by Michael Liss

We are all Republicans; we are all Federalists. —Thomas Jefferson, March 4, 1801

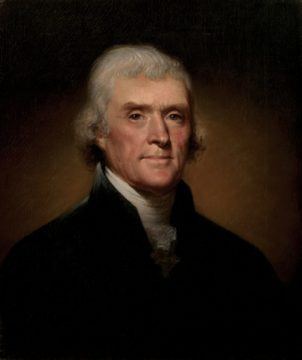

Inauguration Day, 1801. John Adams may have beat it out of town on the 4:00 a.m. stage to Baltimore, but the podium filled with dignitaries, none more impressive than the man taking the Oath of Office. Thomas Jefferson, Poet Laureate of the American Revolution, former Secretary of State, outgoing Vice President, was standing there in all his charismatic glory.

As politicians have done, presumably from time immemorial, he pronounced himself awed by the challenge (“I shrink from the contemplation, and humble myself before the magnitude of the undertaking”), imperfect (“I shall often go wrong through defect of judgment”), and an obedient servant (“[r]elying, then, on the patronage of your good will…”). He made the obligatory bow to George Washington (Adams being absent both corporally and in Jefferson’s spoken thoughts), and called upon the love of country that stemmed from shared experience: “Let us, then, fellow-citizens, unite with one heart and one mind.”

How very Jeffersonian. Inspiring, embracing, collaborative, worthy of his fellow citizens’ admiration and even love. Looking back over 200 years, allowing for the archaic language, and even the sense that this was not his best work, you can still hear in it the echoes of what drew people to him.

Jefferson was more than a symbolic change in direction from the Adams (and Washington) years. He was the physical embodiment of what he later came to describe as the Second American Revolution. The public had cast aside the old Federalism, stultifying and crabbed, with a narrow vision of what democracy meant, and had chosen to move towards the bright light of freedom.

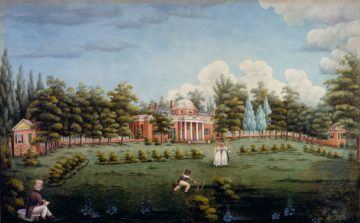

You have to love the story. It fits with an image of Jefferson that many have clung to over the decades. Jefferson was more than a stick figure of stiffly posed portraits, policies, and speeches. He was a full-blooded, passionate person: Jefferson the gourmand; Jefferson the suave raconteur; Jefferson having a grand old time in Paris and at Monticello. He was the courtier abroad, and the master of house and estate at home—his days filled with fine wine, good conversation, books, music, and enchanting women.

This historical version of Jefferson (the image popularized by biographers like Dumas Malone) requires a bit of a filter on the part of the teller—a bit of time spent walling off, explaining away, or even denying some of the less appealing aspects of his life. It is neither wholly accurate, nor how many of his contemporaries viewed him at the time. They saw his flaws, some imagined, many real.

This is not the place to retread that ground. I began this series three months ago talking about partisanship and the emergence of political parties, and Jefferson is the preeminent political party leader of our first half-century. That is the framework I want to use: Jefferson as the co-creator of the Democratic-Republican Party, Jefferson as its first U.S.President, Jefferson (along with Madison) as the molder of an ideology and the prime instrument for amplifying it. So, while not dismissing Jefferson’s myriad defects of character and judgment, I am going to use Garry Wills’ characterization in his book, Negro President (“My Jefferson is a giant, but a giant trammeled in a net, and obliged (he thought) to keep repairing and strengthening the coils of that net.”).

When John Adams got on that pre-dawn stagecoach, the door that closed behind him was also closing on his Federalist Party’s grasp on the Presidency. It’s one of history’s ironies that the last Federalist President wasn’t really a Party man at all. Adams had no interest and certainly no talent for politics the way we understand it. Instead, he had this oddly appealing, yet monumentally impractical, sense that a President should use his best judgment, regardless of the political implications of it. The problem with Adams’ idea as a construct for future Presidents was that Presidents need their Parties to enact legislation, to carry a coherent, unified message, and otherwise to have their backs. The problem the movers in the Federalist Party made for themselves in rejecting Adams, a fellow Federalist, is that they misunderstood the essential connection that the voters make between President and Party. We know this intuitively now…an unpopular President hurts his own team down-ballot. Hamilton (and Timothy Pickering, James McHenry and Oliver Wolcott, his loyalists in Adams’ Cabinet) could not, in their arrogance, recognize that, by undercutting and demeaning Adams, they weren’t showing themselves superior beings worthy of even more power and influence. They were just giving the electorate, such as it was at that time, an opportunity to view them as pompous, aloof, and autocratic.

In fact, the Federalists were pompous, aloof and autocratic. They had largely held their ground in the 1798 Midterms in part because the public approved of Adams’ handling of negotiations with France the previous summer. Unfortunately, the leaders of the Party were unable to see the cause and effect. Adams, they thought, was an apostate to High Federalist dogma—so, never mind that what he had done was both diplomatically and politically effective, it was not what they had counseled, and was thus, by definition, bad.

Still, their continued control of the SIxth Congress and the White House gave them time to recalibrate, and wiser political heads would have recognized the opportunity and acted on it. The American Revolution wasn’t just a liberation from England and King George III. It was also (at least for white men) a liberating moment from the tyranny of being ruled by fiat by the elites. On this, the Republicans offered a clear choice—individual rights as set forth in the Bill of Rights, including the right to dissent, should be sacrosanct. High Federalists were horrified by the idea of too much freedom—what would the common man know about policy? Why should anyone, regardless of his station in life, be permitted to critique them when they were exercising their superior judgment?

To use a modern construct, you don’t say these things out loud, but the Federalists not only did, but used coercion to act on them. They continued to push for Hamilton’s “New Army” even after the threat of outside invasion had subsided; they initiated more prosecutions under the Alien and Sedition Act; and they used disproportionate force in snuffing out “Fries Rebellion” by German immigrants in Pennsylvania. They seemed to have a talent for making new enemies.

What they had missed, what they hadn’t really understood, was that the country was moving into a new century and a new way of thinking. Governments were not permanent; not every well-educated and well-bred man would share their beliefs; and opposition was not treason. Positions of influence often needed to be earned in the marketplace of elections. High Federalists would shudder at the thought of submitting themselves to the judgment of the unlettered and unwashed, but the old paradigm was dead.

Jefferson did understand this, as did Madison, and other politically talented Republicans. Despite Jefferson’s affected stance of being above it all, he actually threw himself into the campaign, if only secretly. Jefferson’s anonymous words found their way into sympathetic publications; his money enabled the dissemination of all types of information (some true, some, decidedly less so); and Jefferson’s private counsel somehow was transmitted to his closest associates.

The Presidential Election itself was close. While Adams and his Federalist ticket (he ran with Charles C. Pinckney) were clearly the losers, Jefferson wasn’t immediately the winner. The public, in addition to broadly supporting Republican candidates, also gave a clear edge to the Jefferson-Burr ticket. The problem was that both men ended up with 73 Electoral Votes, and, before the adoption of the 12th Amendment, that meant they were tied…for the Presidency.

While everyone “knew” Jefferson was at the top of the ticket, the same Constitutional clause that had made Jefferson Adams’ Vice President in 1796 now threw the race into the House of Representatives. There, the Federalists finally woke up and began to act like a Party when they realized they held the balance of power. Jefferson or Burr? Burr was more credible than he might appear today, because this was 1801, before he ruined himself by dueling with Hamilton and then later going off on a wild, arguably seditious ride to form another country in the Southwest. Jefferson, through intermediaries, expected Burr to withdraw. Burr stayed coy…he did, after all, have the same number of votes (and, he might have reminded Jefferson, was instrumental in snatching New York for them, right under the eyes of Hamilton).

This left Jefferson apoplectic. Why should the defeated Federalists choose anything? He began to talk of it as a legislative “usurpation” and even to whisper about armed resistance if the House went for Burr.

Jefferson or Burr? Pick your poison? Or, more accurately, what could be bartered in exchange for the Oval Office? Burr, to his immense credit, refused to offer what the Federalists really wanted, and what Adams had previously asked of Jefferson—job security for at least some of their appointees in the next Administration and a pledge not to dismantle Adams’ robust Navy. Burr then absented himself from Washington altogether, going to New York for a daughter’s wedding.

If Burr wouldn’t commit, but also wouldn’t withdraw, what then? Through 35 ballots and feverish, behind-closed-doors discussions presumably fueled with alcohol and cigars, strange bedfellows, odd alliances, half-promises, murmured commitments, and some actual integrity, a Federalist Congressman from Delaware, James Bayard, voted for Jefferson and made him President. What induced Bayard to get on board, especially as he was thought to have favored Burr personally? Two things, one known, and one unknown. The known is that Burr finally relinquished his claim to the Presidency prior to the 36th vote (Bayard considered him a fool for doing so). The unknown is just what, if anything, Jefferson (or, more likely, people acting with Jefferson’s authorization) promised Bayard and the Federalists.

On February 16th, it was over, and the House chose Jefferson, which certainly seemed the intent of the public. Adams prepared to go home. As outgoing Presidents do, Adams was leaving a mixed bag of issues and gifts for his successor. His most valuable present was his late-in-term diplomatic triumph/treaty with the French.

As an astute reader of last month’s post pointed out, the story of the rocky relationship between the United States and its erstwhile ally merits far more attention than I have given it. Suffice to say that the conduct of the French towards American shipping ranged from merely predatory actions to those that might reasonably be thought of as acts of war. Resolving this, deftly and with tact, as Adams did, was of particular value to Jefferson and Republicans in general. Their Francophile leanings had led them to be tolerant of French overreach and critical of Federalist attempts to protect American interests. With this threat neutralized, Jefferson could avoid direct confrontation at the outset of his presidency and instead focus on cutting an immensely beneficial deal for the Louisiana Territory.

But Adams (and the Federalists) also gave Jefferson both a headache and a political opening. The lame duck session of Congress produced the Judiciary Act of 1801, which, for all its questionable antecedents, was critically important. The Act created 16 districts, which, in turn, were organized into six circuits, sparing Justices of the Supreme Court the necessity of riding circuit. It also, not so coincidentally, created 16 Judicial vacancies, which Federalists urged Adams to fill promptly. These before-he-got-on-the-stagecoach “Midnight Appointments” were a source of rage for Republicans, who had no intention of letting Federalist judges get in the way of their ambitions for Jefferson’s first term.

Jefferson knew this when he rose to speak. It, and the topic of Federalist holdovers would be the first test of his political skills, his newly assumed dual role as President and Party leader, and perhaps even his integrity.

The public had chosen. In the second contested election this country had experienced, the voters selected the Republicans over the Federalists. They weighed two different ideologies, two different futures, and picked the one they preferred, opting to change course. As for Jefferson, and whatever promises he may have made to secure his election, it’s fair to say that “We are all Republicans; we are all Federalists” was the highwater mark of bipartisanship in his Presidency.