by Tim Sommers

What’s the greatest prediction of all time?

By “greatest,” I mean something like how big a deal the thing predicted is multiplied by how accurate the prediction was. I would love to hear other proposals in the comments, but mine is Andy Warhol’s prediction that, “In the future, everyone will be famous for 15 minutes.”

It was made somewhere around 1968. Not only were there no social media and no internet at the time, but computers were barely even a thing. Could you have looked around at celebrity culture in 1968 and predicted Instagram and Twitter and influencers?

Yes, I know. Many doubt that Warhol said this. Wikipedia, for example, baldly asserts that this quote is “misattributed” to Warhol, while the Smithsonian Magazine more judiciously reports that he “probably never said” that. But I don’t think the evidence that they cite really confirms their skepticism. The Smithsonian Magazine, for example, reports that art critic Blake Gopnik (never even mentioned as one of the suspects in the Wikipedia article) claimed credit for the quote, and then they take it as confirmation of Gopnik’s story that later on Gopnik also said that he (Gopnik) heard Warhol say that he (Warhol) never said that. It’s like Wittgenstein’s example of someone trying to confirm what’s in the newspaper by buying a second copy of the same newspaper. Yoko Ono, John Lennon, and David Bowie all credit the quote to Warhol. That’s good enough for me.

On the other hand, maybe the fact that it’s hard to figure out to whom to attribute the quote, works better for our subject. Which is this. ‘If the medium is the message,’ as media theorist Marshall Mcluhan said, ‘what is the message of the internet as a medium?’ (Mcluhan, despite being an academic, became so widely recognize, largely for that line, that he did a cameo as himself in Annie Hall.)

My philosophy training forces me to begin by saying that I think Mcluhan should have said, ‘The medium of any particular media technology is itself also itself a kind of message in addition to the particular messages merely conveyed by that medium…” (Or something like that.)

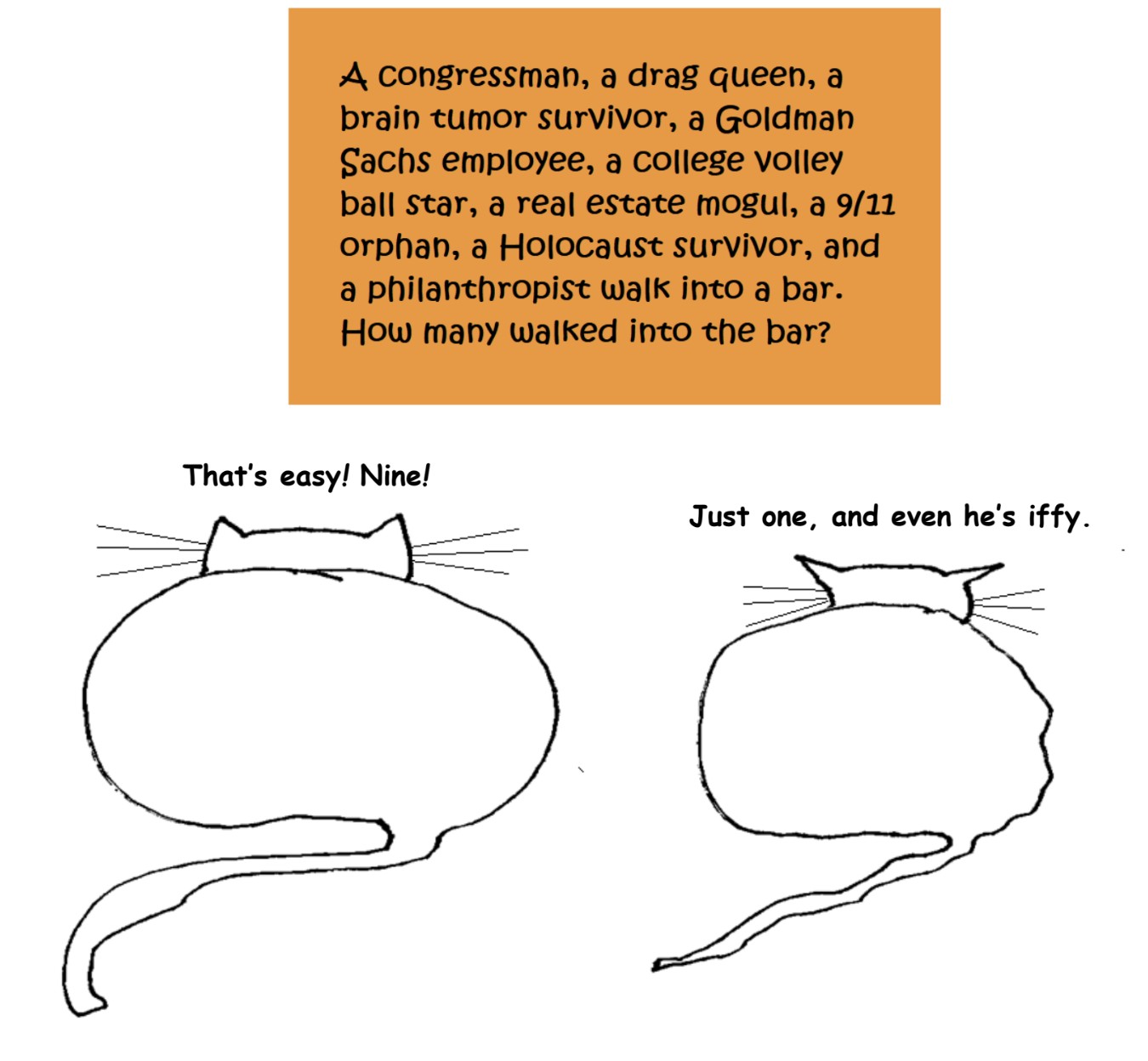

Anyway, what is the message of the internet as a medium? The techno Utopian message of the internet, according to early enthusiasts, is that, “Information wants to be free.” Unfortunately, that’s wrong. The real message of the internet is, “All information is equal.” Read more »

Ada Beams. Landscape Somewhere in France, 2022.

Ada Beams. Landscape Somewhere in France, 2022.

I’m scared of birds. They’re dinosaurs, you know. They descend from the Jurassic when, just like in Jesus Loves Me, ‘they were big and we were small.’ Did you see those huge

I’m scared of birds. They’re dinosaurs, you know. They descend from the Jurassic when, just like in Jesus Loves Me, ‘they were big and we were small.’ Did you see those huge  Lots of people discredit the Myers-Briggs as just a horoscope, but it’s

Lots of people discredit the Myers-Briggs as just a horoscope, but it’s

Sughra Raza. Early Winter Shapes, January 2022.

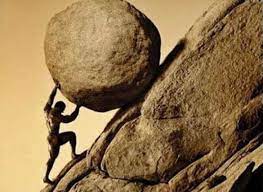

Sughra Raza. Early Winter Shapes, January 2022. If we are to believe the most prominent of the writers we now lump under the category of “existentialism,” human suffering in the modern world is rooted in nihilism. But I wonder whether this is the best lens through which to view human suffering.

If we are to believe the most prominent of the writers we now lump under the category of “existentialism,” human suffering in the modern world is rooted in nihilism. But I wonder whether this is the best lens through which to view human suffering.

Blanchett’s performance has been much praised, and it is indeed a tremendous thing: she must be near the head of the queue for an Oscar this year. It’s a great performance in a genuinely worthwhile and absorbing film. I don’t think it really expands our understanding of the themes it features: power and the exploitation young hopefuls by the (seemingly) all powerful star, the question of great art and flawed artists and so on, but it’s possible to come out of the movie thinking that it has. Blanchett’s performance has a lot to do with that. So a great performance in a very good rather than great film (assuming such categories can really be employed so neatly).

Blanchett’s performance has been much praised, and it is indeed a tremendous thing: she must be near the head of the queue for an Oscar this year. It’s a great performance in a genuinely worthwhile and absorbing film. I don’t think it really expands our understanding of the themes it features: power and the exploitation young hopefuls by the (seemingly) all powerful star, the question of great art and flawed artists and so on, but it’s possible to come out of the movie thinking that it has. Blanchett’s performance has a lot to do with that. So a great performance in a very good rather than great film (assuming such categories can really be employed so neatly).

In

In