by Robyn Repko Waller

As the fall term winds down for universities across the US (and abroad), what has one semester, interrupted, and another one, planned, under COVID taught us about university life?

In March 2020, with the growing community spread of COVID-19 upon the nation, universities shuttered in response to the seismic early rumblings of the pandemic. Starting on the West Coast, institutions such as University of Washington and Stanford closed their campuses, suspending in-person teaching and activities, a trend that would quickly reach institutions of higher learning across the nation all the way to the eastern shores of the US.

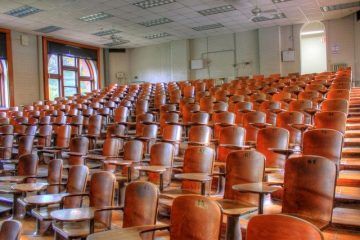

Empty lecture halls and dormitories — at least in term time — are a rarity. Lecture halls, laboratories, and dormitories of universities are meant to ring and echo with the hustle and bustle of human interaction. Gilbert Ryle, in his well-known explication of ‘category mistake’ in The Concept of the Mind gave this imagined (mis)description of the University:

A foreigner visiting Oxford or Cambridge for the first time is shown a number of colleges, libraries, playing fields, museums, scientific departments and administrative offices. He then asks ‘But where is the University? I have seen the where the members of the Colleges live, where the Registrar works, where the scientists experiment and the rest. But I have not yet seen the University in which reside and work the members of your University.’

Ryle’s aim was to illustrate that if one thinks, as the hypothetical visitor does, of the University as another member of the class of items which contains these buildings and locales, one has misunderstood what kind of thing the University is. One has seen the University already. But, I want to suggest, the COVID pandemic teaches us that neither the visitor nor Ryle even is entirely correct about the nature of the University. Visit the deserted campus structures and quad, vacated in response to COVID, and one has not really seen the University. Rather, the University is constituted by its human constituents, past and present — the academic community.

But where is the University — the academic community — now? And what is the academic community now? Read more »

1.

1.

Look on the back label of most wine bottles and you will find a tasting note that reads like a fruit basket—a list of various fruit aromas along with a few herb and oak-derived aromas that consumers are likely to find with some more or less dedicated sniffing. You will find a more extensive list of aromas if you visit the winery’s website and find the winemaker’s notes or read wine reviews published in wine magazines or online.

Look on the back label of most wine bottles and you will find a tasting note that reads like a fruit basket—a list of various fruit aromas along with a few herb and oak-derived aromas that consumers are likely to find with some more or less dedicated sniffing. You will find a more extensive list of aromas if you visit the winery’s website and find the winemaker’s notes or read wine reviews published in wine magazines or online. In a recent article in

In a recent article in  High in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta of northern Colombia, the Kogi people peaceably live and farm. Having isolated themselves in nearly inaccessible mountain hamlets for five hundred years, the Kogi retain the dubious distinction of being the only intact, pre-Columbian civilization in South America. As such, they are also rare representatives of a sustainable farming way of life that persists until the modern era. Yet, more than four decades ago, even they noticed that their highland climate was changing. The trees and grasses that grew around their mountain redoubt, the numbers and kinds of animals they saw, the sizes of lakes and glaciers, the flows of rivers—everything was changing. The Kogi, who refer to themselves as Elder Brother and understand themselves to be custodians of our planet, felt they must warn the world. So in the late 1980s, they sent an emissary to contact the documentary filmmaker, Alan Ereira of the BBC—one of the few people they’d previously met from the outside world. In the resulting film,

High in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta of northern Colombia, the Kogi people peaceably live and farm. Having isolated themselves in nearly inaccessible mountain hamlets for five hundred years, the Kogi retain the dubious distinction of being the only intact, pre-Columbian civilization in South America. As such, they are also rare representatives of a sustainable farming way of life that persists until the modern era. Yet, more than four decades ago, even they noticed that their highland climate was changing. The trees and grasses that grew around their mountain redoubt, the numbers and kinds of animals they saw, the sizes of lakes and glaciers, the flows of rivers—everything was changing. The Kogi, who refer to themselves as Elder Brother and understand themselves to be custodians of our planet, felt they must warn the world. So in the late 1980s, they sent an emissary to contact the documentary filmmaker, Alan Ereira of the BBC—one of the few people they’d previously met from the outside world. In the resulting film,

People are basically good.

People are basically good. Here’s an interesting game. You receive 20 dollars, and you and three others can anonymously contribute any portion of this amount to a public pool. The amount of money in this pool is then multiplied by 1.5 and divided equally among all players. Repeat 10 times, then go home with your money. What will happen? How much would you contribute in round one, if you knew nothing about your fellow players?

Here’s an interesting game. You receive 20 dollars, and you and three others can anonymously contribute any portion of this amount to a public pool. The amount of money in this pool is then multiplied by 1.5 and divided equally among all players. Repeat 10 times, then go home with your money. What will happen? How much would you contribute in round one, if you knew nothing about your fellow players?

Now that a deranged president’s toxic presence will finally—finally!—begin to occupy increasingly smaller tracts of our inner lives, these new days might offer an ideal occasion to celebrate songs that sing of the singular mental spaces hidden inside us all—songs that can help re-acquaint us with ourselves.

Now that a deranged president’s toxic presence will finally—finally!—begin to occupy increasingly smaller tracts of our inner lives, these new days might offer an ideal occasion to celebrate songs that sing of the singular mental spaces hidden inside us all—songs that can help re-acquaint us with ourselves.