by Christopher Hall

Sometime towards the end of March in 2016, I exited a movie theater in a white-hot rage. I don’t think my common reactions to bad movies are out of the ordinary – anything bemusement to doubts about the collaborative potential of the human race. (Some movies force you to confront the bald truth that dozens of people were involved in making an abomination, and yet none seemed able to put a stop to it.) But this movie had been a personal insult. Like a child enraged that their parent had “told the story wrong,” I was livid at Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice. Yet I was, at the time, a middle-aged man; now, 9 years later, I’m still middle-aged (more or less), still mad, and I’m still trying to understand why.

It wasn’t that I didn’t understand the movie’s pedigree. The director, Zack Snyder, was clearly a fan of Frank Miller’s 1986 series The Dark Knight Returns, a tale in which an older Batman returns to action in a grim, still crime-ridden Gotham, and which features Superman as a Cold War projection of Reaganite power. I am likewise a fan of that series (although Miller’s Batman: Year One is much better), and of the other series which inaugurated a moment of potential emergence out of the rubric of popular culture for comic books, Alan Moore’s Watchmen – also adapted by Snyder. But it didn’t take long for that emergence to largely trickle out into caricature. The 1990’s were full of supposedly realistic comic books which did little else but glorify cartoonish violence. Sadistic Batmen and evil Supermen proliferated (some, like The Boys’s Homelander, have stuck around). In the 2000’s and 2010’s there were signs of recovery, and thus Snyder’s movie – one in which there is little to differentiate Batman from the thugs he pummels, in which Superman doesn’t smile once and displays an emotional range that rarely deviates from put-upon superiority – was a throwback. After the Bush years and the GWOT, the Great Recession, at the moment in the twilight of the Obama era where we were all justified in asking what exactly his guileless Hope had accomplished, here was a movie that took two icons of justice and transformed them into naked expressions of directionless, pointless power. I realise now, as I did not then (I, along with mostly everybody else, was still at the point where I didn’t take him seriously), that the moment was even more inapt; less than a year earlier, Donald Trump had taken his ride down the escalator.

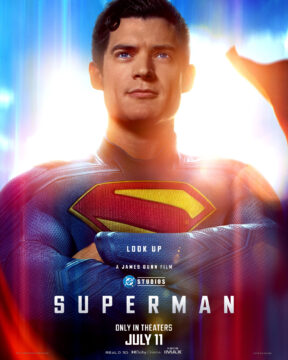

This reflection is occasioned, naturally, by James Gunn’s new movie Superman. I’ve seen it and have to concur with the general consensus: it’s pretty good. It’s goofy without being condescending or idiotic, and there are enough moments of seriousness – should someone with as much power as Superman invade a sovereign country to prevent civilian deaths? – that one’s pleasure in it can be a little less guilty. Gunn’s touchstone extends before the 80’s, to the Silver Age of DC where there was no anxiety about the seriousness of the genre. If elements like Krypto the Superdog were banished in an era where comic books were supposed to display their grit, their return marks an admittance that such exuberance is a strength, not a weakness; a world in which a man can fly might as well have a dog that can fly as well. We haven’t exactly lacked in fresh interpretations of Superman, or other comic books, in the 21st century, but few have reveled in the essential wackiness of the genre as much as Gunn’s.

Even if we must be vigilant in defending a non-transactional version of the Truth, it does not strike me that increased realism – however we want to define this – is necessarily the antidote to the surreality of the moment. If there has been something of an explosion in the quantity and quality of speculative fiction in these past few years, I think it might reasonably coincide with a perceived narrowing of options in the real world. In our political culture, horrible solutions to admittedly intractable problems have overridden the merely bad or ineffective. Actual solutions with potential are whispered about until, on occasion, the whispers become loud enough to be ridiculed (witness the corporate Democratic reaction to Zohran Mamdani). The Trump era in its resistance to the indurated Establishment might have seemed for a moment like an expansion of possibilities, but instead we have their collapse. If we can’t get this essential pliancy from the world, we will create worlds where we can.

So, what does it mean to watch a Superman movie that emphasises the values of hope and kindness in Trump’s second term? Yes, the basic story of Superman has the expected moralistic outlines, but how do we adapt them, or fail to do so, in the present? Leave all this aside; the more important question is whether or not these questions are even worth asking. Martin Scorcese wasn’t exactly wrong when he compared these movies to the mindless entertainment of theme parks, but here we run up against the question of the legitimacy of meaningfulness. Theme parks are mindless entertainment until one evokes, say, memories of a childhood day with a loved one now gone. No one gets to say whether a story is meaningful or not for everybody, but there is a difference between Superman and Citizen Kane – to say nothing of Goodfellas. That the latter are “symbolic” and “meaningful” seems beyond dispute in a way that not everyone will accept as true of the former. Are we stuck at the point where we can say nothing better than “well, it meant something to me?”

So, I’m not trying to claim Superman as high art, but I am wondering how we can articulate the value of a pop culture artifact like it. As famed comic book writer Grant Morrison says in his book Supergods: What Masked Vigilantes, Miraculous Mutants, and a Sun God from Smallville Can Teach Us About Being Human, a will-to-meaning which extends us beyond the point of the incredible story is nearly unavoidable:

We live in the stories we tell ourselves. In a secular, scientific rational culture lacking in and convincing spiritual leadership, superhero stories speak loudly and boldly to out greatest fears, deepest longings, and highest aspirations. They’re not afraid to be hopeful, not embarrassed to be optimistic, and utterly fearless in the dark. They’re about as far from social realism as you can get, but the best superhero stories deal directly with mythic elements of human experience that we can all relate to, in ways that are imaginative, profound, funny, and provocative.

I would disagree with none of this, but there may be a prior step missing here, one that comes before we decide what a story “means.” What I want to unwrap here is the tension between a meaningless bit of entertainment emerging out of the nonsense stories we are most likely to tell children, and a story which reaches the proportions of myth. Superman is mythic in a few senses, the first and most basic of which must be that his story is known to just about everyone. We all know the basics: survivor of a doomed planet comes to earth and uses his great power in the service of humanity. But another crucial aspect to the mythological nature of the story here is the ease with which it can be allegorised. Myths, to my mind, don’t necessarily begin in allegory; they are not necessarily stories where the initial impulse is to render hard-to-understand or abstract phenomena into concrete terms. The “what if” at the beginning of these stories emerges out an uncomplicated desire to stretch the limits of human experience: what if there was a man who was super-strong? What if there was a warrior who was invulnerable, but had a key weakness known only to a few? But it seems to be that simple act of stretching the possibilities that takes us, circuitously, back to human experience: Hercules becomes the symbol of Passion over Reason, Achilles the terrifying disruptive forces of Pride and Anger. Why do we seem to need stories about things that can’t happen to give information about the real world?

Yet complex fantasy literature emerged, and continues to emerge, precisely because it resisted the impulse to allegorisation. Tolkien, in his preface to The Lord of the Rings, insisted that the story not be taken as allegory, and we can understand the impulse to want his story to be read as it was, rather than having his readers checking the events of the narrative against some alternative meaning. Fantasy worlds, or at least well constructed ones, share a quality with what Eric Auerbach identified in Homeric epics; the presence of detail so complete that every shield, sword, hill and tree has some backstory. The world is developed horizontally without some overriding concern for a vertical leap into another realm of signification. Abandoning allegory means that a higher level of energy can be invested in the practice of worldbuilding; it can be an independent act, free from any of the constraints of a bijection with some other set of meanings. It is this worldbuilding – the projection of a reality with new sets of coherent rules different from our own – that contains the richness of speculative fiction.

This is, again, a prior moment; one is eventually going to want to say that this story is significant or symbolic for one reason or another. Perhaps my argument here emerges from my exhaustion with the kinds of allegorisation that are typical at the moment. One suspects that, among the culture warriors of the right, there is a universal crib that dictates their response to anything which doesn’t knuckle under to their demands. (The use of “woke” is creating a kind of infectious semantic satiation where rendering a word meaningless through repetition is slowly making all sorts of discourse inert.) This is not political allegory, but rather allegorical politicisation, the use of a single interpretative key which exposes the “true” meaning of just about anything. (And yes, there is a version of this very common in the academic left). Once allegory becomes the means of rendering every story a roman a clef which conforms exactly to our conceptions, we go beyond the questions of meaninglessness and meaning to mere doublethink. But one can’t help situating these stories in their moment. I know Batman v. Superman wasn’t really “about” Trump or the new era we were all shortly to be corralled into in 2016. I know I ought to resist any similar interpretation about Superman – even though that’s precisely what I’ve engaged in above. The danger felt concerning trivial narratives is that they distract us from the emergencies of the moment; to be entertained is to be blithe. But perhaps the moment of mindlessness is a cleansing, a preparing of ground, ready for investment. It may be true then that non-realist fiction, throwing us into a territory where we are meant merely to luxuriate in the strange detail of it all, succeeds not because it is able to eschew allegory – that’s impossible – but because it is able to delay it.

Or it may all be just nostalgia for the way we heard stories when we children. I don’t remember when I first saw Richard Donner’s 1978 Superman – it came our when I was quite young, so I likely saw it sometime later. But it was a seminal experience for a kid growing up in the 80’s to be sure, and perhaps one’s enthusiasm for just about anything is an echo of that initial limitless joy we once had in the unexpected. Maybe it’s just pure escapism, then, away from a world teetering between the twin abysses of nihilism and lies. But to momentarily escape such a world contains an act of resistance all its own.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.