by Steven Gimbel and Gwydion Suilebhan

For the last several years, elected Republicans, full of anti-trans zeal, have challenged their opponents to define the word “woman.” They aren’t really curious. They’re setting a rhetorical trap. They’re taking a word that seems to have a simple meaning, because the majority of people who identify as women resemble each other in some ways, then refusing to consider any of the people who don’t.

For the last several years, elected Republicans, full of anti-trans zeal, have challenged their opponents to define the word “woman.” They aren’t really curious. They’re setting a rhetorical trap. They’re taking a word that seems to have a simple meaning, because the majority of people who identify as women resemble each other in some ways, then refusing to consider any of the people who don’t.

Lexicographers—the people who put together the dictionaries—care more about words than most of us. Of late, they’ve noticed how their beloved definitions have been abused by conservatives, and now a few have struck back. On December 13, the Cambridge Dictionary broadened their definitions of “man” and “woman” to include people who identify as either.

The original definition of “woman”: an adult female human being.

The new addition to the definition: an adult who lives and identifies as female though they may have been said to have a different sex at birth.

Losing their gotcha question infuriated conservatives. Fox News howled that “this change was met with pushback from many, who argued that redefining society’s categorization of gender and sex is harmful and inaccurate.” Dan McLaughlin, a senior writer at National Review called the change Orwellian: “1984 wasn’t supposed to be a how-to manual,” he tweeted.

Unfortunately for conservatives, they’re wrong. That is precisely how dictionaries are supposed to work. Dictionaries have always been political documents. For that, we have a Founding Father to thank. Read more »

Let’s get the humble-bragging out of the way first: I’ve always had a remarkable memory.

Let’s get the humble-bragging out of the way first: I’ve always had a remarkable memory.

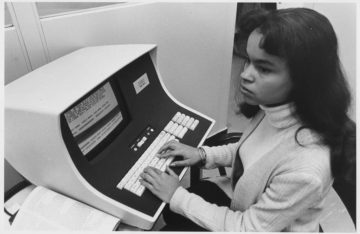

Flor Garduno. Basket of Light, Sumpango, Guatemala. 1989.

Flor Garduno. Basket of Light, Sumpango, Guatemala. 1989.