by Usha Alexander

[This is the fourth in a series of essays, On Climate Truth and Fiction, in which I raise questions about environmental distress, the human experience, and storytelling. All the articles in this series can be read here.]

Tabea Bakeua lives in Kiribati, a North Pacific atoll nation. Her country is likely to be the first to disappear completely under the rising seas within a few decades. Asked by foreign documentary filmmakers if she “believes” in climate change, Bakeua considers and tells them, “I have seen climate change, the consequences of climate change. But I don’t believe it as a religious person. There’s a thing in the Bible, where they say that god sends this person to tell all the people that there will be no more floods. So I am still believing in that.” She smiles, self-consciously, as she continues. “And the reason why I am still believing in that is because I’m afraid. And I don’t know how to get all my fifty or sixty family members away from here.” She’s still smiling as tears fill her eyes. “That’s why I’m afraid. But I’m putting it behind me because I just don’t know what to do.” She turns, apologetically, to wipe away her tears. [from “The Tropical Paradise Being Swallowed By The Pacific” by Journeyman Pictures]

Tabea Bakeua lives in Kiribati, a North Pacific atoll nation. Her country is likely to be the first to disappear completely under the rising seas within a few decades. Asked by foreign documentary filmmakers if she “believes” in climate change, Bakeua considers and tells them, “I have seen climate change, the consequences of climate change. But I don’t believe it as a religious person. There’s a thing in the Bible, where they say that god sends this person to tell all the people that there will be no more floods. So I am still believing in that.” She smiles, self-consciously, as she continues. “And the reason why I am still believing in that is because I’m afraid. And I don’t know how to get all my fifty or sixty family members away from here.” She’s still smiling as tears fill her eyes. “That’s why I’m afraid. But I’m putting it behind me because I just don’t know what to do.” She turns, apologetically, to wipe away her tears. [from “The Tropical Paradise Being Swallowed By The Pacific” by Journeyman Pictures]

***

Bakeua’s response is one of many that people now have about anthropogenic climate change. Grasping for magic or miracles in the face of destruction and helplessness, her narrative is common among her hundred thousand fellow citizens. Having remained self-sufficient and sustainably prosperous in their way of life for thousands of years—while contributing effectively zero carbon emissions—they will abruptly be left with nothing as the encroaching tides sweep their lands out from under them, sacrificing their islands for the greater prosperity of other countries. The people of Kiribati played no part in triggering this annihilation and have no way of withstanding it. Nor is the international community throwing them a life raft—through compensatory rights to lands, housing, livelihoods, and autonomy, elsewhere, as would be just—nor even expressing any meaningful concern for their plight.

How did we get to this tragic moment? Read more »

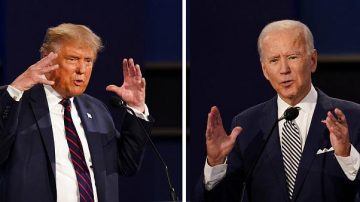

We live in The Year Of Overlapping Catastrophes. Oh 2020, we know ye all too well. The pandemic, our very own plague. Economic depression. A quasi-fascistic con man at the head of government. The discovery that perhaps forty percent of our fellow Americans are truth-hating dupes and low-information racists. (Brits too. Decline of the Anglophone empire?)

We live in The Year Of Overlapping Catastrophes. Oh 2020, we know ye all too well. The pandemic, our very own plague. Economic depression. A quasi-fascistic con man at the head of government. The discovery that perhaps forty percent of our fellow Americans are truth-hating dupes and low-information racists. (Brits too. Decline of the Anglophone empire?)

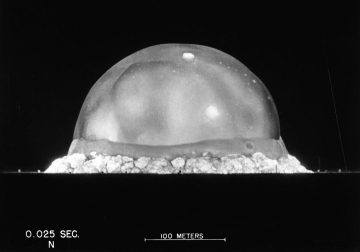

There are times where we are simply unable to surpass our elders.

There are times where we are simply unable to surpass our elders.

A system update recently downloaded to my cellphone included artificial intelligence capable of facial recognition. I know this because, when I subsequently opened the “Gallery” function to send a photograph, I discovered that the refurbished app had taken it upon itself to create a new “album” (alongside “Camera”, “Downloads” and “Screenshots”) called “Stories”, within which I found assemblages of my own pictures, culled from all of those other albums and assorted thematically, evidently because they depicted identical, or similar, figures.

A system update recently downloaded to my cellphone included artificial intelligence capable of facial recognition. I know this because, when I subsequently opened the “Gallery” function to send a photograph, I discovered that the refurbished app had taken it upon itself to create a new “album” (alongside “Camera”, “Downloads” and “Screenshots”) called “Stories”, within which I found assemblages of my own pictures, culled from all of those other albums and assorted thematically, evidently because they depicted identical, or similar, figures. FRONT PORCH

FRONT PORCH

Is there anything more clichéd than some spoiled, petulant celebrity publicly threatening to move to Canada if the candidate they most despise wins an election? These tantrums have at least four problems:

Is there anything more clichéd than some spoiled, petulant celebrity publicly threatening to move to Canada if the candidate they most despise wins an election? These tantrums have at least four problems:

Last time, in

Last time, in

Sughra Raza. Lesser Weaver Nests, Akagera National Park, Rwanda. 2018.

Sughra Raza. Lesser Weaver Nests, Akagera National Park, Rwanda. 2018.