by Leanne Ogasawara

Stanley Tucci begins his hit TV show Stanley Tucci: Searching for Italy, by reminding us that, yes, he is Stanley Tucci. But perhaps more importantly, that he is “Italian on both sides.”

Yeah, yeah, I thought I was Italian too.

Life was so much easier before DNA testing. I mean, in the good old days you could just make up any old story about your family heritage –and who was anyone to contradict you? Seriously, if you told people you were Italian, then you were Italian. Finito. And I actually do have Italian blood. On my grandmother’s side. My grandma’s grandparents on both sides came from Calabria, on the Italian peninsula near the toe of the boot. They could practically see Sicily.

That is where both sides of Tucci’s heritage comes from too. I never realized until recently how many Calabrese found their way to the United States. A huge percentage of all Italian-Americans are Calabrese.

Like Tucci, I even knew their names: Tripodi (classic Calabrese name) for one great-grandparent and Pelicano for the other. Sounds pretty Italian to me.

Never mind that every time I proudly told an Italian from Rome or Milan about my Calabrese heritage they seemed to be stifling the impulse to laugh.

And never mind that I also must have Irish blood in equal portions.

Or so I thought. Read more »

I had a colleague, a great reader, whose favorite material was mid-century Japanese short-form realism. Frequently epistolary and often featuring at least one frame narrative, these novellas typically have as their narrator someone captivated, not to say obsessed, by a memory; and that memory, it seemed to me when I read the works my colleague lent me, is almost inevitably fed by an erotic or romantic encounter, as well as by its often calamitous sequelae.

I had a colleague, a great reader, whose favorite material was mid-century Japanese short-form realism. Frequently epistolary and often featuring at least one frame narrative, these novellas typically have as their narrator someone captivated, not to say obsessed, by a memory; and that memory, it seemed to me when I read the works my colleague lent me, is almost inevitably fed by an erotic or romantic encounter, as well as by its often calamitous sequelae.

In the early 1980’s apart from joining the September group, there were two other outside organizations I was invited to join which expanded my intellectual horizons. The first was the South Asia Committee of the Social Science Research Council in New York. This Committee planned some research projects on different topics of social science in South Asia and also gave out research fellowships and postdoctoral research grants. It gave me the opportunity to interact with some of the top scholars working in the US on South Asia, including Myron Weiner, the distinguished political scientist, Bernard Cohn, the historical anthropologist, Wendy Doniger, the Sanskrit scholar, Ralph Nicholas, cultural anthropologist of Bengal, Richard Eaton, cultural historian of medieval India, and Ronald Herring, political scientist on agrarian development in India.

In the early 1980’s apart from joining the September group, there were two other outside organizations I was invited to join which expanded my intellectual horizons. The first was the South Asia Committee of the Social Science Research Council in New York. This Committee planned some research projects on different topics of social science in South Asia and also gave out research fellowships and postdoctoral research grants. It gave me the opportunity to interact with some of the top scholars working in the US on South Asia, including Myron Weiner, the distinguished political scientist, Bernard Cohn, the historical anthropologist, Wendy Doniger, the Sanskrit scholar, Ralph Nicholas, cultural anthropologist of Bengal, Richard Eaton, cultural historian of medieval India, and Ronald Herring, political scientist on agrarian development in India.

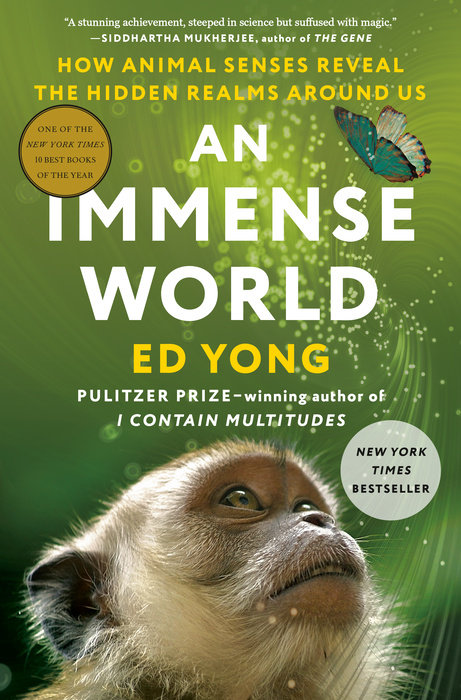

An Immense World; How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us, Ed Yong, Random House/Bodley Head, June 2022

An Immense World; How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us, Ed Yong, Random House/Bodley Head, June 2022

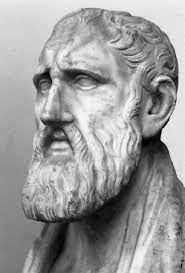

One of the more remarkable developments in popular philosophy over the past 20 years is the rebirth of stoicism. Stoicism was an ancient Greek and Roman philosophy founded around 300 BCE by the merchant Zeno of Citium, in what is now Cyprus. Although, contemporary professional philosophers occasionally discuss Stoicism as a form of virtue ethics, most consider it to be a minor philosophical movement in the history of philosophy with limited influence. Yet it has captured the attention of the non-professional philosophical world with many websites and online communities devoted to its practice.

One of the more remarkable developments in popular philosophy over the past 20 years is the rebirth of stoicism. Stoicism was an ancient Greek and Roman philosophy founded around 300 BCE by the merchant Zeno of Citium, in what is now Cyprus. Although, contemporary professional philosophers occasionally discuss Stoicism as a form of virtue ethics, most consider it to be a minor philosophical movement in the history of philosophy with limited influence. Yet it has captured the attention of the non-professional philosophical world with many websites and online communities devoted to its practice.  Sughra Raza. Be Unvaan. June 11, 2022, Cambridge, MA.

Sughra Raza. Be Unvaan. June 11, 2022, Cambridge, MA.

Thomas O’Dwyer, my husband, died on Wednesday. He wouldn’t approve of this beginning. In his articles he always came up with something original or intriguing to draw the reader in.

Thomas O’Dwyer, my husband, died on Wednesday. He wouldn’t approve of this beginning. In his articles he always came up with something original or intriguing to draw the reader in.

“Thus the concept of a cause is nothing other than a synthesis (of that which follows in the temporal series with other appearances)

“Thus the concept of a cause is nothing other than a synthesis (of that which follows in the temporal series with other appearances)