by Jochen Szangolies

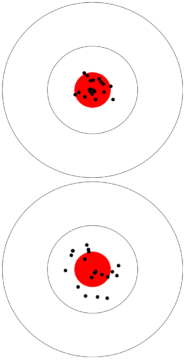

The world is a noisy place. No, I don’t mean the racket the neighbor’s kids are making in the back yard. Rather, I mean that, whatever you encounter in the world, probably isn’t exactly what’s actually there.

Let me explain. Suppose you’re fixing yourself a nice cocktail to enjoy on the porch in the sun (if those kids ever quiet down, that is). The recipe calls for 50 ml of vodka. You’re probably not going to measure out the exact amount drop by drop with a volumetric pipette; rather, maybe you use a measuring cup, or if you’ve got some experience (or this isn’t your first), you might just eyeball it.

But this will introduce unavoidable variations: you might pour a dash too much, or too little. Each such variation means that this particular Moscow Mule differs from the one before, and the one after—each is a slight variation on the ‘Moscow Mule’-theme. Recognizably the same, yet slightly different.

This difference is what is meant by ‘noise’: statistical variations in the measured value of a quantity due to inescapable limits to precision. For most everyday cases, noise matters comparatively little; but if you overshoot too much, your Mule might pack more kick than intended, and either just taste worse, or even make you yell at those pesky kids for harshing your mellow.

Thus, noise can have real-world consequences. Moreover, virtually everything is noisy: not just simple estimations of measurable quantities, like volumes, sizes, or time spans, but also less easily quantifiable items, like decisions or judgments. The latter is the topic of Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment, the new book by economy Nobel laureate Daniel Kahnemann, together with legal scholar Cass Sunstein and strategy expert Olivier Sibony. The book contains many striking examples of how noisy judgment leads to wide variance in fields like criminal sentencing, college admissions, or job recruitment. Thus, whether you get the job or go to jail might come down to little more than random variation, in extreme cases.

But noise has another effect that, I want to argue, can shed some light on why so many people seem to hold weird beliefs: it can make the correct explanation seem ill-suited to the evidence, and thus, favor an incorrect one that appears to fit better. Let’s look at a simple example. Read more »

Going back and reading one’s favorite authors is like seeing an old friend after a long absence: things fall into place, you remember why it is you get along with and like the other person, and their idiosyncrasies and unique character reappear and interact with your own, making old patterns reemerge and lighting up parts of you that have long been dormant.

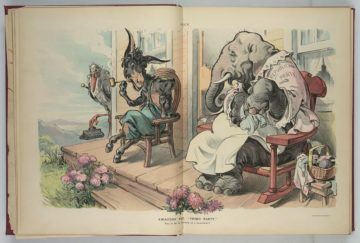

Going back and reading one’s favorite authors is like seeing an old friend after a long absence: things fall into place, you remember why it is you get along with and like the other person, and their idiosyncrasies and unique character reappear and interact with your own, making old patterns reemerge and lighting up parts of you that have long been dormant. The western admirers of Amartya Sen as a public intellectual may not be aware that he is actually in a long line of globally engaged cultural elite that Bengal has produced. (This is true to some extent of the elite elsewhere in India as well, particularly around Chennai and Mumbai, but I think in sheer scale over the last two hundred years, Bengal may have a special claim). One aspect of this phenomenon is worth reflecting on. These members of the cultural elite were well-versed in the manifold offerings of the West, but they came to them with a solid grounding in the cultural wealth of India. Take Ram Mohan Roy (1772-1833). He was, as Nehru describes him in his Discovery of India, “deeply versed in Indian thought and philosophy, a scholar of Sanskrit, Persian and Arabic, ..a product of the mixed Hindu-Muslim culture, …the world’s first scholar of the science of Comparative Religion.” He contributed to the development of Bengali prose. He was a social reformer in Hindu society, actively engaged in serious religious debates with Christian missionaries in India, and a champion of women’s rights and freedom of press (standing up against colonial censorship). Yet when he went to England he caused some stir as the urbane face of a reforming Indian society, was active in campaigning for the 1832 Reform Act as a step to British democracy. The philosopher Jeremy Bentham reportedly even began a campaign to elect him to the British Parliament (but Roy caught meningitis and died in Bristol soon after).

The western admirers of Amartya Sen as a public intellectual may not be aware that he is actually in a long line of globally engaged cultural elite that Bengal has produced. (This is true to some extent of the elite elsewhere in India as well, particularly around Chennai and Mumbai, but I think in sheer scale over the last two hundred years, Bengal may have a special claim). One aspect of this phenomenon is worth reflecting on. These members of the cultural elite were well-versed in the manifold offerings of the West, but they came to them with a solid grounding in the cultural wealth of India. Take Ram Mohan Roy (1772-1833). He was, as Nehru describes him in his Discovery of India, “deeply versed in Indian thought and philosophy, a scholar of Sanskrit, Persian and Arabic, ..a product of the mixed Hindu-Muslim culture, …the world’s first scholar of the science of Comparative Religion.” He contributed to the development of Bengali prose. He was a social reformer in Hindu society, actively engaged in serious religious debates with Christian missionaries in India, and a champion of women’s rights and freedom of press (standing up against colonial censorship). Yet when he went to England he caused some stir as the urbane face of a reforming Indian society, was active in campaigning for the 1832 Reform Act as a step to British democracy. The philosopher Jeremy Bentham reportedly even began a campaign to elect him to the British Parliament (but Roy caught meningitis and died in Bristol soon after).

The perfect, so the saying goes, is the enemy of the good. Don’t deny yourself real progress by refusing to compromise. Be realistic. Pragmatic. Patient. Don’t waste resources and energy on lofty but ultimately unobtainable goals, no matter how noble they might be; that will only lead to frustration, and worse, hold us all back from the smaller victories we can actually achieve.

The perfect, so the saying goes, is the enemy of the good. Don’t deny yourself real progress by refusing to compromise. Be realistic. Pragmatic. Patient. Don’t waste resources and energy on lofty but ultimately unobtainable goals, no matter how noble they might be; that will only lead to frustration, and worse, hold us all back from the smaller victories we can actually achieve. My eyes traced the 1500-mile-long arc of the Aleutian Range. Running down the Alaskan Peninsula, the land on either side of the mountains is mainly wilderness and wildlife refuges. Even more astonishing was the complete absence of roads. As a Californian that is hard to fathom.

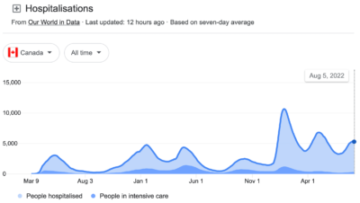

My eyes traced the 1500-mile-long arc of the Aleutian Range. Running down the Alaskan Peninsula, the land on either side of the mountains is mainly wilderness and wildlife refuges. Even more astonishing was the complete absence of roads. As a Californian that is hard to fathom. A mandate isn’t necessarily tyrannical. It’s a rule that, in any good government, is devised to protect the people from harm so we can better live and work together. We must monitor legislation to ensure we stop laws that can harm people, but we also need to get involved when harm comes from a

A mandate isn’t necessarily tyrannical. It’s a rule that, in any good government, is devised to protect the people from harm so we can better live and work together. We must monitor legislation to ensure we stop laws that can harm people, but we also need to get involved when harm comes from a

It’s 1980, I’ve just had my first proper kiss, and the newspapers are announcing the death of love.

It’s 1980, I’ve just had my first proper kiss, and the newspapers are announcing the death of love.