by Joseph Roth (translated and adapted by Rafaël Newman)

Every now and then, a nation becomes modern. Greeks and Poles and Russians were modern, for a time. Now it’s the Ukrainians’ turn.

Every now and then, a nation becomes modern. Greeks and Poles and Russians were modern, for a time. Now it’s the Ukrainians’ turn.

The Ukrainians, about whom we and the rest of the Western world know little more than that they reside somewhere between the Caucasus and the Carpathians, in a land of steppes and swamps, and that the Ukrainian leg of our junket was relatively pleasant on account of the increased per diem for the duration of the trip. We also have an exceptionally fuzzy notion of a “Ukrainian peace for bread,” owed to the political dilettantism of an Austrian military diplomat.1 Otherwise, “Ukrainians” are among those peoples who cannot definitively be declared mere cannibals—or worse, illiterate cannibals. Judging by their origins, at any rate, they must certainly be “Russians or the like,” and, by their faith, primitive Catholic heathens, whose clergy is all flowing beards, gold, frankincense, and myrrh.

Such operetta commonplaces concerning a country and its people are all too seductive. The Poles have already been excessively Westernized, and we even have more precise information now about the Greeks, ever since Mitteleuropa learned that Greek monarchs and film starlets are equally susceptible to monkey bites.2 Russia itself has become a familiar concept, thanks to all the German émigrés and POWs, so it’s no longer of any use for cabaret and operetta. What’s left?

Ukraine.

An impoverished Jewish immigrant from Lublin (in what was once known as Congress Poland3) opens a tobacconist’s in the east end of Berlin, scribbles a few Cyrillic characters on a sign, and claims his shop is “authentically Ukrainian.” Girls twirl to the latest American jazz in coffee houses and call it a “Ukrainian folk dance.” Most modern of all, however, are the “Ukrainian” pantomimes and ballets.

Berlin is wallowing in grotesque operetta Ukrainianism. Any melody with the least Slavic timbre is dubbed “Ukrainian.” To be sure, the genuine Ukrainians have themselves given rise to this fashion, by way of the Ukrainian choirs that have performed here, as in several major European cities, frequently and to enormous acclaim, and which have offered a general lesson in the economics of making money from a national and political idea. Furthermore, the situation in Eastern Europe means that Russians and Ukrainians and Poles are all on the move westward, where they are all becoming “Ukrainians,” since “Ukrainian” happens to be the fashion of the day.

As a result, the “Ukrainian” ballets are a regular mishmash: a bit of Tartar, a bit of Russian, and a little Cossack as well, to be fair. After all, it is the duty of vaudeville troupes, to whom this article is addressed, to entertain, and not to pursue academic research in ethnology. But one ought not denature national culture; certainly not the culture of a currently defenseless people, whom Bolsheviks and Poles have robbed of its homeland.

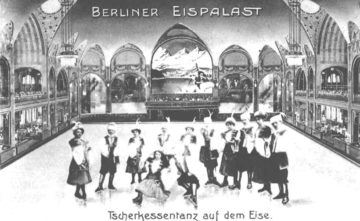

The Eispalast, whose ballet corps boasts top-flight training and where true artistry may be admired, is showing “The Red Shoes,” a ballet pantomime.4 This purports to be a Ukrainian legend. The church at the back of the stage set is not Ukrainian (that is, Greek Catholic), but Russian (that is, Orthodox). The lead ballerina sports the Russian headdress—Ukrainian women wear only flowers in their hair, white blouses with blue and red ornaments on the sleeves and borders, never silken jackets with gold braiding. Ukraine has never been home to the Circassians, who come from the Caucasus. Ukrainian peasant women wear low boots, never white dancing slippers. With the exception of a so-called “Hoppaks” and a “Kolomejka,” the dances are all Russian.

The Eispalast, whose ballet corps boasts top-flight training and where true artistry may be admired, is showing “The Red Shoes,” a ballet pantomime.4 This purports to be a Ukrainian legend. The church at the back of the stage set is not Ukrainian (that is, Greek Catholic), but Russian (that is, Orthodox). The lead ballerina sports the Russian headdress—Ukrainian women wear only flowers in their hair, white blouses with blue and red ornaments on the sleeves and borders, never silken jackets with gold braiding. Ukraine has never been home to the Circassians, who come from the Caucasus. Ukrainian peasant women wear low boots, never white dancing slippers. With the exception of a so-called “Hoppaks” and a “Kolomejka,” the dances are all Russian.

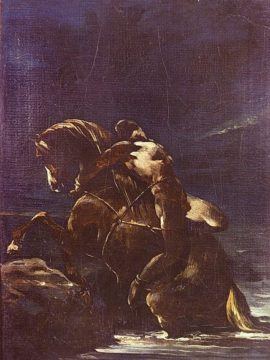

The story of the Ukrainian Cossack hero and rebel Mazeppa, whom, as we know from the annals, the Polish king caused to be bound naked to the back of a horse and dragged for several days across the Ukrainian steppe, can be enjoyed at the Circus Sarrasani.5 Here too, Russian motifs have found their way into Ukrainian national history. Ukrainian clerics are Greek Catholic and do not wear patriarchal beards.

Glazeroff’s Ukrainian ballet is Ukrainian, but it overdoes its Ukrainianness and performs its dances—with knives, Indian style.6 These are absolutely capital dancers from Kyiv who feel obliged to play the “savage” for their western public, for whom a Kolomejka is too tame, considering the cost of a ticket. Ukrainians have never once danced with knives in their mouths.

The Ukrainian national culture is sui generis, distinguished by clear national characteristics, and has nothing in common with its Russian or Polish or Tartar counterparts. But the phenomenon as such is interesting: the fact that a nation, once it has lost its political independence, immediately begins to prevail in operettas and cabarets.

- The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was a separate peace signed in February 1918 between the Central Powers and the newly formed Ukrainian People’s Republic. Known in German as the Brotfrieden or “bread for peace,” because it was intended to supply the Austro-Hungarian Dual Monarchy with badly needed grain, it was negotiated by Ottokar Czernin, Roth’s “Austrian military diplomat.”

- King Alexander, who ascended to the Greek throne in June 1917, succumbed to sepsis in October 1920 following a bite from a macaque.

- Also known as “Russian Poland,” formed at the Congress of Vienna in 1815 as a semi-autonomous successor to Napoleon’s Duchy of Warsaw and in existence, under de facto Czarist control, until Polish independence following World War One.

- The Eispalast was a multipurpose sport and amusement venue in Berlin’s Schöneberg district, in existence from 1908 until its destruction in 1943.

- Ivan Stepanovych Mazeppa (c. 1639-1709) was the hetman, or leader, of Cossack-controlled Ukraine who joined the Swedes to fight the Russians in the early 1700s. He is the subject of a poem by Lord Byron (1818). The Circus Sarrasani, created in Germany at the turn of the 20th century by Hans Stosch, was celebrated throughout the Weimar Era and into the Third Reich; it was destroyed during bombing raids in 1945.

- Senin Glazeroff, born Salomon Abramovich Glazer (1882-1944), performed “authentic” folk dances with his wildly popular troupe during the Weimar Era; he was proscribed by the Nazis following their accession to power and died in exile.

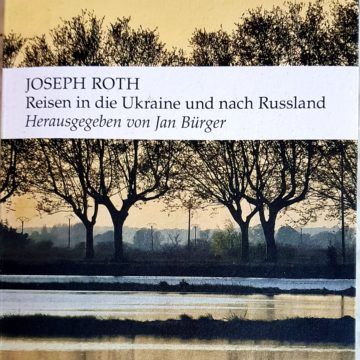

Joseph Roth (1894-1939) was born in Brody, now Ukraine, in what was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire, studied in Lviv and Vienna, worked in Berlin, and died in Paris. Famed as a novelist for such works as Hiob (1930), a New World retelling of the Biblical Book of Job, and Radetzkymarsch (1932), his magnificent farewell to the Habsburgs, Roth also worked as a journalist, publishing accounts of his travels in an Eastern Europe in the process of transformation following the Great War, the Bolshevik Revolution, and the collapse of “multinational” empires. The piece posted here, translated and adapted by RN, originally appeared in the noon edition of the Neue Berliner Zeitung newspaper on December 13, 1920; it was republished in 2015 in a collection of Roth’s articles on Ukraine and Russia edited by Jan Bürger, and reissued in a sixth edition in 2022.

Joseph Roth (1894-1939) was born in Brody, now Ukraine, in what was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire, studied in Lviv and Vienna, worked in Berlin, and died in Paris. Famed as a novelist for such works as Hiob (1930), a New World retelling of the Biblical Book of Job, and Radetzkymarsch (1932), his magnificent farewell to the Habsburgs, Roth also worked as a journalist, publishing accounts of his travels in an Eastern Europe in the process of transformation following the Great War, the Bolshevik Revolution, and the collapse of “multinational” empires. The piece posted here, translated and adapted by RN, originally appeared in the noon edition of the Neue Berliner Zeitung newspaper on December 13, 1920; it was republished in 2015 in a collection of Roth’s articles on Ukraine and Russia edited by Jan Bürger, and reissued in a sixth edition in 2022.

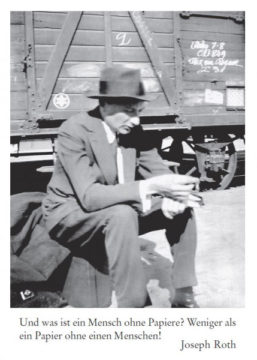

In a preface to the 1937 edition of Juden auf Wanderschaft (first published in 1927), his essay on the contemporary vicissitudes of Eastern European Jewish life and the fates of emigrants to the West, Roth, by then himself living as an exile in Paris, formulated the dilemma of the forced migrant in an often-cited aphorism:

In a preface to the 1937 edition of Juden auf Wanderschaft (first published in 1927), his essay on the contemporary vicissitudes of Eastern European Jewish life and the fates of emigrants to the West, Roth, by then himself living as an exile in Paris, formulated the dilemma of the forced migrant in an often-cited aphorism:

And what is a person with no papers? Less than a paper with no person!