboard Drone, 2015.

” … So there are five drones, and each of these drones is designed to embody specific tasks and functions that are already gaining popularity. We are not trying to imagine new roles for drones; we are trying to build them as consumer products. The aesthetic we’ve chosen is not a hacked DIY aesthetic, but instead a carefully designed consumer product aesthetic.

Madison, the flying billboard or the advertising drone, is a hovering display platform; it uses sophisticated facial recognition to cater advertising to the interests of those that it’s around. And companies could probably hire it, and have it beam its advertisements out to people, by farming all potential data from all these potential consumers.”

by Eric Miller

1.

A robin in the floating height of a pine warbled its fat phrases of three and, with its chest matching the tint of twilight clouds and light on leaves and houses—a lucent, resinous colour such as collected at the lower tip of every cone—, it seemed at once the motivation and the record of the fall of night.

Cartwheeling girls were to be expected. I knew, as one of the few boys in the neighbourhood, girls are more athletic than boys. They spun across the thick grass, not all grass, not meticulously kept; they spun beneath the widow’s white pine, she did not mind all the kids on her grass or depending like apes from her tree. A scent of crushed stems (in equal parts acrid and balmy), the clover-like odour of sweat in hair, made the affinity of plants and us amenable of olfactory proof.

The hill behind the widow’s house, pressing a slow muzzle to its foundation, distorted the building’s shape amiably—amiably, that is, to outward inspection. There must have been interior cracks and derangements. I have no evidence. I never went into it, only looking at it from the porch, or aslant from a higher elevation than the wrested roof. The widow had red hair, redder at dusk.

One girl especially was a virtuoso of jumping rope. She sang out the lyric that helped coordinate her steps; she might have been a sword-dancer, she was so agile; I listened for how her confident rendition of the rhyme became intermitted with gasps as, her pace not slacking, her smile brightening while she held it, her eyes contemptuous of any downward glance, her exertion made her fetch air harder into her lungs. The lyric went, Or-di-na-ry sec-re-ta-ry. Here was nothing ordinary, I would be happy to be its secretary: which has the word “secret” bosomed in it. Besides, I knew that secretaries were among the kindest people in the world. Read more »

by Jochen Szangolies

I want you to take a moment to reflect on the answer that first came to mind upon reading this question. Was it something related to your job? Are you a baker, a writer, a physicist, a construction worker? Or did you start thinking about your passions—the things you love, the things that drive and inspire you? Perhaps you define yourself by your values: you are who you are, because of what you hold right and good.

Identity has become a central, and somewhat fraught, topic in contemporary discourse. I believe that, in itself, is a sign of progress: in earlier times, identity was not something that was up for discussion; by and large, what made you you was decided by circumstances of your birth. You were born either noble, or a commoner; male or female; free or in bondage—and whichever of those buckets happenstance chose to place you in, would be the central driving force of your fortune. That today, we can worry about, struggle with, and redefine our identities is a sign of increasing self-determination—who we are is no longer just who we were born to be, but a matter of discovery and deliberation. Read more »