by Thomas O’Dwyer

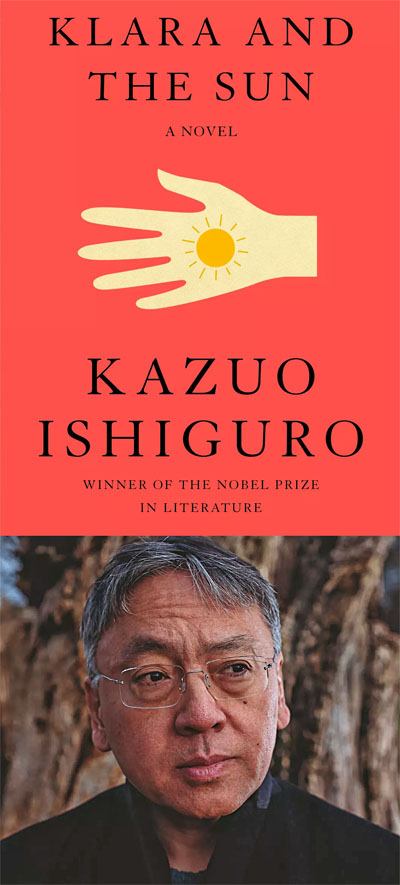

For some time, Sir Kazuo Ishiguro has been slyly replacing Dame Iris Murdoch as the author to whom I most regularly return. His enchanting and disturbing new novel, Klara and the Sun, his first since winning the 2017 Nobel Prize, is unlikely to diminish this trend. I wrote in a previous column: “Iris was my ‘first’ at age 15 – first adult novelist and first woman writer, and she has remained fixed in my affections over the decades. Under the Net was also her first novel, published in 1954.” Time has moved on from Murdoch’s vanishing fictional worlds, from their now decrepit or deceased characters and their dated opinions. In recent decades we have been hovering on the fuzzy frontier of a strange near-future which many of us will not live to see clearly. Ishiguro seems to have a glimpse of it, and his vision leaves his readers both curious and queasy. Iris Murdoch can lead us, like Lawrence Durrell’s Justine, “link by link along the iron chains of memory to the city which we inhabited so briefly together.” It’s a firm and familiar journey, remembering the foreign country of the past. Ishiguro is eerier — he seems to be forcing us to remember the future. It hasn’t arrived yet, but it already feels as familiar and uncomfortable as our own past mistakes.

For some time, Sir Kazuo Ishiguro has been slyly replacing Dame Iris Murdoch as the author to whom I most regularly return. His enchanting and disturbing new novel, Klara and the Sun, his first since winning the 2017 Nobel Prize, is unlikely to diminish this trend. I wrote in a previous column: “Iris was my ‘first’ at age 15 – first adult novelist and first woman writer, and she has remained fixed in my affections over the decades. Under the Net was also her first novel, published in 1954.” Time has moved on from Murdoch’s vanishing fictional worlds, from their now decrepit or deceased characters and their dated opinions. In recent decades we have been hovering on the fuzzy frontier of a strange near-future which many of us will not live to see clearly. Ishiguro seems to have a glimpse of it, and his vision leaves his readers both curious and queasy. Iris Murdoch can lead us, like Lawrence Durrell’s Justine, “link by link along the iron chains of memory to the city which we inhabited so briefly together.” It’s a firm and familiar journey, remembering the foreign country of the past. Ishiguro is eerier — he seems to be forcing us to remember the future. It hasn’t arrived yet, but it already feels as familiar and uncomfortable as our own past mistakes.

Ishiguro’s first novel was A Pale View of Hills, but the first I read was An Artist of the Floating World. Both dealt with post-war Japan, so, given his name and topics, I lazily assumed this was a new Japanese writer in translation. Was he perhaps someone who would transcend his native language and become an international star like Colombia’s Gabriel García Márquez or Portugal’s José Saramago? Of course, he was not. He’s more like an Iris Murdoch, a rare specimen of a quintessentially English writer who arrived in England from somewhere else and, like her, became British enough to be knighted by the Queen. Ishiguro was born in Nagasaki. When he was five, his scientist father accepted a research post in England at the National Institute of Oceanography. The family settled permanently at Guildford in Surrey. Ishiguro had a complete British education, from grammar school to Kent University and a creative writing master’s degree at East Anglia University. He published A Pale View of Hills in 1982, aged 28.

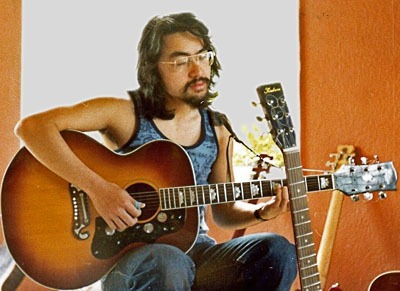

“If you’d come across me in the autumn of 1979, you might have had some difficulty placing me, socially or even racially,” Ishiguro said in his Nobel acceptance address in Stockholm. “I was 24 years old; my features would have looked Japanese, but … I had hair down to my shoulders and a drooping bandit-style moustache. The only accent discernible in my speech was that of someone brought up in the southern counties of England, inflected at times by the languid, already dated vernacular of the Hippie era.” He was frequently photographed in black leather, playing the guitar and was a serious fan of Bob Dylan (who won the Literature Nobel one year before Ishiguro). However, he also said in an interview with Reuters at the time: “Although I’ve grown up in England and I’m educated in this country, a large part of my way of looking at the world, my artistic approach, is Japanese, because I was brought up by Japanese parents, speaking in Japanese. I have always looked at the world through my parents’ eyes.”

Ishiguro set his first two novels after World War II when significant changes were taking place in Japan. If the author’s “westernisation” in England was smooth, natural and complete, it was something else in Japanese society. The culture of his parents meshed seamlessly with the assimilated English culture of Ishiguro, but in Japan, the advance of Western views under the American occupation created huge rifts between the past and the proposed future, as represented in the old and young generations. Ishiguro had not yet visited Japan when these novels were published, so his post-war Japan is an imagined place and second-hand. (He set Pale Hills in England, but the characters and themes address Japanese people in a changing world. Floating World is his only novel set in Japan). The books cover aspects of culture usually associated with stereotypical Japan — local food, tea ceremonies, politeness, arranged marriages. Stereotypes are not necessarily wrong, but they are always incomplete, and Ishiguro fleshes out stereotypical Japanese into real people. (There is, however, room for discussion on whether Ishiguro makes any attempt to break with Japanese stereotypes about Western and other foreign characters.)

The Artist of the Floating World is a masterpiece placed in the hands of an unreliable narrator, Masuji Ono. Now a garrulous old man, Ono had been a respected artist and nationalist propagandist in the 1930s and during the war. Without admitting it to himself, he is crafting a revisionist version of his entire life. Everything has become problematic — his art legacy, his modernising family, the contempt of youth for their war-mongering parents. The new generation blames him for his part in the belligerent policies, and he has to confront the realities of modern times — his grandson, the salaryman culture, women demanding rights and opportunities. Ishiguro’s artistic style elements fall deftly into place, the threads from which he has woven all his subsequent novels. There is menace, uneasy calm, memories from old landscapes straining to re-invent a painter’s wasted life that once had been a success.

After two Japan-themed novels, critics and readers assumed this was the permanent air on which Ishiguro would play new variations, exploring his parents’ beloved Japanese culture in his bright modern English. The critics were proved wrong, but also right, a typically Ishigurian conundrum, when in 1989 The Remains of the Day startled and delighted the international world of books. The unreliable construct of delusional memory was still there, but Japan was gone, and with uncanny expertise, Ishiguro placed his characters in the ultimate English cliché — a traditional aristocratic country manor. The novel secured Ishiguro an immediate Booker Prize and probably his future Nobel. At that later award ceremony, the President of the Swedish Academy eulogised The Remains of the Day, which he compared to a mix of Jane Austen and Franz Kafka:

“Before we know it, we are sliding down into the abyss of existence. The novel concludes in tragedy – a tragedy of missed opportunities. As a bonus, one gets the sociology of an older class society. Yet the perspective includes a redemptive aspect – not, to be sure, concerning the social order, but certainly the people in it. Ishiguro’s world is a world without heroes. And equally important: there are no predators insight – and consequently no victims.”

The Remains of the Day movie, starring Anthony Hopkins and Emma Thompson, propelled Ishiguro to international fame beyond the world of book-readers. Despite the entirely different settings, the book is a mirror image of The Artist of the Floating World, though it’s a more polished and less ambiguous story. It may seem an easier read for Westerners, if only because the English country house and its upstairs-downstairs characters make it more familiar. Nonetheless, it shares the same lost-world themes, unreliable protagonist and lives made pointless by memory as did Ono’s floating world. The novel still vies for first place in reader surveys with Ishiguro’s undisputed later masterpiece, Never Let Me Go.

Between these two novels, Ishiguro published two reasonably unsuccessful volumes, The Unconsoled and When We Were Orphans, in which he attempted to explore new directions. When We Were Orphans, set in wartime Shanghai, follows a British detective trying to solve a mysterious case. The Unconsoled, his longest and most challenging book, has attracted that most meaningless literary adjective “Kafkaesque.” That was enough for me at least to put it on my “maybe sometime” reading list. The Orphans detective story also raised some questions about Ishiguro’s perceived drift into so-called genre fiction, reinforced by the futuristic theme of Never Let Me Go and now Klara and the Sun. Such tut-tutting could once be the kiss of death for a literary writer in the self-policing world of English academia. In the real world of literature lovers, this is nonsense, of course. Ishiguro is no sci-fi hack but a literary artist of the future world.

Between Never Let Me Go and Klara and the Sun, we got another strange Ishiguro tale, The Buried Giant. It’s set in an alternative and foggy medieval world of Arthurian legend in which (surprise, surprise) no-one can retain any long term memories. An elderly couple dimly remembers that they might once have had a son and travel to another village to try to find him. The book was nominated for a 2016 World Fantasy Award for best novel, and one could almost hear the sniffs of disapproval from academia’s fossilising copses. The Nobel may have arrived just in time to keep Ishiguro on faculty Eng. Lit. shelves.

And so to March 2021 and Klara and the Sun. For the first time, I opted to download an Ishiguro from Audible to hear his unreliable narrator speak for herself. It’s a fine reading experience, but I’m starting to fear it might be in my head forever. A naive and delightful Siri with brains, infinitely inquisitive, will forever ask: “Thomas, could you please explain to me why …” Why we humans behave as we do, why we are cruel for no reason, why we abuse our children to satisfy our egos, why we cannot love without causing pain. Why can’t we control our technology and make sure it does not harm our nearest and dearest. And why, as we advance, do we retain a vicious class and wealth system that allows so few to benefit from scientific breakthroughs in health and genetics – including the enhancement central to Klara and the Sun – while so many are denied access.

This column does not aim to be a review, because so few of you will yet have read it, and it’s a tough book to describe without dropping spoilers. Klara is forever questioning, observing and exploring, and Ishiguro cunningly requires the reader to uncover what she is seeking along with her, with surprising snippets of revelation along the way. Ishiguro spoke to Irish RTE radio when Klara was published this month:

“I’ve always liked narrators who have very limited vision. And in a way, we readers can see what she’s not seeing. And it also allows me to focus very much on very specific things. So Klara, because she’s a machine that’s been created to stop teenagers from becoming lonely, certainly initially, she sees everything through the lens of loneliness.”

You may already be getting a hint of that infinitely sad nausea from Never Let Me Go, and you’re not wrong, but this is a very different novel, less horrifying but more poignant in different ways. Futuristic stories tend towards Black Mirror dystopia, but Ishiguro is surprisingly (though not exceedingly) optimistic about artificial intelligence and gene editing. Klara is an AF – or artificial friend – whom we first meet as she waits in a store window for a human child to persuade a wealthy parent to buy her. Klara is so enthralled by the Sun, her “source of nourishment” as she calls the solar energy that drives her, that our mundane star itself becomes a character. She keenly observes and tries to interpret the humans passing by on the street. Klara has developing feelings but incomplete knowledge and has never been “outside.” She tries to calculate how many of the passersby are lonely. Klara’s understanding begins to expand as a girl, Josie, chooses her, and she becomes curious about aspects of humanity beyond loneliness.

What do human beings mean when they say they love each other? When members of a family struggle with these emotions? And she asks if there is something unique about each individual that makes them special and not replaceable? Artificial Klara is more human than most humans, and she is an Ishiguro gem that gleams. Klara means brightness, and she worships the Sun, her source of power, with naive spiritual delight. From her store window, Klara observes a man in a ragged raincoat on the far side of the street, waving and calling to an old woman on the near side. The “coffee-cup-shaped” woman freezes in place, then crosses hesitantly to him, and they cling to each other. Klara notices “raincoat man’s” tightly shut eyes as he hugs the woman. “They seem so happy,” she says to Manager, the store supervisor. “But it’s strange because they also seem upset.”

“Oh, Klara,” Manager says. “You never miss a thing, do you? Perhaps they hadn’t met for a long time. A long, long time. Perhaps when they last held each other like that, they were still young.”

“Do you mean, Manager, that they lost each other?”

“Yes,” she said, “that must be it. They lost each other. And perhaps just now, just by chance, they found each other again. Sometimes, at special moments like that, people feel pain alongside their happiness. I’m glad you observe everything so carefully, Klara.” She considers it her duty to empathise. If she doesn’t, she thinks, “I’d never be able to help my child as well as I should.”

Klara and the Sun looks at our changing world through the eyes of an unforgettable narrator, exploring the most fundamental human question — what does it mean to love? It’s a profoundly satisfying book written in a language so simple it seems childlike (though never childish). But it still leaves Isishiguro’s mastery of the written word on full display. In its award citation, the Nobel committee described Ishiguro’s books as “novels of great emotional force”, and it said he has “uncovered the abyss beneath our illusory sense of connection with the world.” If the ground shifts slightly beneath your feet as you read this novel, you’ll recognise what the voice of Klara evokes. It’s what we’ve all been feeling for the last year.