by Mike O’Brien

“Would that I did not have to speak!” —Confucius, Analects 17:19

Some writers are cursed with the belief that they have something uniquely important to share with the world, and that they must toil in order to make this special gift known to the world. I am free of such a terrible burden. But I know that if I didn’t write, I would simply degenerate and revolve around my own private mental drain-holes, so I hitch myself to writing obligations such as this one. It seems to be working out. I do, however, get the occasional twinge to write about the things that most bedevil my mind, whether or not I believe that anything good will come of it. These are, chiefly, the inevitable and hastening collapse of “normal” climate patterns (and the ecosystems dependent on them), and the perhaps not inevitable but certainly hastening march of lawless fascism in the United States. These two issues grip me like no others, because I live on Earth and, more precisely, above the United States. I don’t think that I have the power to ameliorate either situation by concatenation of the right sequence of letters. But I do feel an itch to see my feelings about these catastrophes put into words outside of my own head. Maybe as an affirmation of my own internal experience, maybe out of some duty to witness and to testify.

I shy away from indulging this impulse because I don’t want to bore people, or to further depress myself. I suppose this is a failure to believe in the entertaining power of my own writing, because when I read other writers’ work on these subjects I am not bored (and only a little more depressed), but rather absorbed and incensed. Some months ago I found a writer whose concerns and attitudes almost completely echoed my own in the bleak realms of empire, environment and global existential hurtling.

I recently revisited his page and was struck again by the kindredness of not only his views but also elements of his history. We are different enough superficially, he currently residing in Sri Lanka, with considerably more travelling and living to his name, but he strikes me as a soul brother of sorts. So, I feel somewhat relieved of the obligation, or compulsion, or whatever damned daemon it is that prods me to pronounce on the smouldering, radioactive prison barge that we 8 billion wretches call home. Instead, I suggest you just read Indrajit Samarajiva’s work (indica.medium.com). He is right about everything. I also lifted my Confucius quote from an article of his entitled “At Least It’s A Good Time For Philosophy”. Alright, maybe he’s not right about everything.

A long time ago, I either read or read of (after years of bullshitting my way through school, it is hard to discern what I know and what I merely know of) a speech by William James entitled “The Moral Equivalent of War”. I encountered it back in the 1990’s, when the biggest problems my youthful suburban self could imagine was civilizational degeneration as a result of too much peace. Thank goodness that threat never materialized. James’ idea was that, with the coming pacification of the world, some form of collective service was required to stiffen backbones and sharpen minds, lest the Western world become a soft mass of indulgent individualism, ripe for picking by peoples who had maintained their martial mettle (a California-annexing Imperial Japan was his particular example).

Some of his exhortations still resonate; diminish economic selfishness and inequality, reorient the production away from wasteful indulgence, make civic service and investment a point of individual and national pride. Some other elements of James’ argument aged badly. He delivered his address after the Boer and Spanish-American wars, but before the First World War, so it is easy to scoff at his optimism that war would become so scarce as to require a replacement. His employment of racial essentialisms and characterization of feminism as a cause and symptom of civilizational weakness were not exceptional but still stain the piece. The most tinfoil-chewingly jarring bit for an eco-pinko like myself, however, lies in perhaps the central claim in the whole speech: that, so as not to waste away in peace, we require “a conscription of the whole youthful population to form for a certain number of years a part of the army enlisted against Nature…”. To be charitable to James, “Nature” could be understood at least partly as our state of vulnerability, of exposure to danger and to want. But the domineering quality of this approach to Nature is not excused by its humanitarian motivations.

Matters of War and Peace have been on my mind lately, having recently finished Tolstoy’s novel bearing that title. It only took two years. I feel obliged to admit that I experienced it via audio-book, which probably required more time and attention than my own darting eyes would have taken. It was full of happy and instructive surprises, not least among them: how much self-indulgence an author can permit himself when he knows the measure of his mastery. The novel is looong and deliberate; if I had disliked it I would say “plodding”, but since I liked it quite a bit, I say “deliberate”. It is interspersed with Tolstoy’s own opinions on the practice of war and of history, occasioned by the historical events in the story, which is fine. But after the end of his characters’ narrative arcs, the author appended two (two!) multi-chapter epilogues, consisting of his theories on the practice and study of war, and of history, and of the soul of Man in general. It’s his book, he can do what he wants with it. And in the eras before YouTube and pocketable video games, I imagine people were quite glad to have more pages with which to pass the time rather than less.

One of Tolstoy’s pet theories was that the “humanization” and legal domestication of warfare was a dangerous error, because it would make war more palatable, more easily integrated into the normal order of affairs, and thereby make it easier to initiate and to continue. Better, his reasoning goes, that it remain as horrible and as scandalous as possible, an unholy affront to law and to humanity, and by that monstrous character better compel humanity to avoid it. This is an idea that many other people have expressed. The inventors of some of history’s most destructive weapons publicly claimed that their inventions would end war by making it too horrible to countenance. Their imagination concerning human brutality evidently lagged behind their technical ingenuity.

Poking around the internet, I learned that Tolstoy’s idea has been much discussed among legal and military theorists, and nowadays it is considered plausible but dis-proven by the results of various conventions limiting warfare, the Geneva Convention being the most well known. I wonder, though, whether that judgment is premature. It is an empirical question whether the legal and socio-political domestication of war will make it more or less frequent and destructive. How much data is enough? Which instances are reflective of the normal trend, and which are aberrations? Let us remember that, in the age of nuclear weapons, the consequences of a single conflict could outweigh those of all previous wars combined. If a mitigation strategy worsens all conventional wars but prevents a single nuclear one, it may be the greatest salvation ever bestowed upon the world. And if it has the opposite effect, well, that’s the end of all that, I suppose.

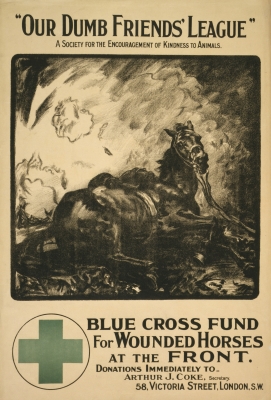

I experienced an unexpected virage in all this talk of humanitarian efforts and military restraint, into the field of animal welfare, a field which frankly interests me infinitely more than the murderous squabblings of humanity. This is not so odd, as Tolstoy himself advocated vegetarianism as well as pacifism. The hook came as I was listening to an episode of “The Animal Turn”, an animal ethics podcast created by Queen’s University’s A.P.P.L.E. project (short for “Animals in Philosophy, Politics, Law and Ethics”). The guest was Dr. Saskia Stucki, a research fellow at the Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law. She was speaking about the distinction between animal rights and animal welfare, discussed at length in her recent paper “Beyond Animal Warfare Law”. The gist of it is that international humanitarian law (as applied in warfare) parallels animal welfare laws in this important respect: neither accords their protected subjects (combatants and animals) a right to life, or any other such rights as human persons enjoy in peacetime. While international humanitarian law (IHL) seeks to mitigate harms, it still treats combatants as valid targets of injury and death, and qualifies its calls for protection with deference to military necessities. That is to say, it exhorts actors in conflict to kill and main as little as possible while they pursue objectives achievable chiefly by killing and maiming. We already know what Tolstoy would say of this.

Of course, such a legal regime is a backstop against even worse conduct, and it is understood that war is an aberration from the normal case wherein people enjoy (supposedly) inviolable rights to life and bodily integrity, among other peacetime niceties. The contrast between the human and animal cases is that animals enjoy only the worst-case mitigation regime, operating under the assumption that they are all valid targets of injury and killing. They have no peace to return to, and they have no rights to regain. Just as the military necessity of seizing a town justifies the killing of the soldiers defending it, but not their torture or execution after surrendering, the economic necessity of turning animals into goods justifies their confinement and slaughter, but not in a manner that is “excessive” or “abusive”. And so some 70 billion animals (excluding marine animals, about whom the estimates are murkier) are killed annually without any “wrong” done. But let us spare a moment to cluck our tongues at stories of pets abandoned in Ukraine.

Stucki addresses concerns that animal welfare law legitimates the “war” on animals by cooperating with exploitative animal industries and granting them some compromise, drawing a line between, as she puts it, “necessary unnecessary suffering” and “unnecessary necessary suffering”. This tension between ideal and pragmatic ethical concerns is rife throughout animal ethics, given the mind-boggling magnitude and severity of harm to be addressed. It would, all things being equal, be best to enshrine and enforce robust rights for animals as soon as possible, while mitigating their suffering as much as possible with welfare protections in the interim. But all things are not equal, and it is reasonable to expect that reforms which make the intolerable less intolerable will thereby salve the public conscience and forestall abolition. It is helpful to remember that animal protection activists are not homogeneous or perfectly coordinated (to put it mildly), and so questions of which path they ought to unanimously endorse are moot. The abolitionist purists can forswear all “collaborationist” welfare reforms, and a lot of welfare reform work will still get done (hopefully) by the more pragmatically oriented activists.

If things really start to get dicey for, e.g. meat-raising operations (dicier than their current situation, which is operating zoonotic disease factories in the middle of a global viral pandemic), they may welcome highly visible animal welfare reforms as a way to re-establish their social license to operate. It is similar to calls from energy and energy-adjacent industries for governments to establish clear carbon pricing regimes; the far-sighted among those companies realize that it is prudent to trade some short-term profits for a reaffirmed right to exist. Whether such rights would prevail over the existence rights of forests, or whales, or healthy humans is another question (my magic 8-ball says signs point to yes).

Stucki proposes parallel concepts for wartime humanitarian law (jus in bello), human rights, and laws regarding the initiation and cessation of war (jus ad/contra bellum). These concepts would be animal welfare law (already widely implemented, whatever its vicissitudes), animal rights (still largely unrecognized, and even less so enforced), and laws regarding the permission/abolition of animal exploitation (ending the “war” on animals, and circumscribing conditions under which it may be permitted out of necessity). The question of whether the “war” deserves any legitimacy within law remains, as does the question of whether laws which permit such a “war” should constrain the conscience of those who value the welfare and rights of animals.

I see some value in Stucki’s positing the “jus contra exploitation” as a missing link between “wartime” animal welfare protections and “peacetime” animal rights. But several profound dis-analogies trouble this framing, as pointed out by Tom Regan and other thinkers cited in her voluminous and enlightening footnotes. Two of his main objections are that war is about destroying, while animal exploitation is about profitable rendering; and while war in the era of humanitarian laws is chiefly the business of states, animal exploitation industries are more analogous to mercenaries. I hope to explore these objections and possible re-framings further in my next instalment, if we’re all still alive in two months.