by Godfrey Onime

I am reminded of an observation made by an African comedian at a wedding reception I once attended in Atlanta. He quipped that the English language tends to identify even the most hideous diseases by the most beautiful names. Names so lyrical, so poetic, so sensuous you almost wish to contract the disease. He rattled off some examples: Hepatitis. Cholecystitis. Syphilis. Cancer. “How beautiful!” he exclaimed.

The jokester contrasted this proclivity with some gruesome names Africans assign to even the most benign conditions, such as with the Yorubas of Nigeria — Lapalapa (for dermatitis); or jedijedi (for diarrhea). The comedian may romanticize the English names for diseases, but not so with most of my patients. Especially not so with the middle-aged woman whom I diagnosed with syphilis a few years back. “You mean my nose could fall off?” seemed to be her biggest fear, explaining that she once heard that syphilis could destroy the “snout,” as she put it.

I scrutinized the woman, taking in her straight nose and high cheekbones. Giggling, I said, “Maybe you get to go back in time and join the ‘No Nose Club’. Perhaps you could find out who Mr. Crumpton really was.”

“Mr. who?”

###

Beautiful or not, it turns out that the origin of the name for syphilis, ironically, came from a poem, written by Girolamo Fracastoro, an Italian physician, scholar and poet. The poem, Syphilis sive morbus gallicus (translated to Syphilis or The French Disease), tells the story of a shepherd boy named Syphilis who angered the Greek god Apollo and was given the disease bearing his name as punishment. Although the affliction was more colloquially called “The Pox,” the term syphilis stuck as the proper name.

What perhaps is most fascinating about this disease is how throughout history its story keeps shifting — from its origins to how society dealt with its aftermath. Lacking effective treatment until this past century, the effects of the infection was not only quite disfiguring and often repulsive, but the disease was stigmatized. By the early 1500s, when German physician and humanist Joseph Grunpeck contracted the ailment, he described it as “so cruel, so distressing, so appalling that until now nothing more terrible or disgusting has ever been known on this earth.”

Little wonder, then, that although syphilis was first described in Europe in the 1490s, no country wished to claim ownership of its origin. There was endless finger-pointing everywhere, an epic xenophobic-blame-the-foreigner. The English called it “The French Disease.” The French called it “The Italian Disease.” The Italians dubbed it “The Turkish Disease.” To the Russians, it was “The Polish Disease,” while the Japanese settled for “The Portuguese Disease.” In Northern India, the Muslims believed it was the Hindu’s fault. And to the Hindu, well… the Muslims were to blame. Over time though, its origin has been chucked up to the “New-world” — the indigenous Americans. The legend is that, since the disease was unknown in Europe before Christopher Columbus returned from the Americas, his men must have romanced the bug there and it hitched a ride back home with them. New findings, however, continue to challenge this theory of its origins in the Americas.

When untreated, as was the case for much of history when it was incurable, a syphilitic infections can seem to disappear after an initial, usually painless sore on the genitalia, only to return months and then years later with untold complications to the internal organs, such as cardiac and neurological complications. In addition, it often caused gruesome external disfigurement, including to the skin, forehead, as well as deformity and eradication of the nose — hence my patient’s fixation on her “snout.” Many of these changes can also be associated with intense pain.

In the poem where he named syphilis, Fracastoro blamed the disease on a corruption of the air, which was common in classical medicine as the origin of diseases. Later, however, in a second more medical work, he described the contagion as passed from an infected person through direct contact. We now know that syphilis is transmitted through sexual intercourse and that the disease is caused by a cork-screw bacteria called Treponema pallidum, or simply, T. pallidum.

In the third (tertiary) stage of a syphilitic infection, medical symptoms can be severe. It affects the bones, heart, and blood vessels, and can trigger stroke. The brain and nervous system are also commonly affected, causing conditions such as dementia, blindness, or paralysis. Many of these findings were learned from the now infamous Tuskegee experiments in the United States, where doctors followed black men in Alabama for as long as forty years without treatment, even though a cure had become available.

In the pre-plastic surgery era, the disfigurement to the nose caused by syphilis fueled much of the associated stigmatization. This is not hard to imagine. Noelle Gallagher, an expert in Eighteenth-Century Literature and Culture at the University of Manchester, and author of Itch, Clap and Pox, has argued about the singular importance of the nose in popular culture. Of the myriad symptoms of “the pox,” she postulated—a list that could include genital sores or chancres, swellings of the lymph glands, severe skin rashes, spinal deformity, dementia, and bone pain—none was more undeniable, more exposed to public scrutiny and condemnation, than the collapsed nose. The persons afflicted with this particular complication were seen as harbingers of death, and in cultures like the class-conscious Europe, they were further considered social and genetic outcasts.

Consider that long before the syphilis epidemic, the nose was a measure of superiority, what with the abundance of such phrases in popular language as “looking down one’s nose,” “holding one’s nose in the air,” and “turning one’s nose up”—all employing the nose as a symbol of class-based discrimination, according to Gallagher. Christians had equally for centuries distinguished their “straight” noses from the allegedly “hooked” noses of Jews; even the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Anglicans ridiculed the Protestant dissenters in part as intoning hymns and prayers “through the nose.”

But the shape and size of one’s nose went further than social status; it was a measure of the degree of personhood itself. When they began to develop theories about race, eighteenth-century Naturalists like Oliver Goldsmith and Georges-Louis Leclerc theorized that the “flat” African nose was a marker of biological inferiority, explained Gallagher. Further, early scientists attempting to distinguish between mankind and his nearest relative in the animal kingdom seized upon the nose: the flatter the nose, the lower in the animal kingdom. Hence, according to the eighteenth-century French physician Jean Astruc, the nasal destruction caused by venereal disease could render a man “flat-fac’d like an ape.”

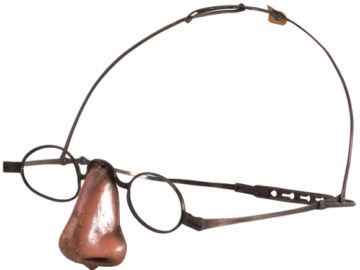

Little wonder then that many whose noses were destroyed by syphilis tried to hide the deformities through various contraptions, such as one that the Royal College of physicians made for a Victorian London woman — a prosthetic nose held in place on a pair of glasses. The woman had contracted syphilis from her husband and subsequently lost her nose.

Contraptions or not (which for one were very expensive), it was obvious that persons with no noses were banished to a life not only of shame and social isolation, but of self-repulsion. Then, entered Mr. Crumpton, whom I had mentioned to my patient, although it is believed that was not his real name.

Himself a distinguished nobility who was not noseless, by the year 1709 he set out on the streets of London in search of the less fortunate — those without noses. When he met such persons, he invited them to the Covent-Garden Tavern at a certain time where he promised to share a secret with them.

On the appointed day and time, Mr. Crumpton put on a feast at the tavern and warned the staff not to be too surprised about the appearances of his guests. When one by one the guests began to arrive, they were ushered upstairs to their private dining area. At this point, none of the attendees knew what secrets they were there to learn. At first, Mr. Crumpton was nowhere to be found, but he soon materialized. His guests were pleasantly surprised when he shared the secret: that he intended for them to join a group of people who looked just like them. As one attendee reported to the newspaper, The Star,

“As the number increased, the surprise grew the greater among all that were present, who stared at one another with unaccustomed bashfulness and confused oddness, as if every sinner beheld his own iniquities in the faces of his companions”.

Thus the ‘No Nose Club’ was born. After dinner, the merriment continued with drinks and wisecracks. For once in their lives, it was “as if their Sins were their Pride & their Sufferings their glory.”

Today we are used to group meetings, from persons with AIDS to those who suffer from various addictions, breast cancer, or even persons with psoriasis. But this medical gathering of the No Nose Club is believed to be one of the earliest of persons with similar afflictions. Here they were, coming from the unforgiving world outside, to meet and laugh and mingle — and perhaps fall in love — with those who accepted them for who they were.

After that first auspicious meeting, the newspaper report went on to say,

“This club met every month for a whole joyous year, when its founder died, and the flat-faced community was unhappily dissolved.“ Their last meeting was at Mr. Crumpton’s funeral, where an elegy for him read:

“Mourn for the loss of such a generous friend,

Whose lofty Nose no humble snout disdain’d;

But tho’ of Roman height, could stoop so low

As to soothe those who ne’er a Nose could show.

Ah! sure no noseless club could ever find

One single Nose so bountiful and kind.

But now, alas! he’s sunk into the deep,

Where neither kings or slaves a Nose shall keep”…

After telling my patient the story of the No Nose Club, I assured her that she was not likely to lose her nose, as Penicillin, an effective treatment for her affliction, was now available.

“You mean I may not have to wear a prosthetic nose like the woman who got syphilis from her scumbag husband?” she asked in jest.

“No,” I said.

And it turned out that the Victorian London woman did not have to wear her contraption for too long either. According to historian Lindsay Fitzharris and author of The Butchering Art, her husband had died, presumably of syphilis, and she again found love. On remarrying, she returned the prosthesis to her doctor. When asked why, she stated that her new husband liked her just the way she was, flat-faced and all, so that she did not need the gadget anymore.

###

I’ll like to revisit the quipping of the African comedian at the wedding reception I attended in Atlanta a few years back. As I remember it, marriage, he had also proposed, is tough no matter how much in love the couple may seem at first. When the going gets tough, the couple must learn from the West and believe their troubles are not insurmountable. “Pretend your diseases are not hideous,” he had advised. “Instead of calling your rash lapalapa, pretend it is the most beautiful thing on earth. Call it by its English name — it’s glorious, sensuous, lyrical, poetic name. Call it psoriasis.”

Mr. Crumpton very well understood that, too.