by Azra Raza

All of the articles in this series can be found here.

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.)

—Walt Whitman

When King Midas asked Silenus what the best thing for man is, Silenus replied, “It is better not to have been born at all. The next best thing for man would be to die quickly.”

When King Midas asked Silenus what the best thing for man is, Silenus replied, “It is better not to have been born at all. The next best thing for man would be to die quickly.”

Herein lies the essential contradiction; we begin to die from the moment of birth. Walt Whitman not only embraces this existential incongruity, he asserts that being contradictory is a positive, desirable virtue: “Do I contradict myself? / Very well then I contradict myself, / (I am large, I contain multitudes).” If you don’t contradict yourself, you are leading a simple, unexamined inner life. His large persona contains opposing, conflicting, paradoxical “multitudes” providing opportunities for self-discovery, and for change. Change is a good thing. Whitman’s friend Emerson summed it up: “A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.”

Enter cancer. The only known lifeform that defies mortality, surpassing the life-death contradiction by achieving man’s ultimate dream of living forever. But at what cost? The immortalized cells burn and blast their way through membranes and organs, scorching tissues, fracturing bones, leaving behind a bloodbath of death and destruction, creeping and crawling into local sanctuaries, swimming in blood vessels, riding in lymphatics, invading new sites, deforming, butchering, exterminating, annihilating, until, in a final act of genocidal-suicidal-homicidal carnage, consuming the mortal host and the immortal unwanted guest alike, a wasted body ends upon a funeral pyre with kilograms of tumor.

Cancer can be perceived as an independent life-form. It is not a parasite because it originates in the host tissue. It is not a “normal” tissue culture cell line that has been induced to grow in vitro, already half-way to transformation. And it is not like jellyfish and other lower order species that can revert to an earlier stage of their lifecycle under stress and restart as newborns. It behaves like a new animal that arises within an animal. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Untitled. April 2021

Sughra Raza. Untitled. April 2021

A rose is a rose is…well, you know. Botanically, a rose is the flower of a plant in the genus Rosa in the family Rosaceae. But roses carry the weight of so much symbolism that a rose is seldom only a rose.

A rose is a rose is…well, you know. Botanically, a rose is the flower of a plant in the genus Rosa in the family Rosaceae. But roses carry the weight of so much symbolism that a rose is seldom only a rose.

By the time I started regular school my father’s home-schooling had prepared me enough to sail through the various half-yearly and annual examinations relatively easily. Indian exams, certainly then and to a large extent even now, do not test your talent or learning ability, they are mainly a test of your memorizing capacity and dexterity in writing coherent answers in a frantic race against time. I found out that I was reasonably proficient in both, and that it is for the lack of proficiency in these two qualities some of my friends, whom I considered highly imaginative and creative, were not doing so well in school.

By the time I started regular school my father’s home-schooling had prepared me enough to sail through the various half-yearly and annual examinations relatively easily. Indian exams, certainly then and to a large extent even now, do not test your talent or learning ability, they are mainly a test of your memorizing capacity and dexterity in writing coherent answers in a frantic race against time. I found out that I was reasonably proficient in both, and that it is for the lack of proficiency in these two qualities some of my friends, whom I considered highly imaginative and creative, were not doing so well in school.

Everyone agrees that early cancer detection saves lives. Yet, practically everyone is busy studying end-stage cancer.

Everyone agrees that early cancer detection saves lives. Yet, practically everyone is busy studying end-stage cancer.

As an aspiring writer of fiction, I like to try and understand the mechanics of what I’m reading. I attempt to ascertain how a writer achieves a certain effect through the manipulation of language. What must happen for us to get “wrapped up” in a story, to lose track of time, to close a book and feel that the world has shifted ever so slightly on its axis? The first step, I think, is for writers to persuade readers to believe in the world of the story. In a first-person narrative, this means that the reader must accept the world of the novel as filtered through the subjective viewpoint of the narrator. But it’s not really the outside world that we are asked to accept, it’s the consciousness of the narrator. To create what I’m calling consciousness—basically, a feeling of being in the world—and to allow the reader to experience it is one of the joys of reading. But how does a writer achieve this mysterious feat?

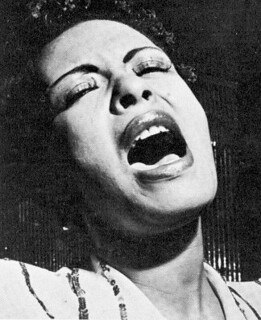

As an aspiring writer of fiction, I like to try and understand the mechanics of what I’m reading. I attempt to ascertain how a writer achieves a certain effect through the manipulation of language. What must happen for us to get “wrapped up” in a story, to lose track of time, to close a book and feel that the world has shifted ever so slightly on its axis? The first step, I think, is for writers to persuade readers to believe in the world of the story. In a first-person narrative, this means that the reader must accept the world of the novel as filtered through the subjective viewpoint of the narrator. But it’s not really the outside world that we are asked to accept, it’s the consciousness of the narrator. To create what I’m calling consciousness—basically, a feeling of being in the world—and to allow the reader to experience it is one of the joys of reading. But how does a writer achieve this mysterious feat? Following Hulu’s release of “The United States vs Billie Holiday”, the singer’s musical career has become a topic of discussion. The docu-drama is based on events in her life after she got out of prison in 1948, having served eight months on a set up drug charge. Now she was again the target of a campaign of harassment by federal agents. Narcotics boss Harry Anslinger was obsessed with stopping her from singing that damn song – Abel Meeropol’s haunting ballad “Strange Fruit”, based on his poem about the lynching of Black Americans in the South. Anslinger feared the song would stir up social unrest, and his agents promised to leave Holiday alone if she would agree to stop performing it in public. And, of course, she refused. In this particular poker game, the top cop had tipped his hand, revealing how much power Holiday must have had to be able to disturb his inner peace.

Following Hulu’s release of “The United States vs Billie Holiday”, the singer’s musical career has become a topic of discussion. The docu-drama is based on events in her life after she got out of prison in 1948, having served eight months on a set up drug charge. Now she was again the target of a campaign of harassment by federal agents. Narcotics boss Harry Anslinger was obsessed with stopping her from singing that damn song – Abel Meeropol’s haunting ballad “Strange Fruit”, based on his poem about the lynching of Black Americans in the South. Anslinger feared the song would stir up social unrest, and his agents promised to leave Holiday alone if she would agree to stop performing it in public. And, of course, she refused. In this particular poker game, the top cop had tipped his hand, revealing how much power Holiday must have had to be able to disturb his inner peace. Wendel White. South Lynn Street School, Seymour, Indiana, 2007.

Wendel White. South Lynn Street School, Seymour, Indiana, 2007.