by David J. Lobina

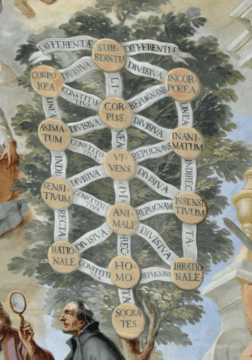

In my series on Language and Thought, I defended a number of ideas; to wit, that there is such a thing as a language of thought, a conceptual representational system in which most of human cognition is carried out (or more centrally, the process of belief-fixation, or thinking tout court, where different kinds of information – visual, aural, information from memory or other held beliefs – are gathered and combined into new beliefs and thoughts); that the language of thought (LoT) is not a natural language (that is, it is not, for instance, English); that cross-linguistic differences do not result in different thinking schemes (that is, different LoTs); that inner speech (the writers’ interior monologue) is not a case of thinking per se; and that the best way to study the LoT is through the study of natural language, though from different viewpoints.

In the following two posts, I shall change tack a little bit and consider an alternative approach (as well as some alternative conclusions), at least on some rather specific cases (see endnote 1). As pointed out in the already mentioned series on the LoT, the study of human thought can be approached from many different perspectives; central among these is to study the “form” or “shape” thought has through an appropriately-focused analysis of language and linguistic structure – my take – a position that raises the big issue of how language and thought at all relate.

And in considering the relationship between language and thought, it is often supposed that the rather sophisticated cognitive abilities of preverbal infants and infraverbal animal species demonstrate that some form of thought is possible without language. That is, that thought does not depend upon having a natural language, given that many non-linguistic abilities are presumably underlain by a medium other than a natural language. Read more »

This past spring, I found myself sitting, masked, at a wooden desk among a scattering of scientific researchers at the Museo Galileo in Florence. Next to me was a thick reference book on the history of astronomical instruments and a smaller work on the sundials and other measuring devices built into the churches of Florence to mark the cyclical turning points of cosmic time. The gnomon of Santa Maria del Fiore, for instance, consisted of a bronzina, a small hole set into the lantern ninety meters above that acted as a camera oscura and projected an image of the sun onto the cathedral floor far below. At noon on the day of the solstice, the solar disc superimposed itself perfectly onto a round marble slab, not quite a yard in diameter, situated along the inlaid meridian. I studied the explanations of astronomical quadrants and astrolabes and the armilla equinoziale, the armillary sphere of Santa Maria Novella, made up of two conjoined iron rings mounted on the façade that told the time of day and year based on the position of their elliptical shadow, when all at once it occurred to me that I’d wanted to write about something else altogether, about a person I occasionally encountered, a phantom living somewhere inside me: the young woman who’d decided not to leave, not to move to Berlin after all, to rip up the letter of acceptance to the art academy she received all those years ago and to stay put, in New York. Alive somewhere, in some other iteration of being, was a parallel existence in an alternative universe, one of the infinite spheres of possibility in which I’d decided differently and become a different woman.

This past spring, I found myself sitting, masked, at a wooden desk among a scattering of scientific researchers at the Museo Galileo in Florence. Next to me was a thick reference book on the history of astronomical instruments and a smaller work on the sundials and other measuring devices built into the churches of Florence to mark the cyclical turning points of cosmic time. The gnomon of Santa Maria del Fiore, for instance, consisted of a bronzina, a small hole set into the lantern ninety meters above that acted as a camera oscura and projected an image of the sun onto the cathedral floor far below. At noon on the day of the solstice, the solar disc superimposed itself perfectly onto a round marble slab, not quite a yard in diameter, situated along the inlaid meridian. I studied the explanations of astronomical quadrants and astrolabes and the armilla equinoziale, the armillary sphere of Santa Maria Novella, made up of two conjoined iron rings mounted on the façade that told the time of day and year based on the position of their elliptical shadow, when all at once it occurred to me that I’d wanted to write about something else altogether, about a person I occasionally encountered, a phantom living somewhere inside me: the young woman who’d decided not to leave, not to move to Berlin after all, to rip up the letter of acceptance to the art academy she received all those years ago and to stay put, in New York. Alive somewhere, in some other iteration of being, was a parallel existence in an alternative universe, one of the infinite spheres of possibility in which I’d decided differently and become a different woman. Among other things London School of Economics is associated in my mind with bringing me in touch with one of the most remarkable persons I have ever met in my life, and someone who has been a dear friend over nearly four decades since then. This is Jean Drèze.

Among other things London School of Economics is associated in my mind with bringing me in touch with one of the most remarkable persons I have ever met in my life, and someone who has been a dear friend over nearly four decades since then. This is Jean Drèze. Although by no means the only ones, two models of human beings and their relation to society are prominent in modern social and political thought. At first glance they seem incompatible, but I want to sketch them out and start to establish how they might plausibly be made to fit together.

Although by no means the only ones, two models of human beings and their relation to society are prominent in modern social and political thought. At first glance they seem incompatible, but I want to sketch them out and start to establish how they might plausibly be made to fit together.

Anneliese Hager. Untitled. ca. 1940-1950

Anneliese Hager. Untitled. ca. 1940-1950

“

“ Francis Fukuyama does not mind having to play defense. Recognizing that the problems plaguing liberal societies result in no small part from the flaws and weaknesses of liberalism itself, he argues in Liberalism and its Discontents (Profile Books: 2022) that the response to these problems, all said and done, is liberalism. This requires some courage: three decades ago, Fukuyama may have captured the spirit of the age, but the spirit has grown impatient with liberalism as of late. Fukuyama, however, does not think of it as a worn-out ideal. He has taken note of right-wing assaults, as well as progressive criticisms that suggest a need to go beyond it; and his verdict is that any attempt at improvement will either stay in a liberal orbit or lead to political decay. Liberalism is still the best we have got.

Francis Fukuyama does not mind having to play defense. Recognizing that the problems plaguing liberal societies result in no small part from the flaws and weaknesses of liberalism itself, he argues in Liberalism and its Discontents (Profile Books: 2022) that the response to these problems, all said and done, is liberalism. This requires some courage: three decades ago, Fukuyama may have captured the spirit of the age, but the spirit has grown impatient with liberalism as of late. Fukuyama, however, does not think of it as a worn-out ideal. He has taken note of right-wing assaults, as well as progressive criticisms that suggest a need to go beyond it; and his verdict is that any attempt at improvement will either stay in a liberal orbit or lead to political decay. Liberalism is still the best we have got. Every now and then, a nation becomes modern. Greeks and Poles and Russians were modern, for a time. Now it’s the Ukrainians’ turn.

Every now and then, a nation becomes modern. Greeks and Poles and Russians were modern, for a time. Now it’s the Ukrainians’ turn. As the January 6th hearings continue and Americans watch

As the January 6th hearings continue and Americans watch