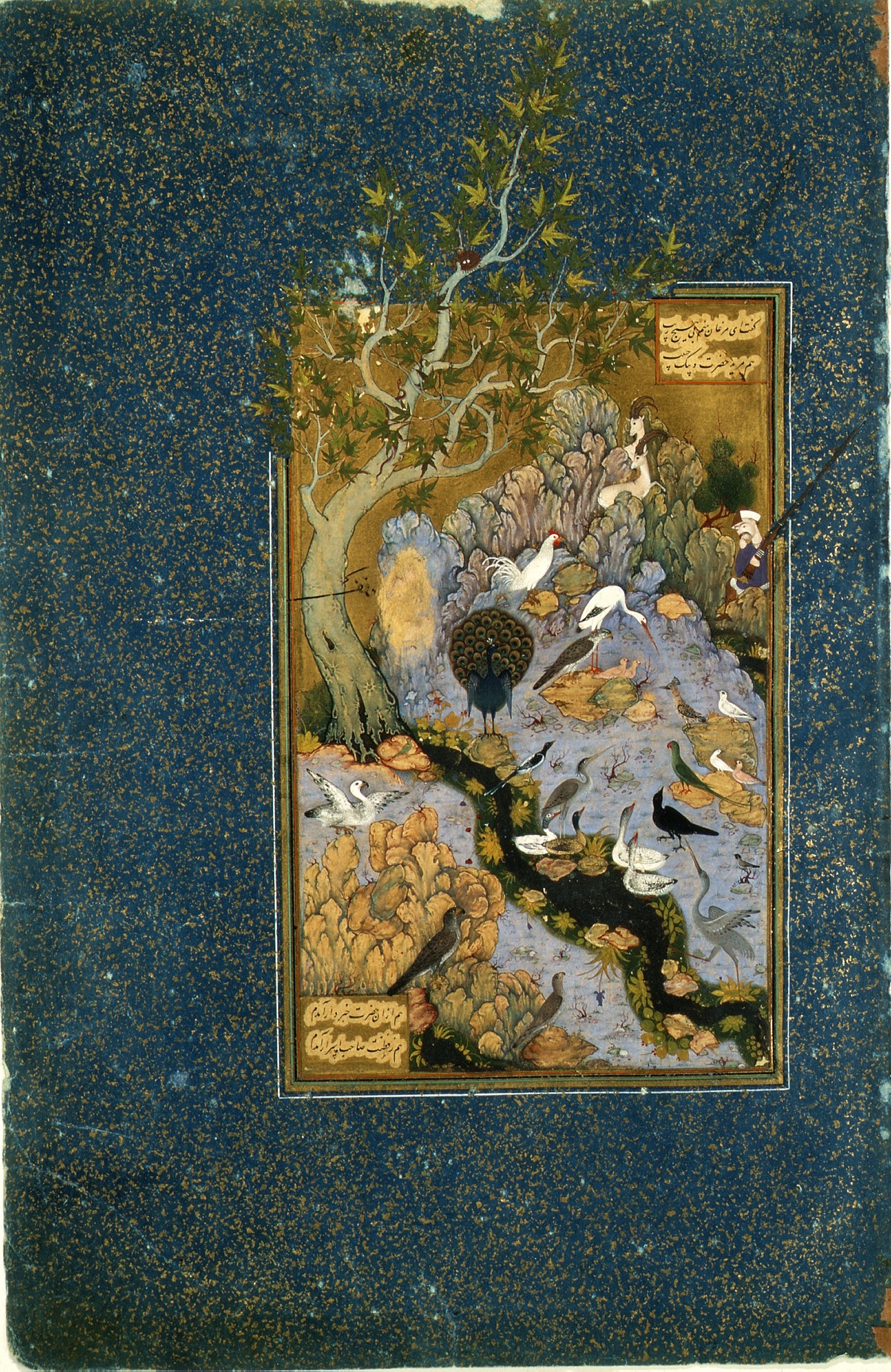

Habiballah of Sava. Concourse of The Birds, ca. 1600

Habiballah of Sava. Concourse of The Birds, ca. 1600

More here.

Habiballah of Sava. Concourse of The Birds, ca. 1600

Habiballah of Sava. Concourse of The Birds, ca. 1600

More here.

by Christopher Horner

Immanuel Kant is perhaps the most influential philosopher of modern times. His Critique of Pure Reason (1781) and Critique of Practical Reason (1788) famously investigated the the limits to human knowledge and the nature (as he saw it) of true morality respectively. But in 1790 he turns his attention to judgment, to what it is and what that implies, and what he says in The Critique of Judgment is interesting. Whether one agrees with him or not, what he has to say remains among the most suggestive and fascinating contributions to the question of what a judgment is. He discusses the way in which we find purpose and meaning in the world, the ‘sublime’ and much more, but my focus here is just on what he has to say about the judgment of beauty in nature and art, and to what extent we can find it convincing. Read more »

by David Oates

We sit in David Biespiel’s Republic Café: all of us together in the public space of democracy. It appeared in 2019, as American fascism made its perennial strut, less disguised than usual. At that point we’d endured two years of it. Lies spewed from the Leader’s mouth like flies from an open sewer, his followers enacting Hannah Arendt’s crisp formulation:

We sit in David Biespiel’s Republic Café: all of us together in the public space of democracy. It appeared in 2019, as American fascism made its perennial strut, less disguised than usual. At that point we’d endured two years of it. Lies spewed from the Leader’s mouth like flies from an open sewer, his followers enacting Hannah Arendt’s crisp formulation:

The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (i.e. the reality of experience) and the distinction between true and false (i.e. the standards of thought) no longer exist. (The Origins of Totalitarianism, 1951, p. 474)

It felt to me that Republic Café was the book we were waiting for, offering confirmation that I wasn’t crazy – that our politics really were (and are) that bad. And as a book of poetry, its honest eloquence offered evidence that good sense and good will were everywhere around us, too. I was joining an invisible multitude. Not a mob. A quiet quorum. A universal café.

Or we join with John Sibley Williams in the twilight of The Drowning House. A new book, two years after Biespiel’s. And once again comes that recognition: Yes, this is it. This is what it feels like.

Every poem is a crisis. It stands between the self and the world, between pleasure and pain, privacy and exposure, simplicity and extravagance. It attempts to make one small thing – a line, a moment, a metaphor – beautiful and coherent. When it fails, we hate it. (Hatred of poetry is a topic all unto itself!

It always fails eventually. But when it succeeds, we become believers. At least a little, briefly. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Eric Bies

In 1895, Ernest Hartley Coleridge published a volume of selections from his grandfather’s notebooks. Anima Poetae, the first such selection to be assembled, granted readers passage into the fantastic interior of the man, poet, and uncommon philosopher George Saintsbury would one day declare worthy of Aristotle and Longinus. Simply open the book onto any of its three hundred thrilling pages, and there shall be revealed the soul of the great Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Most fascinating among these revelations, perhaps, is the record of the poet’s reading. We learn, for instance, of his fondness for Milton and Swift—of his unfondness for Darwin and Hume. We learn that he puzzled (as Ezra Pound a century hence) over Duns Scotus and the Trinity, and that he was gobsmacked with the Germans: names like Kant, Fichte, and Schiller propagate like cacti. At one point we catch him privately praising the letters of Dorothy Wordsworth (“the best reading in the world”). Strikingly modern, we find he was a reader of dreams, too—his own often fitful, plaguing the waking hours—and even made some of them up:

If a man could pass through Paradise in a dream, and have a flower presented to him as a pledge that his soul had really been there, and if he found that flower in his hands when he awoke – Ay! and what then?

In the early nineteen-tens, the American scholar Jonathan Livingston Lowes undertook to mine the fullest possible spread of the notebooks. Combing through the archives of the British Museum and the Bristol Library, he herded his systematic record of the poet’s reading into one of the first great studies of the imagination. Upon its release in 1927, The Road to Xanadu drew admiration from every quarter. Readers could not help but to boggle at the rigor of its scholarship—painstaking literary detective work of the most rewarding type, as when Charles Olson crept through Melville’s marginalia and located all of that Shakespeare in Moby-Dick—much of which established the first key links between the books Coleridge perused and the poems he composed. Read more »

by Ethan Seavey

Breckenridge, Colorado: a village in the Rocky Mountains which is now known for its popular ski resort. Before 1859, it was a valley with a lush Blue River running through the crease by the foothills of the Ten Mile Range. In 1859, gold was first mined in Breckenridge. After 1859, over 5,000 white men (some estimate closer to 8,000) flocked to the valley, and the village sprung up quickly after.

Many of those men (for they were nearly all men) had stopped on their way home from the gold rush on the west coast, and others had come from out east. They had experience in mining, which not only meant knowledge of how to effectively collect the gold from the mountains, but that they knew how to survive in the isolated wilderness. In the 1860s, a gold miner from Breckenridge would earn about three dollars a day. Let’s make this clear: three dollars a day was a good amount of money. Many people across America were only earning a dollar, and others had no job. If being a miner didn’t pay well, no one would have come so far to work such a dangerous job. Every day, he would spend one dollar on his boarding, another on food and booze and an hour in a brothel, and send the third home to his family out east.

Mining meant stability at home (usually, back East) when work was hard to find. Still, they weren’t educated enough to learn that they were being cheated. The owner of the claim would take an average of ten dollars of gold from each of his men, every day. The owners lived in nice homes, and some of them never even laid their eyes on the mines. If you could afford it, you wouldn’t be living in Breckenridge. Read more »

by Pranab Bardhan

All of the articles in this series can be found here.

After my student days in Cambridge, in my professional life I have been to Britain many times, occasionally for lectures and conferences, but sometimes more formally on visiting assignments. The latter, except for the two terms at Trinity College, Cambridge, as a Visiting Fellow, have been more to Oxford and London School of Economics; this may be partly because for some time there was a relative decline in the quality of the Cambridge Economics Department after the internal troubles and the exit of some big names that I have alluded to before. In Oxford I have been on formal visits to All Souls College, St. Catherine’s College, and Nuffield College.

After my student days in Cambridge, in my professional life I have been to Britain many times, occasionally for lectures and conferences, but sometimes more formally on visiting assignments. The latter, except for the two terms at Trinity College, Cambridge, as a Visiting Fellow, have been more to Oxford and London School of Economics; this may be partly because for some time there was a relative decline in the quality of the Cambridge Economics Department after the internal troubles and the exit of some big names that I have alluded to before. In Oxford I have been on formal visits to All Souls College, St. Catherine’s College, and Nuffield College.

The first time in Oxford I was a Visiting Fellow at All Souls College in 1983. The occasion was an invitation to give a set of endowed lectures at the College, named after S. Radhakrishnan, who used to be a philosophy Professor and Fellow at the College, and later President of India. Amartya-da was then a Fellow at that College. I remember I arrived one afternoon straight from California and Amartya-da said he’d take me to dinner at College and explain the various quaint customs practiced in this College founded in 1438.

The College had no undergraduates and hardly any graduate students, only Fellows. I already knew that it had the reputation of being a Tory citadel and rather stodgy and rigid in its customs. After a great deal of contentious debate it admitted women only in 1979. I had also heard the story of the famous historian and Shakespeare scholar, A. L. Rowse, who at age 22 sat for the Prize Fellowship Examination at All Souls and did well in the written exam. But then there was another hurdle; he was invited to the dinner to check his table manners. At the end of the dinner pudding was served, and on top there was a cherry. Rowse did not know what’d be a proper way of disposing the cherry stone that was in his mouth. He pondered about alternative ways, but could not make up his mind, so he swallowed it. He did get the Fellowship, but even when he was past 90 years in age he told a journalist that he still had not figured out what was the proper way of tackling that stone at the All Souls dinner table in 1925. Read more »

by John Allen Paulos

The separation of church and state seems to be dissolving. It’s becoming increasingly easy for politicians and other public figures to cross the line between expressing their faith and aggressively proclaiming it and its alleged real-world consequences. Although often leading to social strife and intolerance, such overweening proclamations are growing in frequency. They may be cumulative and insidious like the Supreme Court’s recent okay for coaches to publicly pray at the 50-yard line after a game, or they may be all-out assaults such as GOP Congresswoman Lauren Boebert’s “I’m tired of this separation of church and state junk.”

Because religion and religious ideas are being so publicly professed, political candidates and others should get used to the free expression of doctrines contrary to their own, in particular to irreligious perspectives. People’s religiosity naturally invites questions about their beliefs and the reasons for them and these questions, I think, should be a bit more pointed than the usual softball queries about the role of faith in their lives.

Below are a few such questions that I would like to see directed to political candidates during debates or press conferences. You can imagine the attendant microphones and cameras, moderators and reporters. The questions may seem commonsensical to many, perhaps jejune to some, but I won’t hold my breath until one of them is asked. Read more »

by Charlie Huenemann

Today is July 4th, a day when Americans reflect on the value of freedom and the costs and sacrifices required for it. So it is an appropriate day to reflect on America’s deepest political aspirations.

Nah. Let’s talk about our brains. The neocortex is where all our fancy thinking takes place. The neocortex wraps around the core of our brain, and if you could carefully unwrap it and lay it flat it would be about the size of a dinner napkin, and about 3 millimeters thick. The neocortex consists of 150,000 cortical columns, which we might think of as separate processing units involving hundreds of thousands of neurons. According to research at Jeff Hawkins’ company Numenta (and as explained in his fascinating recent book, A Thousand Brains), these cortical columns are capable of modeling patches of our experience (he calls them “reference frames”) and setting our expectations of what we should experience next, at any given moment. [Note: the remarks that follow are inspired by Hawkins’ book, but shouldn’t be taken as a faithful representation of it.]

Nah. Let’s talk about our brains. The neocortex is where all our fancy thinking takes place. The neocortex wraps around the core of our brain, and if you could carefully unwrap it and lay it flat it would be about the size of a dinner napkin, and about 3 millimeters thick. The neocortex consists of 150,000 cortical columns, which we might think of as separate processing units involving hundreds of thousands of neurons. According to research at Jeff Hawkins’ company Numenta (and as explained in his fascinating recent book, A Thousand Brains), these cortical columns are capable of modeling patches of our experience (he calls them “reference frames”) and setting our expectations of what we should experience next, at any given moment. [Note: the remarks that follow are inspired by Hawkins’ book, but shouldn’t be taken as a faithful representation of it.]

The neocortex’s complexity is considerable, but not infinite, and what’s most surprising is that such a relatively small network—you can fold it up and put it in your head—is capable of understanding calculus and making up jaunty little tunes and comparing Kierkegaard to Heidegger, not to mention doing all three in a single afternoon.

It’s hard to believe that the wide world of human thought can come from such a comparatively small albeit complicated structure, and my guess is that it doesn’t. It’s not that I believe in a soul or immaterial mind or anything like that, but I think that probably there is a lot less going on in our thinking than we think there is. Our thinking and our experience is extremely gappy, and we spackle over the gaps with a paste of fictions, supplied mainly through language and culture. Read more »

by Deanna Kreisel (Doctor Waffle Blog)

I assume that if your eye was drawn to this essay, then you are also troubled by feelings of rage. But I don’t want to be presumptuous—there are other reasons to read an essay that promises to tell you what to do with your anger. Maybe you think I have an agenda. Perhaps you have formed an idea of what my rage is about, and you disagree with that figment, and you are hate-reading these words right now, waiting for me to reveal the source of my own rage so that you can write a nasty comment at the end of this post or troll me on social media or try to cancel me or dox me or incite violence against me or come to my house and sneak onto my porch and stare balefully into my front windows or throw an egg at my car or trample deliberately on the ox-eye sunflowers that are bursting around my mailbox or put a bomb in my mailbox or disagree with me strenuously in your heart. There is a wide range of potential negative responses, and I don’t have time to list them all. The point here is that one must contend with them, and that is another reason to feel rage.

I assume that if your eye was drawn to this essay, then you are also troubled by feelings of rage. But I don’t want to be presumptuous—there are other reasons to read an essay that promises to tell you what to do with your anger. Maybe you think I have an agenda. Perhaps you have formed an idea of what my rage is about, and you disagree with that figment, and you are hate-reading these words right now, waiting for me to reveal the source of my own rage so that you can write a nasty comment at the end of this post or troll me on social media or try to cancel me or dox me or incite violence against me or come to my house and sneak onto my porch and stare balefully into my front windows or throw an egg at my car or trample deliberately on the ox-eye sunflowers that are bursting around my mailbox or put a bomb in my mailbox or disagree with me strenuously in your heart. There is a wide range of potential negative responses, and I don’t have time to list them all. The point here is that one must contend with them, and that is another reason to feel rage.

But to return to my opening supposition: all of these possible responses are also born of rage, so I imagine that you might benefit from an essay about what to do with your rage even if your rage is rage at my rage.

So let’s begin. Read more »

by Mary Hrovat

When the city of Melbourne set up email addresses for trees so that people could report problems, the trees received affectionate fan mail as well as messages about dangling limbs or other hazards. Here are some letters I’d write to trees, if I could.

To the aspens in Hannagan Meadow

I saw you in fall 1979; I’d been married to my first husband for only a few months. We traveled a lot that fall, scouting out places we might like to live out our back-to-the-land dreams and raise a family.

I was only 18, and I’d never lived in the country. I wasn’t sure I was ready for life with cows and chickens and a big garden. Sometimes, especially when we were driving at night through what seemed like the lonelier corners of Arizona, I was frightened at what I’d gotten myself into. Maybe my husband and I both were, but we couldn’t tell each other.

When I saw you, we were halfway up the Coronado Trail Scenic Byway from Clifton to Springerville, in eastern Arizona. This highway covers only 129 miles, but it’s a slow, dramatic drive, up and down through the White Mountains along curves and switchbacks.

We stopped at Hannagan Meadow for a break. You were probably the first stand of aspens I’d seen in fall colors, tall and slender with yellow leaves against beautiful white bark. I loved your brilliance and the movement of your glowing leaves against a more somber backdrop of tall evergreens. I didn’t know much about aspens, but I wonder now if all of you, the aspens I saw that day, are part of a single clonal community.

The sight of you in that meadow, tall and bright in the sunshine, dazzled and comforted me. You called me out of myself and my worries. Among all the beautiful things I saw that fall, you’re the one that has remained most vivid in my memory. I hope you’re still there. I’d like to see you again someday. Read more »

by David Greer

And I shall have some peace there, for peace comes dropping slow,

Dropping from the veils of the morning to where the cricket sings;

There midnight’s all a glimmer, and noon a purple glow,

And evening full of the linnet’s wings.

—Excerpt from The Lake Isle of Innisfree, by William Butler Yeats

Our people lived as part of everything. We were so much a part of nature, we were just like the birds, the animals, the fish. We were like the mountains. Our people lived that way. We knew there was an intelligence, a strength, a power, far beyond ourselves…. Everybody had the right to comfort, to security, the right to food, a home, the use of the land. This is because we believed that everything was put here by a great and wonderful intelligence.

—Excerpt from Saltwater People, by Dave Elliott

Visitors to my cabin in a forest glade on a small island in the Salish Sea almost always remark upon the silence. It’s true, if you’re freshly arrived from an urban community, the silence at first seems absolute and a little overwhelming. It’s only when you quiet yourself that the silence surrounding you starts to come alive with the texture and colour of natural sounds.

Some sounds may seem easily identifiable to visitors if only because their creators are visible. The slow thunk-thunk-thunk of a raven’s wings beating the air as it passes arrow-straight across the circle of blue sky over the glade. The chittering of a bald eagle high in a fir. The cat-like mew of a red-eyed spotted towhee rooting through underbrush. Other noises require more careful observation and familiarity but are instantly identifiable to those who know them. The faint scrape of the jaws of a yellowjacket backing down a cedar post, a grey ball of nest paper slowly enlarging beneath its mandibles. The lazy kre-e-e-eck? deep in a cedar, like a creaking rusty door in a haunted house: the territorial call of a male Pacific tree frog, gold and green and shadow-secluded. The urgent whistling of a juvenile barred owl, harassing its parent for freshly killed flesh. And in the gloaming, not the soft sound of the linnet’s wings, but those of its close cousin the house finch in this part of the world six thousand miles from Yeats country. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Fabio Tollon

I take it as relatively uncontroversial that you, dear reader, experience emotions. There are times when you feel sad, happy, relieved, overjoyed, pessimistic, or hopeful. Often it is difficult to know exactly which emotion we are feeling at a particular point in time, but, for the most part, we can be fairly confident that we are experiencing some kind of emotion. Now we might ask, how do you know that others are experiencing emotions? While, straightforwardly enough, they could tell you. But, more often than not, we read into their body language, tone, and overall behaviour in order to figure out what might be going on inside their heads. Now, we might ask, what is stopping a machine from doing all of these things? Can a robot have emotions? I’m not really convinced that this question makes sense, given the kinds of things that robots are. However, I have the sense whether or not robots can really have emotions is independent of whether we will treat as if they have emotions. So, the metaphysics seems to be a bit messy, so I’m going to do something naughty and bracket the metaphysics. Let’s take the as if seriously, and consider social robots.

Taking this pragmatic approach means we don’t need to have a refined theory of what emotions are, or whether agents “really” have them or not. Instead, we can ask questions about how likely it is that humans will attribute emotions or agency to robots. Turns out, we do this all the time! Human beings seem to have a natural propensity to attribute consciousness and agency (phenomena that are often closely linked to the ability to have emotions) to entities that look and behave as if they have those properties. This kind of tendency seems to be a product of our pattern tracking abilities: if things behave in a certain way, we put them in a certain category, and this helps us keep track of and make sense of the world around us.

While this kind of strategy makes little sense if we are trying to explain and understand the inner workings of a system, it makes a great deal of sense if all we are interested in is trying to predict how an entity might behave or respond. Consider the famous case of bomb-defusing robots, which are modelled on stick insects. Read more »

by Mindy Clegg

From the start, punk rock was a translocal phenomenon. Punks in London took influence from their New York City counterparts. The British Invasion of punk inspired a new generation of young North Americans to blast out three chords and embrace DIY. By the early 1980s, punk scenes existed across the western world, into the global south, the Eastern Bloc, and non-aligned world. Many of these scenes went underground as part of the hardcore wave of punk rock. But other punk genres emerged that challenged dominant nationalist or imperial narratives with a bottom-up perspective. Post-colonial punks included artists that sought to employ a punk rock attitude to champion previously colonized and marginalized cultures.

The debate over whether punk is political began with the birth of the subculture. Many of the first wave punk bands are generally understood as non-political. But these “non-political” bands sometimes made political statements. The Ramones mocked President Reagan with “Bonzo Goes to Bitburg.”

by Rafiq Kathwari

When I ask, how does it rain?

You rap a bead of sweat on your forehead.

When I ask, how does lighting strike?

You glance at me and lower your eyes.

When I ask, how does day meet night?

You veil your face with hair.

When I ask, where does music get its magic?

You spike your talk with honey.

When I ask, what good is yearning?

You snuff a candle with your robe’s hem.

For Annie Zaidi

by Brooks Riley

Every beloved object is the center point of a paradise. —Novalis

The first full moon I saw after the procedure looked as if it might burst, like a balloon with too much helium. It was just above the horizon, fat and dark yellow —moving slowly upward to the firmament where it would later appear smaller and take on a whiter shade of pale. I could distinguish its tranquil seas, the old familiar terrain coinciding with a long abandoned memory.

The first full moon I saw after the procedure looked as if it might burst, like a balloon with too much helium. It was just above the horizon, fat and dark yellow —moving slowly upward to the firmament where it would later appear smaller and take on a whiter shade of pale. I could distinguish its tranquil seas, the old familiar terrain coinciding with a long abandoned memory.

It had been a while since I’d seen the full moon this way. For far too many moons, all I had seen were the fractured doubled contours of an indeterminate object in the night sky where the moon should have been. The problem was cataracts, or clouding of the ocular lens.

Advancing age metes out decline in increments. I hardly noticed the changes in my vision. Spending so much time on the internet, I was getting second-hand access to the world and its visual splendor and diversity through photographs and videos—none of which prepared me for the increasing inexactness that met my gaze wherever I went.

***

Even before the bandage came off, the implant’s ID card seemed to confirm it: I am a camera—with a new Zeiss lens made in Jena. Jena is back in my life.

Even before the bandage came off, the implant’s ID card seemed to confirm it: I am a camera—with a new Zeiss lens made in Jena. Jena is back in my life.

How can that be, when I’ve never visited the city, only passed through its train station on my way to nearby Weimar? As I cautiously open my left eye to a rush of fine details I couldn’t see a week ago, the first words that come to mind are Jena Paradies, the name of the train stop that always made me smile. Jena’s Paradise is a nearby park. Mine is a second chance at sight. Read more »

by Mark Harvey

On the morning of July 22, 2016, an illegal campfire in Garrapata State Park near Carmel, California got out of control. Within a day, the fire grew to 2,000 acres. Within two days the fire grew to 10,000 acres. A month later the fire was at 90,000 acres and still largely uncontained. Ultimately the Forest Service and other agencies deployed thousands of firefighters and spent close to $260 million in an effort to contain it. The fire was finally “contained” three months later in October. During the three months of the fire’s life, bulldozers cut close to 60 miles of roads/firebreaks and aerial tankers dumped about 3.5 million gallons of fire retardant on the flames. The bulldozing and the aerial retardant work had little effect and what really helped put the fire out was October’s cooler temperatures and more humid air.

The fact of the matter is most wildfires go out by themselves.

The effort to fight large wildfires with expensive planes, helicopters, fire retardant, and bulldozers has been likened to fighting hurricanes or earthquakes: it’s costly and mostly futile. While developing fire-resistant lines and fireproofing buildings at the urban-forest interface can be very effective, trying to control massive blazes of tens of thousands of acres is like burning money.

Fighting wildfires is big business. When you stage thousands of firefighters in camps, you need catering services, laundry services, mobile housing, heavy equipment, and fuel. Caterers can gross millions of dollars to support large crews and local landowners make thousands of dollars renting their land and facilities for staging areas. Read more »