by Andrea Scrima

This past spring, I found myself sitting, masked, at a wooden desk among a scattering of scientific researchers at the Museo Galileo in Florence. Next to me was a thick reference book on the history of astronomical instruments and a smaller work on the sundials and other measuring devices built into the churches of Florence to mark the cyclical turning points of cosmic time. The gnomon of Santa Maria del Fiore, for instance, consisted of a bronzina, a small hole set into the lantern ninety meters above that acted as a camera oscura and projected an image of the sun onto the cathedral floor far below. At noon on the day of the solstice, the solar disc superimposed itself perfectly onto a round marble slab, not quite a yard in diameter, situated along the inlaid meridian. I studied the explanations of astronomical quadrants and astrolabes and the armilla equinoziale, the armillary sphere of Santa Maria Novella, made up of two conjoined iron rings mounted on the façade that told the time of day and year based on the position of their elliptical shadow, when all at once it occurred to me that I’d wanted to write about something else altogether, about a person I occasionally encountered, a phantom living somewhere inside me: the young woman who’d decided not to leave, not to move to Berlin after all, to rip up the letter of acceptance to the art academy she received all those years ago and to stay put, in New York. Alive somewhere, in some other iteration of being, was a parallel existence in an alternative universe, one of the infinite spheres of possibility in which I’d decided differently and become a different woman.

This past spring, I found myself sitting, masked, at a wooden desk among a scattering of scientific researchers at the Museo Galileo in Florence. Next to me was a thick reference book on the history of astronomical instruments and a smaller work on the sundials and other measuring devices built into the churches of Florence to mark the cyclical turning points of cosmic time. The gnomon of Santa Maria del Fiore, for instance, consisted of a bronzina, a small hole set into the lantern ninety meters above that acted as a camera oscura and projected an image of the sun onto the cathedral floor far below. At noon on the day of the solstice, the solar disc superimposed itself perfectly onto a round marble slab, not quite a yard in diameter, situated along the inlaid meridian. I studied the explanations of astronomical quadrants and astrolabes and the armilla equinoziale, the armillary sphere of Santa Maria Novella, made up of two conjoined iron rings mounted on the façade that told the time of day and year based on the position of their elliptical shadow, when all at once it occurred to me that I’d wanted to write about something else altogether, about a person I occasionally encountered, a phantom living somewhere inside me: the young woman who’d decided not to leave, not to move to Berlin after all, to rip up the letter of acceptance to the art academy she received all those years ago and to stay put, in New York. Alive somewhere, in some other iteration of being, was a parallel existence in an alternative universe, one of the infinite spheres of possibility in which I’d decided differently and become a different woman.

Not long before this, a friend in Graz had told me that she’d been born on American soil and so, theoretically at least, was an American citizen. She’d never lived there, however, and this was her ghost, her own parallel existence. In July of 1950, her parents had sailed from Bremerhaven to New York on the United States Army Transport W.G. Haan, a ship of displaced persons that had been reacquired by the Navy and enlisted in the Military Sea Transportation Service. Their intention was to emigrate; they’d applied for their visas, all their papers were in order, and yet they were refused entry and caught in limbo for more than a year before being sent back to Europe. My friend was born in this limbo, on Ellis Island.

The first time she’d decided to research the ship manifests and to see what information she could find about her parents’ voyage and subsequent internment, she stumbled, one might say improbably, on a photograph of her mother, taken aboard the ship, posted online by the Immigration History Research Center Archives of the University of Minnesota Libraries. It was part of a series a Latvian passenger named Uģis Skrastiņš had taken to document his trip after leaving a displaced persons camp in Meersbeck, Germany, before eventually resettling in Minneapolis. The collection held a total of 87 photographs recording trains arriving, passengers disembarking, and people standing in line on a dock, waiting to board with manila tags attached to the buttons of their coats, blankets strapped to the suitcases resting on the pavement next to them. People crowded the ship’s deck, near-silhouettes against the churning, metallic-looking water below; crew members handled ropes as thick as their arms, with heavy black smoke curling upwards from another ship’s funnel behind them, and everywhere the latticework of huge metal cranes ready to haul up cargo. Again and again, I came back to the photograph of my friend’s mother. She was smiling, her eyes were downcast, and she seemed to be unaware that she was being photographed; her smile was private, reserved for my friend’s father, the man in the foreground with his back turned to us and his head slightly tilted, also smiling. It was July, and while the ocean air must have had a nip to it, as the people in the photograph were wearing coats, my friend’s mother was wearing hers open. She was two weeks pregnant with my friend; presumably, she didn’t yet know this. Her hair was in place, as was her husband’s: the day was not particularly windy, and two women seated in the background, one of them with a kerchief tied under her chin, seemed to be enjoying the sea air.

The first time she’d decided to research the ship manifests and to see what information she could find about her parents’ voyage and subsequent internment, she stumbled, one might say improbably, on a photograph of her mother, taken aboard the ship, posted online by the Immigration History Research Center Archives of the University of Minnesota Libraries. It was part of a series a Latvian passenger named Uģis Skrastiņš had taken to document his trip after leaving a displaced persons camp in Meersbeck, Germany, before eventually resettling in Minneapolis. The collection held a total of 87 photographs recording trains arriving, passengers disembarking, and people standing in line on a dock, waiting to board with manila tags attached to the buttons of their coats, blankets strapped to the suitcases resting on the pavement next to them. People crowded the ship’s deck, near-silhouettes against the churning, metallic-looking water below; crew members handled ropes as thick as their arms, with heavy black smoke curling upwards from another ship’s funnel behind them, and everywhere the latticework of huge metal cranes ready to haul up cargo. Again and again, I came back to the photograph of my friend’s mother. She was smiling, her eyes were downcast, and she seemed to be unaware that she was being photographed; her smile was private, reserved for my friend’s father, the man in the foreground with his back turned to us and his head slightly tilted, also smiling. It was July, and while the ocean air must have had a nip to it, as the people in the photograph were wearing coats, my friend’s mother was wearing hers open. She was two weeks pregnant with my friend; presumably, she didn’t yet know this. Her hair was in place, as was her husband’s: the day was not particularly windy, and two women seated in the background, one of them with a kerchief tied under her chin, seemed to be enjoying the sea air.

Upon their arrival in New York, my friend’s parents were interned on Ellis Island, where they lived for fifteen months and waited for their papers to be processed. Several native Slovenes who were now naturalized American citizens, including a lawyer and a representative of the Catholic Church, had vouched for my friend’s father; his application for an immigration visa, which he’d submitted back in Graz, had already been approved. My friend’s father spoke Slovenian, German, French, Latin and Greek from school, as well as the Italian he’d learned during the few months he’d spent in an internment camp; on Ellis Island, he’d been initially assigned to kitchen work and had learned English quickly, and was soon helping with the center’s logistics. At war’s end, my friend’s mother had fled to a refugee camp the British ran in Judenburg, situated 50 miles northeast of Graz, and because she could type, she was entrusted with administrative work and also absorbed English quickly.

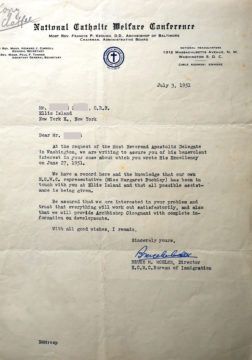

Two months after their arrival, the Internal Security Act of 1950 was signed into law to counteract domestic subversion and threats to internal security; it stipulated the mandatory registration of all communist organizations and allowed for the “emergency detention” of anyone deemed suspicious. During the months my friend’s father had spent in a displaced persons camp in East Tyrol, he’d bunked with another Slovene who’d been charged with theft, thrown out of the camp, and deported to Yugoslavia. Sometime later, for unknown reasons, this man denounced my friend’s father, claiming that he’d witnessed him passing information along to Tito’s partisans; he made his allegation directly to the British occupying authorities. Although the immigration officials might have exhibited caution in taking the word of a criminal, or asked themselves what benefits or mitigating circumstances the latter might have counted on in return—or guessed how unlikely it was for a devout Catholic to want to help the very Communists who had robbed him of his homeland—my friend’s father eventually received a notification barring entry into the United States. There was no explanation given. Citing national security and stating that to disclose the evidence leading to his permanent exclusion without hearing would be “prejudicial to the public interest,” as pursuant to Title 8, Code of Federal Regulations 175.57, the United States Department of Justice—pressed by a lawyer interested in my friend’s father’s case and writing to them six years later from the Graybar Building in New York—declined to provide specifics.

I wondered if the fifteen months the young couple had spent in New York felt as though they’d taken place on a different temporal plane, remembered afterwards as a kind of interstice situated somewhere outside the disruptions and continuities of their lives. In any case, my friend was born and baptized in this interstice, where, following the family’s return to Europe, the seed of her own phantom self was planted and grew in her absence. In another universe, unbeknownst to her as she was running around playing in the streets of Graz, one of my friend’s alternative selves was busy toppling a tower of building blocks somewhere on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, in the Germantown part of Yorkville; or in Bridgeport, Connecticut, home to a large Slovene community that spoke her father’s native tongue. Perhaps she called herself Gloria, the name a friend of her mother’s suggested at her christening. But my friend’s name wasn’t Gloria, and she didn’t wish she’d grown up in America, because in another universe, she did, in fact, grow up in America—and she was presently living her life there, one of the infinite possible outcomes of an infinitely layered reality, had certain parameters of possibility lurking in every decision and chance occurrence turned out differently.

Parallel time; lost time. The sundials in Santa Maria Novella, designed by the Dominican priest Egnazio Danti, mathematician and cosmographer of the Grand Duke Cosimo I dei Medici, supported the theory that the ancient Julian calendar had led to an accumulated discrepancy of ten days, thereby bringing the liturgical dates of the Church out of synch with celestial time. Several years later, Pope Gregory XIII finally issued a papal bull that approved a correction of the Julian year, turning October 5, 1582 into October 15 and eradicating ten entire days. As I wondered about these phantom days and the potential effects of their deletion, I heard the bells of the Basilica Santa Croce ring seventeen times for the seventeen days that had passed since Russia had invaded Ukraine. Returning to my room later in the day, I learned that this act of solidarity was based on a long-standing alliance: in 1966, when the River Arno flooded its banks and destroyed many of the works in nearby churches and libraries, including the underground storage chambers of the Uffizi Galleries, the fragile layers of paint that had managed to cling to the wood of the gigantic Cimabue crucifix for seven hundred years peeled off, causing irreparable damage. Kiev immediately offered Florence financial assistance to tackle the tons of mud that had clogged its streets and buildings; the two became sister cities three years later. And so when the mayor of Florence called for a large demonstration in support of Ukraine, at which Zelenskyy spoke live from a large video screen in the Piazza Santa Croce, where the Cimabue cross hangs in the church’s sacristy, it was not the first public act of friendship between the cities: in 2015, a year after Russia annexed the Crimean Peninsula, a monument to Dante Alighieri was erected in Volodymyrska Hill Park, inspiring the people of Kiev to envisage the divine comedy currently unfolding in their lives and consider each crime’s fitting retribution, while four days previously, Vitali Klitschko, mayor of Kiev, had arrived in Florence to unveil a statue of Ukrainian artist and poet Taras Shevchenko in the square in front of the Biblioteca delle Oblate. Speaking across the centuries to Shevchenko, who asked to be remembered “with gentle whispers and kind words [. . .] when the blood of Ukraine’s foes flows into the blue waters of the sea,” Dante’s Canto XII describes the punishment he reserved for warmongers, whom he relegated to the first ring of the seventh circle of Hell along with murderers, tyrants, and plunderers, where they were damned to writhe in the flames and the boiling blood of the River Phlegethon—guarded by the raging Minotaur and an army of Centaurs shooting arrows at anyone trying to rise above the seething stench—to torment them for all the horrors they inflicted and the lives they destroyed and the blood they caused to be spilled, for all eternity.

In the meantime, my Ellis Island-born friend had scanned a few new documents and mailed them to me; I saw that she had been delivered in the U.S. Marine Hospital in Stapleton, which was later privatized and renamed Bayley Seton, and I wondered at the odds that this child of would-be immigrants from Vojvodina and Slovenia should turn out to be, like me, a native Staten Islander. The U.S. Marine was built on the site of the original Seaman’s Retreat, Staten Island’s first hospital, a section of which was used for quarantine facilities after another hospital around a mile to the north was burned down in the riots that sparked the so-called Staten Island Quarantine War of 1858. At the time, standard practice had been to redirect immigrant ships found, upon inspection, to carry infected passengers from the Brooklyn and Manhattan docks to the waterfront hospital; common diseases were smallpox, yellow fever, cholera, and typhus. During the decade of the 1850s, more than two million immigrants had arrived in New York City, half the population of which was already foreign-born; by contrast, Staten Island was still largely rural, with a few small towns scattered on the North Shore and a population numbering barely over 20,000. Medical theory at the time held that infectious disease was caused by an unidentified noxious airborne substance that thrived in the dark, damp holds of the ships’ steerage, fermenting throughout the weeks of the overseas passage into a miasma of pestilent vapors that could cling to bodies and clothing or be blown ashore with the wind. Xenophobia blended with a fear of contagion, and local residents had long blamed the hospital for various outbreaks; after decades of unsuccessful political protest, and following a renewed emergence of the dreaded yellow fever, they finally took matters into their own hands and defied the city authorities. At a time when the microbial origin of infectious disease was still unknown—it was believed that even very ill patients, once they were thoroughly scrubbed and given clean clothing, did not themselves spread the contagion—the rioters carried the sick, still lying on their mattresses, out of the wards and deposited them on the lawn outside before setting fire to the buildings and razing everything to the ground. The dramatic events brought locals into close physical contact with the hospital’s entire population of infected patients, and, as to be expected, precipitated further outbreaks of disease in the neighboring towns—the precise origin of which remained, of course, unknown and the subject of further alarm and speculation.

In the meantime, my Ellis Island-born friend had scanned a few new documents and mailed them to me; I saw that she had been delivered in the U.S. Marine Hospital in Stapleton, which was later privatized and renamed Bayley Seton, and I wondered at the odds that this child of would-be immigrants from Vojvodina and Slovenia should turn out to be, like me, a native Staten Islander. The U.S. Marine was built on the site of the original Seaman’s Retreat, Staten Island’s first hospital, a section of which was used for quarantine facilities after another hospital around a mile to the north was burned down in the riots that sparked the so-called Staten Island Quarantine War of 1858. At the time, standard practice had been to redirect immigrant ships found, upon inspection, to carry infected passengers from the Brooklyn and Manhattan docks to the waterfront hospital; common diseases were smallpox, yellow fever, cholera, and typhus. During the decade of the 1850s, more than two million immigrants had arrived in New York City, half the population of which was already foreign-born; by contrast, Staten Island was still largely rural, with a few small towns scattered on the North Shore and a population numbering barely over 20,000. Medical theory at the time held that infectious disease was caused by an unidentified noxious airborne substance that thrived in the dark, damp holds of the ships’ steerage, fermenting throughout the weeks of the overseas passage into a miasma of pestilent vapors that could cling to bodies and clothing or be blown ashore with the wind. Xenophobia blended with a fear of contagion, and local residents had long blamed the hospital for various outbreaks; after decades of unsuccessful political protest, and following a renewed emergence of the dreaded yellow fever, they finally took matters into their own hands and defied the city authorities. At a time when the microbial origin of infectious disease was still unknown—it was believed that even very ill patients, once they were thoroughly scrubbed and given clean clothing, did not themselves spread the contagion—the rioters carried the sick, still lying on their mattresses, out of the wards and deposited them on the lawn outside before setting fire to the buildings and razing everything to the ground. The dramatic events brought locals into close physical contact with the hospital’s entire population of infected patients, and, as to be expected, precipitated further outbreaks of disease in the neighboring towns—the precise origin of which remained, of course, unknown and the subject of further alarm and speculation.

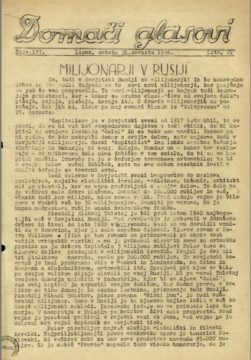

My friend’s father was interned in the Lienz-Peggetz camp in East Tyrol, Austria, from November 1, 1945 to July 1, 1946. During this time, he worked for the Slovene refugee newspaper Domači glasovi (Voices from Home), which was written, edited, and printed on camp premises. Because the British occupying authorities prohibited the publication of periodicals, the editor-in-chief, Father France Blatnik, claimed that the copies he distributed at the camp had been printed in Klagenfurt and pretended to pick them up each day from the train station. The British knew, of course, turned a blind eye, and in any case, as the Slovenes proved to be model internees who kept the camp running smoothly, later lifted the restriction.

Information was gleaned from British and American newspapers, British and Slovene radio broadcasts, eye-witness accounts, and from Slovene and other Yugoslav, i.e., Tito’s, press. The objective was to keep the Slovene refugees informed about what was happening in the homeland and in Lienz-Peggetz and other camps in Austria and Italy and to report on trials and convictions as well as agreements between the Allied powers that were certain to impact events unfolding in the country. The camp’s inhabitants had already learned the grim fate of the anti-partisan Domobranci, the Slovene Home Guard, over ten thousand of whom were executed without trial after the British authorities forcibly repatriated them under the pretext of sending them to Italy and to safety. Increasingly, hopes of returning home were replaced with the uncertain prospect of emigration. As Catholics and staunch anti-communists, the paper’s editors must have feared that the British might send the civilians back to Yugoslavia as well, where they would be detained and, because of their allegiance to the Church, parts of which had aligned itself with the fascists, deemed collaborators and thrown into prison, or worse. But because Domači glasovi was subject to British censorship, they had no choice but to keep this fear to themselves and their readers from falling into despair.

The editors of Domači glasovi and other Slovene camp newspapers encouraged internees to write to compatriots who had already succeeded in emigrating to Canada, the U.S., and South America and urge them not to believe the propaganda the Yugoslav state was spreading about the Catholic-led resistance. In January of 1946, overseas postal service was reinstated in Austria to all countries except Germany and Japan, and Domači glasovi listed the fees for postcards and letters and detailed what the camp authorities did and didn’t allow. The sender’s name had to be printed clearly on the back of each letter in the upper left-hand corner. Photographs were not allowed; shorthand and pre-stamped envelopes were not allowed. The use of code to convey messages other than the letter’s ostensible content was prohibited, as was invisible ink or anything else that could transmit content in a way that kept it secret from the camp authorities. Also strictly prohibited: any action against or objection to the interests of order and security on the part of the occupying troops and authorities. The editors asked the internees to write on the “thinnest possible paper” and use the “thinnest possible envelopes” so that the letters could be sent by air mail.

As I tried to piece together daily life at the camp, making my way through issue after issue of Domači glasovi, the complete set of which had been digitized and published online, I copied out random paragraphs and fed them into Google Translate. Sometimes the scan was too faint for the optical character recognition software to register the letters properly, and the result was a peculiar fingerprint of archival deterioration pierced by words and phrases that rang out from the nonsense and brought the harsh reality of the time momentarily back into focus: “noizmomc cen, achieved vej žku zmrg ‘Tfir was the one ide 1 that. all the wars n vdrhnil and provovrl ju ške defenders of freedom – mili new people z-dried diesel., sc were forced to live in hiding® Zg-dlla.” I searched the issues from the summer of 1945 for any mention of the thousands of Russian and Ukrainian Cossacks who had been camping out in the immediate vicinity until June 1, 1945, when the occupying forces handed them over to the Soviet army, but found nothing; it finally occured to me that the editors would have been unwise, even if it were to pass the censors, to mention that the British had betrayed them, as well. 2,479 of these Cossacks, most of them officers and their families, had been living in the very same camp until four days previously, when the British authorities, giving them their word of honor that they were merely bringing them to a conference and that they would be returned by 6 p.m. the same day, led them out of Lienz-Peggetz with the intention of transporting them to the USSR. When the Cossacks realized what was happening, they refused to board the trucks and British soldiers began beating them. Many of them committed suicide on the spot; thousands more would follow suit in the days and weeks to come. It’s difficult to imagine that internees with any clear knowledge of the circumstances leading to these events, among them, presumably, my friend’s father, would have felt safe, regardless of how impeccably they ran the camp—which included a comprehensive registration system of all the camp’s residents; sub-committees that organized everything to do with work, housing, food, health, welfare, and education; professionally staffed elementary schools, secondary schools, and adult education; a medical and dental clinic; and various workshops—or how warm and seemingly sincere the British praise of their remarkable discipline might have been.

As I tried to piece together daily life at the camp, making my way through issue after issue of Domači glasovi, the complete set of which had been digitized and published online, I copied out random paragraphs and fed them into Google Translate. Sometimes the scan was too faint for the optical character recognition software to register the letters properly, and the result was a peculiar fingerprint of archival deterioration pierced by words and phrases that rang out from the nonsense and brought the harsh reality of the time momentarily back into focus: “noizmomc cen, achieved vej žku zmrg ‘Tfir was the one ide 1 that. all the wars n vdrhnil and provovrl ju ške defenders of freedom – mili new people z-dried diesel., sc were forced to live in hiding® Zg-dlla.” I searched the issues from the summer of 1945 for any mention of the thousands of Russian and Ukrainian Cossacks who had been camping out in the immediate vicinity until June 1, 1945, when the occupying forces handed them over to the Soviet army, but found nothing; it finally occured to me that the editors would have been unwise, even if it were to pass the censors, to mention that the British had betrayed them, as well. 2,479 of these Cossacks, most of them officers and their families, had been living in the very same camp until four days previously, when the British authorities, giving them their word of honor that they were merely bringing them to a conference and that they would be returned by 6 p.m. the same day, led them out of Lienz-Peggetz with the intention of transporting them to the USSR. When the Cossacks realized what was happening, they refused to board the trucks and British soldiers began beating them. Many of them committed suicide on the spot; thousands more would follow suit in the days and weeks to come. It’s difficult to imagine that internees with any clear knowledge of the circumstances leading to these events, among them, presumably, my friend’s father, would have felt safe, regardless of how impeccably they ran the camp—which included a comprehensive registration system of all the camp’s residents; sub-committees that organized everything to do with work, housing, food, health, welfare, and education; professionally staffed elementary schools, secondary schools, and adult education; a medical and dental clinic; and various workshops—or how warm and seemingly sincere the British praise of their remarkable discipline might have been.

In the report “Psychological Problems of Displaced Persons,” written for the UNRRA (United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration), the British, American, and Dutch authors described various recurrent characteristics, including the “high importance of the need to be loved and valued” and what happened to people when this need was deprived; “the meaning of comfort and security”; “psychological hindrances to reassimilation”; “the way in which refugees banish painful memories”; “bitterness and touchiness”; “undercurrents of hostility”; as well as feelings of guilt, depression, and tendencies toward self-destructiveness. In the children, they observed how a return home can become a new ‘displacement’ if all they’ve known is the land they’ve been exiled to, as well as how the general trauma of displacement can lead to mistrust, violence, greediness, sexual precociousness, a feeling of being dirty, and a deep sense of guilt. Indeed, guilt seems to be the most persistent, and most frequently repressed, emotion, and the individual often feels like an outcast if he or she made political decisions that later precluded repatriation, regardless of whether these decisions sprang from moral conscience or a sense of duty: a feeling of shame lingered on a level so subliminal that it was hard to identify, let alone repudiate. At the same time, the detainees’ surviving journals offered psychological insight into the mental state of the military officers, UNRRA, and Red Cross employees they were forced to deal with on a daily basis, interpreting their character weaknesses and hypocrisies, observing that some of them were just as afraid of getting fired as they themselves were of being sent back to Tito’s Yugoslavia, and likening their dread to the dilemma faced by a convict who, after having finished his prison sentence, is suddenly faced with the terrifying prospect of freedom and having to learn to navigate again in civil society.

Yet all this time, as I was researching the fate of the Slovenian refugees, most of whom had long since passed away, hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians who were still alive, but some of whom would no longer be alive a day or an hour later, continued to flee advancing troops. Our minds are trained on news cycles calibrated, in a never-ending feedback loop, to attention spans that have shortened considerably since the advent of the internet; it is difficult to sustain a position in the long term when an overwhelming sense of powerlessness and the apathy it gives rise to gradually replace the intense outrage felt at the war’s onset. Some decide to abstain from the news in the interest of “self-care,” while “compassion fatigue” has advanced from pop psychology to become the subject of serious study, with a campaign underway to rename it “empathic stress fatigue.” Indeed, the term “empathy” seems more accurate when describing the physiological trait by which we experience the suffering of others through the same subgroups of neurons firing in the brains of those afflicted—when our bodies actually feel a physical echo of another person’s pain—while “compassion” becomes a deliberate moral decision on the part of the observer. Either way, a moment seems to arrive when people cease to identify with the suffering individual, when morality breaks down and a fear for their own fate replaces the fate of those experiencing danger directly, when—somewhat farther down the path of desensitization—a desire to help eventually gives way to boredom and cynicism. As Susan Sontag observed in Regarding the Pain of Others, “compassion is an unstable emotion. It needs to be translated into action, or it withers.” Although our horror at distressing events fed to us through the media diminishes over time, and we find ourselves grappling with the moral dimensions of this phenomenon, for the individuals directly affected, as the reality of what is happening to them remains, independently of our perception—or the recognition of our own implication in the injustice being perpetrated on them—just as immediate, dire, and deserving of our urgent attention and action. As Sontag explains, we need “to set aside the sympathy we extend to others beset by war and murderous politics for a reflection on how our privileges are located on the same map as their suffering, and may—in ways we might prefer not to imagine—be linked to their suffering [. . .].”

Immanuel Kant regarded the cultivation of compassion as a moral obligation. More than a century prior to the wider dissemination of photography in illustrated news journals and a full two centuries before the rise of the internet and the information explosion, he understood the ways in which outrage and empathy became dulled by continuous exposure. Consequently, he sought to replace mutable, hence unreliable human emotion with an imperative based entirely on reason and calling for the active and disciplined fulfillment of one’s moral duty toward others. For now, our sleep is uneasy as we grapple with our conscience and our inertia, yet how much more jarring and cruel the return to the waking state must be each day under siege, when, as Simone Weil describes in “The Iliad, or the Poem of Force,” “the mind is then strung up to a pitch it can only stand for a short time; but each new dawn reintroduces the same necessity.” I thought of the tormented expression on the face of one of the sculptures Michelangelo completed for the Medici tombs in the New Sacristy flanking the Basilica of San Lorenzo, as the mind, still heavy with sleep, rouses to grasp that it is once again losing its refuge in dreams and the limbs gather slowly to bring the body into an upright position, and thought of people waking each day to the reality of gunfire, bombs, crowded shelters, and imminent flight. Buonarotti believed the soul was closer to its source in sleep; how the people of Ukraine can bear this return to the physical world each day and where they find the courage to continue living is something I wonder about when the alarm rings and I pull the blanket up over my eyes for a brief reprieve as I sift through the last shreds of a dissipating dream before facing the coming day.

***

© 2022 Andrea Scrima. All Rights Reserved.

Information on Andrea Scrima’s first novel, A Lesser Day, can be found here.

Her second novel, Like Lips, Like Skins, was published Sept. 2021 in a German edition titled Kreisläufe. English-language excerpts have appeared in Trafika Europe, Statorec, and Zyzzyva.