by David Oates

We live in The Year Of Overlapping Catastrophes. Oh 2020, we know ye all too well. The pandemic, our very own plague. Economic depression. A quasi-fascistic con man at the head of government. The discovery that perhaps forty percent of our fellow Americans are truth-hating dupes and low-information racists. (Brits too. Decline of the Anglophone empire?)

We live in The Year Of Overlapping Catastrophes. Oh 2020, we know ye all too well. The pandemic, our very own plague. Economic depression. A quasi-fascistic con man at the head of government. The discovery that perhaps forty percent of our fellow Americans are truth-hating dupes and low-information racists. (Brits too. Decline of the Anglophone empire?)

Oh, and behind all that: The overheating of the entire planet. Collapse of ecosystems. That slow-motion master-problem that too many of us have tried to keep from facing.

Reader, it’s too much to bear. So I’m going to sound one frail note – offer one flutelike moment of optimistic maybe-ing. I’m going to nominate our plague for a noble prize: The Plague That Saved The World.

* * *

Sometimes things are moving in the opposite direction than they seem to be.

Ancient astronomers knew that the planets sometimes appeared to be traveling backwards against the starry background. This “retrograde motion” caused no end of head-scratching and the invention of ingenious explanations and visualizations – little wheels within big ones, and so forth.

In the crazymaking experience of actually living through our moment of history, one of the reasons we never know for sure what’s happening is that outcomes are sometimes perversely ironic: i.e., the opposite of what one might have expected. Retrograde. Of course most of the time, awfulness follows awfulness, predictable suffering hard on the heels of ignorance and greed. Most of the time.

The exceptions are what drive us mad with maybeing, with hoping against hope. History is studded with oddly salubrious side-effects to truly awful happenings. For instance, The Renaissance (worthy of a cap on the article surely), seems to have entirely ironic parentage. The fall of Constantinople in 1453? Terrible. But… to escape the Ottomans, classical scholars scurried off to Italy carrying armloads of ancient Greek and Latin texts. And suddenly Italy is rereading its past. . . and producing the present. Our present.

As a tool for thinking about history’s strange affinity for linking dire events with lucky outcomes, Barbara Tuchman’s book about the 1300s in Europe is unmatched. This is the century preceding The Renaissance of course. Its incubation. And Tuchman’s steely-eyed account of that century of ignorant piety and clueless monarchs and vainglorious nobles clashing in fields of mud – while The Black Death kills off half or a third of the population – seems indeed to be a master course in human nature and the meaning of history. (The meaning being, don’t expect it to make sense.)

But yet the takeaway from this course in reality is how it all conspired to produce The Renaissance. Humanism. Michelangelo’s David. Science. Galileo. The Sistine Chapel. Indeed, “the Black Death may have been the unrecognized beginning of modern man.” Really, Tuchman’s book is worth a read just for that.

Long ago I read a remark by a historian which perfectly framed up the real payoff for the study of history: “What’s important in the study of history is not remembering all the details of what happened, but developing a sense of how things happen.” (This is a paraphrase, from a source whose identity I can no longer remember.) The point goes deep into our understanding not just of the past, but of the present. No one with a sense of history will be surprised when goof-ups and incompetence produce disasters. It’s the way things happen. It’s normal. Which means also that the historically-informed won’t be tempted to explain our goofed-up human affairs as products of vast, secret cabals of unbelievable potency (and invisibility). It’s just not the way things happen.

From the death and disquiet of the 1300s arose surprising movements in freedom, even before The Renaissance. Peasants (or “villeins”) were loosed from near-serfdom by the simple fact of labor shortage following bubonic die-off. Unhappy workers had simply to leave their masters’ tools in the field and hit the road, to be welcomed by landowners in the next county desperate to get the crops in. And these radically shifting economic realities produced some astonishingly egalitarian thinking. Check out English peasant-revolt leader Wat Tyler’s demands, made directly to the face of an astonished Richard II: levelling of all distinctions below that of King; democratic redistribution of all lands and holdings of the church. A new day which Karl Marx’s visions could hardly top.

Strange, even shocking advances, from dire causes. How about this one: Desperate to stem the Plague, officials had handbills of emergency regulations and warnings written up in the local language. Not in civilized Latin. Not in courtly French. No: in the Middle English of the peasants. And by century’s end the first written masterpiece of vernacular English appears, courtesy of Geoffrey Chaucer.

Leading me to this cheerful declaration: Some of what might eventuate from our current year of disease and governance-by-stupidity will be ironically surprising. Will be lucky advances snatched from the jaws of disaster.

It is, after all, one of the ways things happen.

* * *

Our current events already show signs of following this pattern of ironically beneficial side effects.

The African American political scientist Christopher Parker, confronted by the 2016 Republican campaign, saw opportunity in it. “The plain fact is that Trump’s racism is out in the open for all to see. This punctures the self-deceptive narrative that now defines racial discrimination in America, one that permits whites to explicitly deny the existence of racism while implicitly accepting and perpetuating it through the use of racialized code words….It’s not a stretch to say that Trump’s candidacy could even do more to advance racial understanding than the election of Barack Obama.”

When I asked Parker recently whether the intervening years of this presidency have validated his ironic hope, he affirmed it. “I was right. The increased support for BLM over what it was four years ago, and the sea of white faces during protests in support of BLM, support my claim.”

How things happen. There’s a nonlinear aspect to history. It’s part of what makes it terrifying (and occasionally exhilarating) to live through.

* * *

Commentators have started to notice that we’ve been launched into strange space by our overlapping difficulties. The evolving insight is – don’t expect things to “go back to normal.” The old world is gone. Our reality, and equally importantly our sense of reality, are changing. But to what?

Nicolas Kristoff, writing in the New York Times, thinks that the scale of our difficulties gives us “a chance for a reset.” He lists the coronavirus plague, the economic slump, the newly energized activism for racial justice – and invokes the analogy of the Great Depression. “In the 1930s the unequivocal nature of Hoover’s failures helped win Roosevelt his mandate and made the New Deal possible. Maybe national anguish can again be the midwife of progress.” He quotes business, social, and political leaders who sense the opportunities opened by our struggles, from pols and ex-presidents (Cory Booker, Jimmy Carter) to heads of socially conscious change agents (Marion Wright Edelman of the Children’s Defense Fund; Darren Walker of the Ford Foundation).

Interestingly, Kristoff scarcely notices the climate-change challenge that hovers menacingly behind the huge but temporary distresses of virus and economic slowdown. It’s an omission we must fill in.

Ross Douthat, Kristoff’s colleague at the Times, spins the moment differently, but he too sees that our mounting difficulties have changed the trajectory of history – by accelerating it. “Trends that were working slowly have seemingly speeded up. . . . The pandemic has put history on fast-forward.” The world we might have expected to see in, oh say 2030, will be showing up much sooner. When we wake from our viral and economic torpors, the future will be already here. As a conservative, however, he seems more worried than encouraged by rapid change. He fears consolidations of power and “growing ideological conformity” in liberal (or what I would call “egalitarian”) directions. Rather than noticing opportunities to address longstanding evils of entrenched injustice and stagnant wealth-accumulation, he wrings his hands.

He too fails to notice the minor detail that the entire biophysical world is also in crisis.

* * *

Our cultural moment seethes with crisis and strange possibility. The deepest look into it that I know of – and the most hopeful – is found in a New Yorker article from last spring by science-fiction novelist Kim Stanley Robinson. He plunges right into the master-catastrophe of climate change that’s been ignored under all this political hubbub.

Robinson proposes that we have been, for a few decades, “out of synch” with our biophysical realities. We have known about climate change, but we remain motionless, unable to act, “paralyzed.” It’s dreamlike, nightmare-like. Decades of this. Economies thriving as the world sickens and begins a piecemeal death. The rich enriching themselves, as ordinary citizens fall ever further behind. And we watch, filled with dread. Stuck in old ways – individualism. Corporatism. Capitalism. The lie that money is the measure and limit of all things.

We have been “living in the world without feeling it.” That has been our strange half-life. What we know is real – the fearfully changing climate – has not been able to move us.

But Robinson sees that the plague has been teaching us otherwise. Suddenly, collectively, we have been learning in these plague months that science works; and that we can, and must, act in concert. We understand these facts in our rational minds, but we also experience them in our bodies and in social interactions with others. These insights are becoming new and vital structures of feeling.

Robinson says that the daily interactions (and deprivations) of the plague months have been our teachers:

Although we are practicing social distancing as we need to, we want to be social – we not only want to be social, we’ve got to be social, if we are to survive. It’s a new feeling, this alienation and solidarity at once. It’s the reality of the social; it’s seeing the tangible existence of a society of strangers, all of whom depend on one another to survive. It’s as if the reality of citizenship has smacked us in the face.

Under the conditions of plague, it has become vividly clear that denying and pretending are childish, if not idiotic. Certainly deadly. Airy positive-thinking and mystic god-bothering are equally exposed as dead ends, ineffective in the brute matter of staying alive and keeping your loved ones alive. It’s not a matter of “political perspective” or “religious choice” any more – it’s life or death. We see it now. It’s not really an argument. It’s obvious.

Now we know what “our scientific, educated, high-tech species is capable of doing.” And we have been feeling the reality of sacrificing in the present, so that the future – next year, next decade – will be better.

Daily and hourly, our experiences of adaptation, realism, and solidarity under plague conditions are preparing us for a dramatic pivot in our response to climate change. Robinson’s hopeful message is that we understand in a new and direct way. We’ve had practice now. We know what works. We grasp (in the gut as well as the mind) that present sacrifice, change, even disruption, may be necessary for long-term well being. And that science must guide us – evidence-based decision making, not political point-scoring.

The pandemic plague is our Constantinople burning. It seems terrible, and it is. But all the while, it is also equipping us for the even bigger fight against climate catastrophe. “The spring of 2020 is suggestive of how much, and how quickly we can change. It’s like a bell ringing to start a race. Off we go – into a new time.”

* * *

Reader, when we do finally go, when we finally take action, it will be shocking how much energy is unlocked from the paralysis of climate-change dread we have been living in. For decades this dread has been building. Now our collective avoidance has become like a task that has been put off and put off until it assumes, in the imagination, impossible dimensions. A monster in the closet.

When that morning of exasperated reckoning finally arrives and the boogieman is faced, it’s always surprising how much easier it is than the shadows and procrastination and denial had made it out to be. A matter of doing, instead of dithering.

The plague has shown us how, and shown us why too. We know that our fate is each other, and that all of us living creatures are entwined in a global heartbeat of atmosphere and current and climate. We know we must begin, now. The candidate has tempered his offerings, triangulated a position less forthright on climate, though undoubtedly one moving in the needed direction. Once in office, will he feel the ripeness of this moment too, and respond?

When we do begin, I predict this: We will be amazed at how much wholesome rolling-up-the-sleeves energy is available for the necessary tasks. How much good will, how much willingness to do the hard thing. Yes, and how much money we will find for it, too. Didn’t we materialize a trillion dollars, out of nothing but national will, for this disease and its economic collapse? And when we can say, “At last, we’re doing everything we can” – how great will be the heart, the solidarity, the grown-up joy of taking care of business.

Perhaps this beginning is just a few months away.

Perhaps this current president’s ridiculous and negligent handling of the Covid plague will tip the scales and we will choose a new president, willing and ready to act. And perhaps this plague will have shown us how to feel loyalty to each other and stand together. How to listen to the evidence. How to shoulder the hard tasks.

Perhaps this will be known in history-to-come as The Plague that Saved the World.

Things do sometimes happen that way.

SOURCES:

Barbara W. Tuchman, A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century (Ballantine, 1978).

Steve LeVine, “How the Black Death Radically Changed the Course of History: And what that can teach us about the coronavirus’ potential to do the same.” Medium 1 April 2020. https://gen.medium.com/how-the-black-death-radically-changed-the-course-of-history-644386f5b803.

Christopher S. Parker, “Do Trump’s Racist Appeals Have a Silver Lining?” The American Prospect 19 May 2016.

Nicholas Kristof, “We Interrupt This Gloom to Offer. . . Hope.” New York Times 19 July 2020.

Ross Douthat, “Waking Up in 2030.” New York Times 28 June 2020.

Kim Stanley Robinson, “The Coronavirus Is Rewriting Our Imaginations.” The New Yorker 1 May 2020.

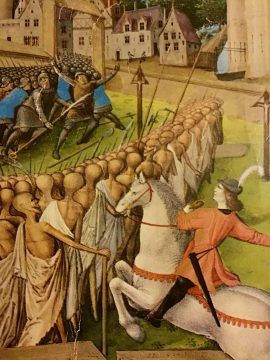

Illustration: “The fourth horseman of the apocalypse”(detail), Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry. From cover, Barbara W. Tuchman, A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century (Ballantine, 1978). Photo David Oates.