by Raji Jayaraman

In the last two decades the topic of inequality has entered the public discourse across a broad spectrum of issues, with an urgency that is astonishing. To name but a few examples, the Occupy movement has called for more income equality, Black Lives Matter protesters have demand racial equality, women’s advocates have rallied behind causes as varied as equal pay and reproductive rights , and environmental activists have advocated for climate justice.

Surprisingly, economists are not front and centre of this discussion. I say “surprisingly” because economists are supposed to be the experts on inequality: they measure and study it. I think the reason why economists have not played a more central role in this discussion is that the protesters in today’s mass demonstrations are not just pointing out the existence of inequality. They are saying: “inequality is unjust”. With a few notable exceptions, however, today’s empirical economists don’t talk about justice. I fear that if economists don’t incorporate justice into their analysis, they risk losing relevance.

Why don’t applied economists who deal with data and policy design, speak of justice in a meaningful way? I think it boils down to four fundamental axioms that will be familiar to every economist. First, allocations must be efficient. Second, evidence must be data-driven. Third, policies should be forward-looking. Fourth, choices are made “at the margin”. As I explain below, I believe that these are very useful axioms. I also think, however, that they make it very hard for empirical economists who study inequality to effectively participate in the current debate on justice. In what follows, I explain why, using the four examples of protest movements to illustrate the crux of the problem. Read more »

Sughra Raza. Self Portrait in The November Sun, 2020.

Sughra Raza. Self Portrait in The November Sun, 2020.

Going back and reading one’s favorite authors is like seeing an old friend after a long absence: things fall into place, you remember why it is you get along with and like the other person, and their idiosyncrasies and unique character reappear and interact with your own, making old patterns reemerge and lighting up parts of you that have long been dormant.

Going back and reading one’s favorite authors is like seeing an old friend after a long absence: things fall into place, you remember why it is you get along with and like the other person, and their idiosyncrasies and unique character reappear and interact with your own, making old patterns reemerge and lighting up parts of you that have long been dormant. The western admirers of Amartya Sen as a public intellectual may not be aware that he is actually in a long line of globally engaged cultural elite that Bengal has produced. (This is true to some extent of the elite elsewhere in India as well, particularly around Chennai and Mumbai, but I think in sheer scale over the last two hundred years, Bengal may have a special claim). One aspect of this phenomenon is worth reflecting on. These members of the cultural elite were well-versed in the manifold offerings of the West, but they came to them with a solid grounding in the cultural wealth of India. Take Ram Mohan Roy (1772-1833). He was, as Nehru describes him in his Discovery of India, “deeply versed in Indian thought and philosophy, a scholar of Sanskrit, Persian and Arabic, ..a product of the mixed Hindu-Muslim culture, …the world’s first scholar of the science of Comparative Religion.” He contributed to the development of Bengali prose. He was a social reformer in Hindu society, actively engaged in serious religious debates with Christian missionaries in India, and a champion of women’s rights and freedom of press (standing up against colonial censorship). Yet when he went to England he caused some stir as the urbane face of a reforming Indian society, was active in campaigning for the 1832 Reform Act as a step to British democracy. The philosopher Jeremy Bentham reportedly even began a campaign to elect him to the British Parliament (but Roy caught meningitis and died in Bristol soon after).

The western admirers of Amartya Sen as a public intellectual may not be aware that he is actually in a long line of globally engaged cultural elite that Bengal has produced. (This is true to some extent of the elite elsewhere in India as well, particularly around Chennai and Mumbai, but I think in sheer scale over the last two hundred years, Bengal may have a special claim). One aspect of this phenomenon is worth reflecting on. These members of the cultural elite were well-versed in the manifold offerings of the West, but they came to them with a solid grounding in the cultural wealth of India. Take Ram Mohan Roy (1772-1833). He was, as Nehru describes him in his Discovery of India, “deeply versed in Indian thought and philosophy, a scholar of Sanskrit, Persian and Arabic, ..a product of the mixed Hindu-Muslim culture, …the world’s first scholar of the science of Comparative Religion.” He contributed to the development of Bengali prose. He was a social reformer in Hindu society, actively engaged in serious religious debates with Christian missionaries in India, and a champion of women’s rights and freedom of press (standing up against colonial censorship). Yet when he went to England he caused some stir as the urbane face of a reforming Indian society, was active in campaigning for the 1832 Reform Act as a step to British democracy. The philosopher Jeremy Bentham reportedly even began a campaign to elect him to the British Parliament (but Roy caught meningitis and died in Bristol soon after).

The perfect, so the saying goes, is the enemy of the good. Don’t deny yourself real progress by refusing to compromise. Be realistic. Pragmatic. Patient. Don’t waste resources and energy on lofty but ultimately unobtainable goals, no matter how noble they might be; that will only lead to frustration, and worse, hold us all back from the smaller victories we can actually achieve.

The perfect, so the saying goes, is the enemy of the good. Don’t deny yourself real progress by refusing to compromise. Be realistic. Pragmatic. Patient. Don’t waste resources and energy on lofty but ultimately unobtainable goals, no matter how noble they might be; that will only lead to frustration, and worse, hold us all back from the smaller victories we can actually achieve. My eyes traced the 1500-mile-long arc of the Aleutian Range. Running down the Alaskan Peninsula, the land on either side of the mountains is mainly wilderness and wildlife refuges. Even more astonishing was the complete absence of roads. As a Californian that is hard to fathom.

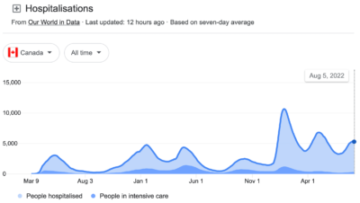

My eyes traced the 1500-mile-long arc of the Aleutian Range. Running down the Alaskan Peninsula, the land on either side of the mountains is mainly wilderness and wildlife refuges. Even more astonishing was the complete absence of roads. As a Californian that is hard to fathom. A mandate isn’t necessarily tyrannical. It’s a rule that, in any good government, is devised to protect the people from harm so we can better live and work together. We must monitor legislation to ensure we stop laws that can harm people, but we also need to get involved when harm comes from a

A mandate isn’t necessarily tyrannical. It’s a rule that, in any good government, is devised to protect the people from harm so we can better live and work together. We must monitor legislation to ensure we stop laws that can harm people, but we also need to get involved when harm comes from a