by David J. Lobina

“To bring attention to this sort of issues is to venture into the psychological factors that underlie nationalist beliefs…and here too the linguistic input is relevant”, I concluded last month, promising to return to this issue in four weeks’ time. And to promise is to send forth, so here we are now.

What else can the linguist say about the nationalist phenomenon, then? As I was at pains to stress last week, the generative approach to the study of language constitutes a cognitive as well as a psychological theory of cognition, and in this sense, its theoretical tools can potentially characterise other mental phenomena, especially those that may be similar to language in one way or another.[i] This seems to be the case for a number of cultural customs, some of which are rather central to the nationalist outlook. Speaking a common language is often the key to developing a national identity within a large population (and thus to properly establish a nation-state), but other factors can be as important.[ii]

The point of contact between language and culture as the linguist views these phenomena is the fact that the linguist’s is a story of how a collection of units and principles combine to yield a rich set of possibilities – mental grammars and the external languages these grammars produce – and something along these lines appears to be true of some forms of culture as well. A number of examples can be found in some of the fields linguistics has influenced over the years, from cognitive psychology and sociology to philosophy. In A Theory of Justice, that well-known classic of political philosophy, John Rawls draws an analogy between the moral judgements people entertain in day-to-day situations and what linguists call grammatical judgements, the also common-enough ability to judge whether a sentence is acceptable or not in one’s own language.[iii] And just as the linguist argues that the capacity to draw grammatical judgements is based on a rich underlying grammar that native speakers are not privy to and whose study require the skills of linguists, Rawls wondered whether this sort of approach was also necessary to account for our capacity to draw moral judgements. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Untitled. April 2021

Sughra Raza. Untitled. April 2021

A rose is a rose is…well, you know. Botanically, a rose is the flower of a plant in the genus Rosa in the family Rosaceae. But roses carry the weight of so much symbolism that a rose is seldom only a rose.

A rose is a rose is…well, you know. Botanically, a rose is the flower of a plant in the genus Rosa in the family Rosaceae. But roses carry the weight of so much symbolism that a rose is seldom only a rose.

By the time I started regular school my father’s home-schooling had prepared me enough to sail through the various half-yearly and annual examinations relatively easily. Indian exams, certainly then and to a large extent even now, do not test your talent or learning ability, they are mainly a test of your memorizing capacity and dexterity in writing coherent answers in a frantic race against time. I found out that I was reasonably proficient in both, and that it is for the lack of proficiency in these two qualities some of my friends, whom I considered highly imaginative and creative, were not doing so well in school.

By the time I started regular school my father’s home-schooling had prepared me enough to sail through the various half-yearly and annual examinations relatively easily. Indian exams, certainly then and to a large extent even now, do not test your talent or learning ability, they are mainly a test of your memorizing capacity and dexterity in writing coherent answers in a frantic race against time. I found out that I was reasonably proficient in both, and that it is for the lack of proficiency in these two qualities some of my friends, whom I considered highly imaginative and creative, were not doing so well in school.

Everyone agrees that early cancer detection saves lives. Yet, practically everyone is busy studying end-stage cancer.

Everyone agrees that early cancer detection saves lives. Yet, practically everyone is busy studying end-stage cancer.

As an aspiring writer of fiction, I like to try and understand the mechanics of what I’m reading. I attempt to ascertain how a writer achieves a certain effect through the manipulation of language. What must happen for us to get “wrapped up” in a story, to lose track of time, to close a book and feel that the world has shifted ever so slightly on its axis? The first step, I think, is for writers to persuade readers to believe in the world of the story. In a first-person narrative, this means that the reader must accept the world of the novel as filtered through the subjective viewpoint of the narrator. But it’s not really the outside world that we are asked to accept, it’s the consciousness of the narrator. To create what I’m calling consciousness—basically, a feeling of being in the world—and to allow the reader to experience it is one of the joys of reading. But how does a writer achieve this mysterious feat?

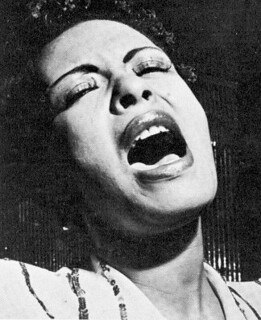

As an aspiring writer of fiction, I like to try and understand the mechanics of what I’m reading. I attempt to ascertain how a writer achieves a certain effect through the manipulation of language. What must happen for us to get “wrapped up” in a story, to lose track of time, to close a book and feel that the world has shifted ever so slightly on its axis? The first step, I think, is for writers to persuade readers to believe in the world of the story. In a first-person narrative, this means that the reader must accept the world of the novel as filtered through the subjective viewpoint of the narrator. But it’s not really the outside world that we are asked to accept, it’s the consciousness of the narrator. To create what I’m calling consciousness—basically, a feeling of being in the world—and to allow the reader to experience it is one of the joys of reading. But how does a writer achieve this mysterious feat? Following Hulu’s release of “The United States vs Billie Holiday”, the singer’s musical career has become a topic of discussion. The docu-drama is based on events in her life after she got out of prison in 1948, having served eight months on a set up drug charge. Now she was again the target of a campaign of harassment by federal agents. Narcotics boss Harry Anslinger was obsessed with stopping her from singing that damn song – Abel Meeropol’s haunting ballad “Strange Fruit”, based on his poem about the lynching of Black Americans in the South. Anslinger feared the song would stir up social unrest, and his agents promised to leave Holiday alone if she would agree to stop performing it in public. And, of course, she refused. In this particular poker game, the top cop had tipped his hand, revealing how much power Holiday must have had to be able to disturb his inner peace.

Following Hulu’s release of “The United States vs Billie Holiday”, the singer’s musical career has become a topic of discussion. The docu-drama is based on events in her life after she got out of prison in 1948, having served eight months on a set up drug charge. Now she was again the target of a campaign of harassment by federal agents. Narcotics boss Harry Anslinger was obsessed with stopping her from singing that damn song – Abel Meeropol’s haunting ballad “Strange Fruit”, based on his poem about the lynching of Black Americans in the South. Anslinger feared the song would stir up social unrest, and his agents promised to leave Holiday alone if she would agree to stop performing it in public. And, of course, she refused. In this particular poker game, the top cop had tipped his hand, revealing how much power Holiday must have had to be able to disturb his inner peace. Wendel White. South Lynn Street School, Seymour, Indiana, 2007.

Wendel White. South Lynn Street School, Seymour, Indiana, 2007.