by Angela Starita

Over the past six years, I’ve intermittently studied weaving. For reasons unknown to me, I’ve wanted to weave for at least the last 20 years, but only as a distant dream. It was part of a larger fantasy, one I wrote an essay about years ago: riding a bike to a clean studio reminiscent of a kindergarten classroom, lots of light, plywood furniture and reams of color in the form of signage and yarn and material. I’d go there every day, work on a project and other women would be working on their projects–parallel experiences but no collaboration. There would be long periods of quiet as we concentrated with occasional meal breaks. By 3 or 4, we might start talking, playing music, showing off our progress. Then we’d clean up our spaces and bike back home. This was how we’d make our living. The specifics of our funding sources remained unresolved —it was a daydream, and I had enough trouble figuring out money flow in real life.

The essay, though, was really about my ambivalence towards fiber art, something I didn’t sense in the younger women who were taking up knitting and crocheting and sewing with what I deemed nary a moment of critical reflection about the historic role of those skills in women’s lives. In articles at the time, needle arts were seen as part of a DIY trend, a resurrection of skills learned from grandmothers and with a fair amount of attendant nostalgia. Both my grandmothers were talented at knitting and sewing, and in fact, I learned the basics of crochet from one of them. The other was in a deep senility by the time I was born, but I learned that she’d been hesitant to teach those skills to her three daughters. Her mantra was go to college and get a good job so you stay in a marriage because you want to, not because you have to.

Though I think her own marriage was a strong one, my grandfather’s insolvency in the middle of the Depression meant she needed to go back to freelance garment work. She’d spend whole nights bent over a crochet beading loom, prepping beads that she’d sew onto evening gowns for a designer she called Miss Ania. Those weren’t skills she wanted her girls to depend on. Read more »

Junya Ishigami. Serpentine Gallery Pavilion, 2019.

Junya Ishigami. Serpentine Gallery Pavilion, 2019.

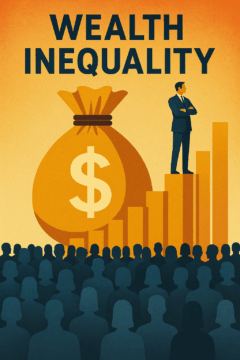

By many measures wealth inequality in the US and globally has increased significantly over the last several decades. The number of billionaires has increased at a staggering rate. Since 1987, Forbes has systematically verified and counted the global number of billionaires. In 1987, Forbes counted 140. Two decades later Forbes tallied a little over 1000. It counted 2000 billionaires in 2017. In 2024 it counted 2,781, and in March this year it counted 3,028 billionaires (a 50% increase in the number of billionaires since 2017 and almost a 9% increase since 2024).

By many measures wealth inequality in the US and globally has increased significantly over the last several decades. The number of billionaires has increased at a staggering rate. Since 1987, Forbes has systematically verified and counted the global number of billionaires. In 1987, Forbes counted 140. Two decades later Forbes tallied a little over 1000. It counted 2000 billionaires in 2017. In 2024 it counted 2,781, and in March this year it counted 3,028 billionaires (a 50% increase in the number of billionaires since 2017 and almost a 9% increase since 2024). Recently I’ve noticed that a new wave of

Recently I’ve noticed that a new wave of

There was a prevailing idea, George Orwell wrote in a 1946 essay

There was a prevailing idea, George Orwell wrote in a 1946 essay

Rania Matar. Samira, Jnah, Beirut, Lebanon, 2021.

Rania Matar. Samira, Jnah, Beirut, Lebanon, 2021.