by Bill Murray

In this column I write about international travel, especially travel to less understood parts of the world. This month, with such travel still a wee bit constrained, we start a two-part look back at Sri Lanka, April/May 1999:

There are certain things a guidebook ought to level with you about right up front, before gushing about the exotic culture, pristine sandy beaches and friendly people. Number one, page one, straight flat out:

YOU ARE FLYING INTO A COUNTRY THAT CAN’T KEEP THE ROAD TO ITS ONE INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT PAVED, AND LINES THE ROAD IN AND OUT WITH BOYS WITH NO FACIAL HAIR HOLDING MACHINE GUNS.

Lurching into and out of potholes on the road from the airport to the beach, dim yellow headlights illuminated scrawny street dogs sneering from the road, teeth in road kill. Mirja and I took the diplomatic approach and decided, let’s see what it looks like in the morning.

•••••

The fishing fleet already trolled off the Negombo shore in the gray before dawn. The last tardy catamaran, sail full-billowed, flew out to join the rest.

Sheldon had already been out and back. A slight fellow, just chest high, with a broad smile under a tight-clipped mustache, Sheldon showed me his catch, in a crate, a few gross of five or six inch mackerels.

He took me to meet all the other guys and see their catches, too, stepping over nets they were busy untangling and setting right for the afternoon. He led me to his house, just alongside and between a couple of beach hotels, shoreside from the road, among a sprawl of a dozen thatch huts.

Sheldon built it himself. It was before the 2004 Boxing Day tsunami and I don’t know if it, or Sheldon and his family, are there anymore. He took me inside, immensely proud, to show me how he had arranged two hundred woven palm-frond panels on top of one another to build the roof. He told me “two hundred” over and over.

A thatch wall divided Sheldon’s house into two rooms. The only furniture was a rough wooden bed with no linens.

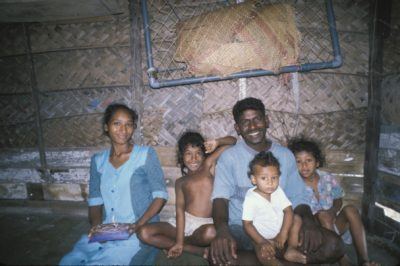

Sheldon’s wife, a very young woman dressed in a long blue and white smock with her hair pulled back, rose with a smile to greet me, and their precocious four and six year old daughters danced around us all. Sheldon took his son, just one year old, into his lap as we talked.

We sat together near a crack in the wall where sunlight came through so they could look at postcards of where I was from. They served sweet tea. I drank it fearing I’d pay for drinking the water later that day.

Sheldon walked me back toward Hotel Royal Oceanic, two hundred meters and several worlds apart. On the way, he explained to me that he was 31, his brother was “41, 42 sometimes. Lives nearby, Mama too. Papa no.”

•••••

I’d plotted a Sri Lanka itinerary twice too ambitious. The roads were fine, really. There were just too many people trying to use them. The two lanes couldn’t cope with the mass of people and machines vying for them.

If you weren’t on a highway, or were at a sharp bend in one, you’d have to stop to let bigger vehicles squeeze by. And since there were no bypass roads for heavy trucks, and since most folks didn’t have private cars but instead rode big, fat inter-city buses, you were forever stopping and starting and squeezing between milk trucks and cement mixers and buses, and in Sri Lanka there were also tuk-tuks, those three-wheeled two-stroke vehicles used from Bombay to Bangkok to Borneo.

So we stopped for every bus. Our driver Tyrone joked about having to stop for women drivers, too. Our air conditioner “work very good, sir.” That was a damn good thing on the coastal plain where, as we passed a cricket match at 10:15 in the morning, I thought them all positively fools, running around in long pants.

•••••

Provincial elections were to be held the next day. Election posters covered the buildings. Tyrone claimed 99% literacy in Sri Lanka (other sources suggested 90 per cent), but even so they used a system like in much less literate Nepal. Each party was represented by a symbol, so that the illiterate could recognize their party and vote, in this case, for “chair” or “elephant” or “table” or “bell.”

The main parties were the ruling Sri Lanka Freedom Party, in power for the last five years and advertised by posters of the president, Chandrika Kumaratunga, holding her hand high in the air, and the opposition United National Party, which had held power the prior seventeen years.

Plastic flags flew over the road like over a used car lot. Blue marked the incumbent party’s territory, green the challengers’. By the plastic flag test, it would be the Freedom Party in a romp.

In a tradition of pre-election violence, a couple of weeks ago a woman blew herself up in Colombo. And a few years ago, days before a visit by Prince Charles, eight were killed near the Buddha’s tooth shrine in Kandy, the second city and seat of power under the ancient kings.

Tyrone offered that, “I will be gathering information,” about potential trouble. This morning’s news was that a candidate in the east had been shot overnight. Yesterday was the last day of electioneering, with no rallies allowed from then.

That kind of violence baffled him, Tyrone said, and anyway it doesn’t matter which party rules – they both promise the world until elected and then they don’t do anything.

Some things are the same the world over.

He was puzzled why people took it all so seriously, he told us, when the leaders themselves don’t; At the end of the day, he said, they sit down and “they have a drink together.”

•••••

The wealthier houses presented whitewashed concrete walls to the road. Those funny-looking pointy-nosed one-cylinder “rototiller” tractors like they use in rural China were here, too.

Coconut plantations dominated the road to the main Colombo-Kandy highway. Bicycle carts pedaled by, some with wooden baskets built on back and scales cradled inside. Rolling, mobile merchants. Tyrone showed us a motorcycle with a box of little fish and said the guy goes door to door. Banana trees along the road, underneath tall coconut palms.

Everything grew here, I guessed. Mangoes were in season now, and avocados. Durians were out of season but they grew here, too. Tyrone called them the fruit that tastes like heaven but smells like hell.

Tyrone had fifteen years in the business and looked for all the world like a wiry, Sri Lankan Jeff Goldblum. He was good. He wasn’t a young, adventurous boy-driver. He was comfortable in himself. He told us not too many Americans came here and we could see that.

Germans, Italians, Japanese and British came, but really it was mostly the Germans, with their big charter airline LTU discharging a crew at the hotel as we left, and copies of Bild, Bild Frau magazines and cheap German novels and crossword books lying around the lobby coffee tables.

•••••

We got the Kandy road and suddenly Tyrone got politics. He liked the Freedom party because they were pro-privatization. They one hundred percent privatized the tea plantations, for example. He couldn’t cite a lot of other differences except the opposition was more socialist.

He guided us through a tangled story of ruling families and power politics that left me way behind. Sometimes he lapsed into tour-guidism (“Excluding inland waters, area of Sri Lanka is 65,000 square kilometers.”).

The Kandy road was wide enough for two cars to pass side by side. As we began to bite off a little elevation en route to Kegalle, Tyrone returned to practical matters surrounding the elections. There would be a curfew, he thought, tomorrow night as the election results came in, and it would most likely last for 24 hours.

That suggested possible violence, I thought, but it seemed normal to Tyrone, and it came with a benefit. We could get a “special travel permit,” and with the road less busy, “we can go ninety hundred,” he laughed.

Kegalle was stifling hot and gridlocked with buses and tuk-tuks in both directions. Traffic police stood surrounded by the chaos and did no good that I could tell. It reminded me of the garrison town of Wangdi Phodrang in Bhutan, about which Barbara Crossette wrote, “welcoming, but exceptionally unappealing.”

Four kilometers past Kegalle, a road sign: “A home for domesticated, disabled and elderly elephants.” We swung left into the elephant orphanage at Pinnawala.

All these elephants had become separated from their families in the national parks or in the wild; Maybe their families were shot for their tusks, for example. One had his right front foot blown off by a land mine.

Each elephant had his own individual trainer (there being no shortage of labor) and the trainers worked with their elephants all their lives. Asian elephants are trainable (we rode elephants in southern Nepal who would pick up logs, even trash, on their mahout’s command), but that doesn’t mean a trainer isn’t occasionally killed, especially during mating season.

You could get in quite close and mingle with the elephants. Kids petted a little one. It was humane that they cared for the elephants but, scruffy and indolent as all of the herd was, the whole scene was a little downbeat.

•••••

Seamlessly, spice country turned to tea country. Looking around, you could believe that Sri Lanka supplied the whole world. Boys played cricket in the road and they had to, because there were tea bushes utterly everywhere else.

Over the front seat, Tyrone was explaining how buffalo milk mixed with honey is the local equivalent of yogurt, when up came two signs, one explaining we’d achieved an elevation of 6187 feet, the other reading “Welcome to the Salubrious Climes of Nuwara Eliya.”

Straight through the scramble, at the far side of town stood the old British Grand Hotel. Nuwara Eliya (pronounced “Noo-relia”) is an old British hill station, full of well-tended proper English gardens and lingering British-built structures like the Grand Hotel – dark, wooden, rambling, musty and old.

It’s said that the Sinhalese preceded the Tamils to Ceylon and when the British arrived, the Sinhalese were unwilling to work for the slave wages the Brits wanted to pay. So the Brits recruited the Tamils and brought them up here to pick tea.

The good Tamils, as Tyrone called them, (not the trouble-causing Tamils agitating for independence) got housing, a stipend, a garden and a quota. After reaching quota they got a premium for the tea they picked, per kilo.

•••••

Six o’clock on election morning. Two loudspeakers chanted the call to prayer alongside a glass-enclosed Buddha statue just by the traffic circle. The sun hadn’t cleared the hills but it was set to be a glorious morning, with birds and dew run riot.

At this hour, Nuwara Eliya served mostly as a staging area for the bus station. People queued and a few stores lumbered open. At a milk bar (that’s a name for convenience stores, here to New Zealand) I bought toothpaste and remarked how it would be a nice day.

Dazzling smile: “It is election day, sir!”

END PART ONE