by Joseph Shieber

I first became aware of the historian Allen Guelzo’s work due to a mention in a recent newspaper column — just not the mention that, if you’re active on Twitter (and particularly philosophy Twitter), you might be expecting.

In a glowing review in the Washington Post, George Will praised Guelzo’s new biography of Robert E. Lee for Guelzo’s unwillingness to buy in to the hagiography associated with the reverence for Lee that characterized so many 20th century assessments.

Here’s a sample:

Lee, Guelzo writes, “raised his hand” against the nation that, as an Army officer, he had sworn to defend. He did so for an agenda that a much greater man, Ulysses S. Grant, called one of “the worst for which a people ever fought.” Lee thought slavery was a “greater evil” to White people than to Black people. He enveloped himself in what Guelzo calls a “cloud of pious wishes” and decided, as Guelzo tartly says, “it was up to the whites to decide when enough was enough.” Guelzo writes that to Lee, slavery’s victims were “invisible, despite their presence all around.” His indifference was “cruelty in self-disguised velvet.” Not well disguised, when he presided at the whipping of three recaptured runaways, ordering a constable to “lay it on well.”

Given the care that Guelzo obviously devotes to getting the details right in his widely praised historical works, it was surprising for me to see that he was being roasted on Twitter for some glaringly inaccurate pronouncements on Kant.

The impetus for the derision being heaped on Guelzo was a column — again in the Washington Post — in which Marc Thiessen attempted “to explain CRT [Critical Race Theory] and why it is so dangerous”. Read more »

Tick, Tick . . . Boom!

Tick, Tick . . . Boom! Of the senior professors at MIT other than Samuelson and Solow, I had a somewhat close relationship with Paul Rosenstein-Rodan, a pioneer in development economics. He had grown up in Vienna and taught in England before reaching MIT. He had advised governments in many countries, and was full of stories. In India he knew Nehru and Sachin Chaudhuri well. He had an excited, omniscient way of talking about various things. At the beginning of our many long conversations he asked me what my politics was like. I said “Left of center, though many Americans may consider it too far left while several of my Marxist friends in India do not consider it left enough”. As someone from ‘old Europe’ he understood, and immediately put his hand on his heart and said “My heart too is located slightly left of center”.

Of the senior professors at MIT other than Samuelson and Solow, I had a somewhat close relationship with Paul Rosenstein-Rodan, a pioneer in development economics. He had grown up in Vienna and taught in England before reaching MIT. He had advised governments in many countries, and was full of stories. In India he knew Nehru and Sachin Chaudhuri well. He had an excited, omniscient way of talking about various things. At the beginning of our many long conversations he asked me what my politics was like. I said “Left of center, though many Americans may consider it too far left while several of my Marxist friends in India do not consider it left enough”. As someone from ‘old Europe’ he understood, and immediately put his hand on his heart and said “My heart too is located slightly left of center”.

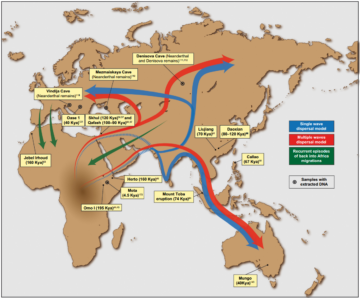

Our human story has never been simple or monotonous. In fact, it has been nothing less than epic. Beginning from relatively small populations in Africa, our ancestors

Our human story has never been simple or monotonous. In fact, it has been nothing less than epic. Beginning from relatively small populations in Africa, our ancestors  hookers rested after walking Hollywood Boulevard, or at least that’s what my mother once said of her counterparts who lived in rooms above the garages of a small apartment building on a busy street. While waiting for my father to return from prison, we lived in one of the garages, converted into a shelter.

hookers rested after walking Hollywood Boulevard, or at least that’s what my mother once said of her counterparts who lived in rooms above the garages of a small apartment building on a busy street. While waiting for my father to return from prison, we lived in one of the garages, converted into a shelter. Catharine Ahearn. Incredible Hulk, 2014. In the exhibition “Everything Falls Faster Than An Anvil”.

Catharine Ahearn. Incredible Hulk, 2014. In the exhibition “Everything Falls Faster Than An Anvil”.

Do we Americans really have a shared, founding mythology that unites us in a desire to work together for the common good?

Do we Americans really have a shared, founding mythology that unites us in a desire to work together for the common good?  It’s still a year away, maybe three, but you can see it coming.

It’s still a year away, maybe three, but you can see it coming.