by Andrea Scrima

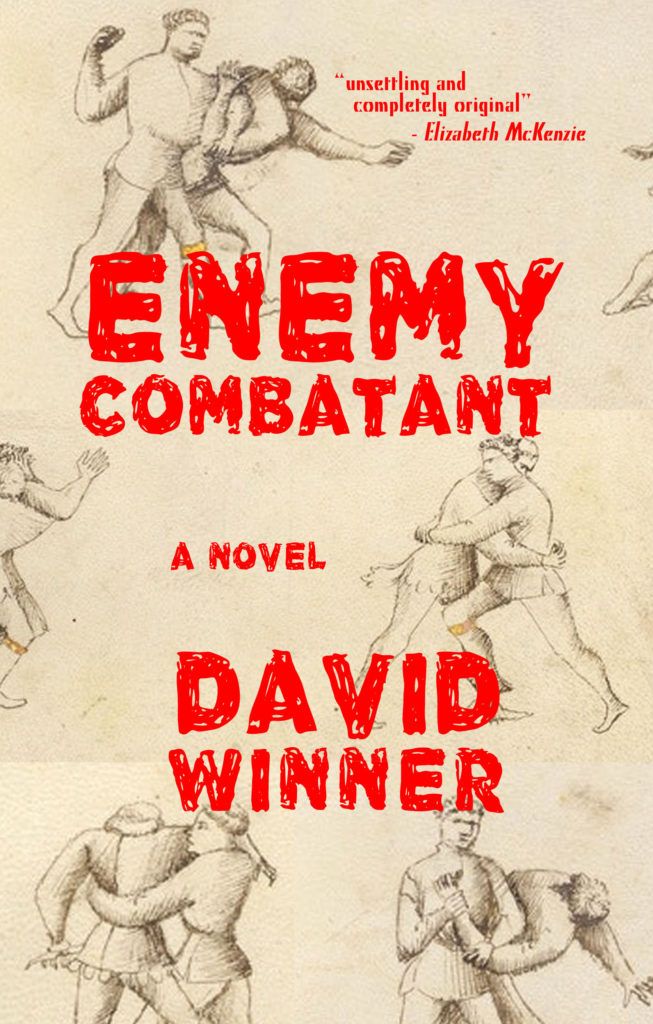

David Winner’s third novel, Enemy Combatant, has just been published by Outpost19 Books and has already received a starred Kirkus review. The book is an action-packed road trip gone horribly haywire, a misadventure mired in alcoholic debauchery and doomscrolling-induced moral indignation at the imperial arrogance of the Bush administration following 9/11. Sensitively and intelligently written, it wobbles between the tragic, comic, and utterly ridiculous as two close friends set out to free someone, anyone, from one of the extra-judicial black-op sites the US set up in the Caucasus and elsewhere and document the evidence. I spoke to David about some of the ideas behind his tragicomic page-turner.

Andrea Scrima: Your new novel, Enemy Combatant, looks back to the Bush era from a point in time still buckling under the enormous pressure of the Trump administration. Before the book even gets underway, we’re given a comparison between these two periods in recent American history: the stolen election of 2000, September 11 and the wars that followed, the reintroduction of enhanced interrogation and torture and, of course, the black-op sites you home in on in your novel—as opposed to kids in cages, half a million Covid deaths, withdrawing from the Paris Treaty and everything else the past administration was infamous for. Looking back over the past 20 years, what similarities do you see between these two periods, and what are the key differences?

David Winner: I don’t like using “neo-liberal” because it’s such a bogeyman term, but it comes in handy while describing the Bush years. There was a hawkish consensus in the United States, a thirst for blood, stemming from 9/11. It’s hard to separate Bush from both Clintons and Tony Blair as they, along with the “reliably liberal” New York Times and The New Yorker, all supported the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan, which turned out to be a slippery slope to torture. Like the protagonist of Enemy Combatant, I was infuriated by the Bush administration, a fury that was aggravated by the sense of being part of a small minority whose conventional left-wing belief in the flawed history of American foreign policy didn’t get flipped around when the towers came down. Read more »