by Tim Sommers

My wife Stacey is irritated with the way Netflix’s machine learning algorithm makes recommendations. “I hate it,” she says. “Everything it recommends, I want to watch.”

On the other hand, I am quite happy with Spotify’s AI. Not only does it do pretty well at introducing me to bands I like, but also the longer I stay with it the more obscure the bands that it recommends become. So, for example, recently it took me from Charly Bliss (76k followers), to Lisa Prank (985 followers), to Shari Elf (33 followers). I believe that I have a greater appreciation for bands that are more obscure because I am so cool. Others speculate that I follow more obscure bands because I think it makes me cool while, in fact, it shows I am actually uncool. Whatever it is, Spotify tracks it. The important bit is that it doesn’t just take me to more and more obscure bands. That would be too easy. It takes me more and more obscure bands that I like. Hence, it successfully tracks my coolness/uncoolness.

The proliferation of AI “recommenders” seems relatively innocuous to me – although not to everyone. Some people worry about losing the line between when they just like what the AI recommends to them, and when they adapt to like what the AI says they should like. But that just means the AI is part of their circle of friends now, right? It’s the proliferation of AIs into more fraught kinds of decision-making that I worry about.

AIs are used to decide who gets a job interview, who gets granted parole, who gets most heavily policed, and who gets a new home loan. Yet there’s evidence that these AIs are systematically biased. For example, there is evidence that a widely-used system designed to predict whether offenders are likely to reoffend or commit future acts of violence – and, hence, to set bail, determine sentences, and set parole – exhibits racial bias. So, too several AIs designed to predict crime ahead of time, to guide policing (a pretty Philip K. Dickian idea already). Amazon discovered, for themselves, that their hiring algorithm was sexist. Sexist, racists, anti-LGBTQA+. anti-Semitic, and anti-Muslin language is endemic among large-language models. Read more »

There was a period in my life when I believed that all humans came from one man. This included his wife Eve. After that followed a period when I believed nothing and I thought that was enough.

There was a period in my life when I believed that all humans came from one man. This included his wife Eve. After that followed a period when I believed nothing and I thought that was enough. Does philosophy have anything to tell us about problems we face in everyday life? Many ancient philosophers thought so. To them, philosophy was not merely an academic discipline but a way of life that provided distinctive reasons and motivations for living well. Some contemporary philosophers have been inspired by these ancient sources giving new life to this question about philosophy’s practical import.

Does philosophy have anything to tell us about problems we face in everyday life? Many ancient philosophers thought so. To them, philosophy was not merely an academic discipline but a way of life that provided distinctive reasons and motivations for living well. Some contemporary philosophers have been inspired by these ancient sources giving new life to this question about philosophy’s practical import. Wendy Red Star. Winter – The Four Seasons Series, 2006.

Wendy Red Star. Winter – The Four Seasons Series, 2006.

Soon after the pandemic commenced its

Soon after the pandemic commenced its  There was a time when Google replied with images of and information about a world-class jockey, an Englishman born the same year Mark Twain published

There was a time when Google replied with images of and information about a world-class jockey, an Englishman born the same year Mark Twain published  This year marks the 42nd anniversary of the American release of The Hitchhikers’ Guide to the Galaxy. Douglas Adams’ “five-book trilogy,” of which Hitchhiker’s was the first installment, led readers through a melancholy universe in which bureaucracy is the ultimate source of evil and shallow, self-serving incompetents are the galaxy’s greatest villains. The best-selling series helped shape the worldview of Generation X, capturing the nihilistic cynicism of the Thatcher/Reagan 1980s.

This year marks the 42nd anniversary of the American release of The Hitchhikers’ Guide to the Galaxy. Douglas Adams’ “five-book trilogy,” of which Hitchhiker’s was the first installment, led readers through a melancholy universe in which bureaucracy is the ultimate source of evil and shallow, self-serving incompetents are the galaxy’s greatest villains. The best-selling series helped shape the worldview of Generation X, capturing the nihilistic cynicism of the Thatcher/Reagan 1980s.

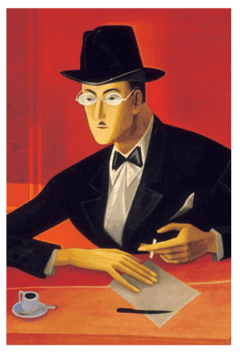

Senhor Soares goes on to explain that in his job as assistant bookkeeper in the city of Lisbon, when he finds himself “between two ledger entries,” he has visions of escaping, visiting the grand promenades of impossible parks, meeting resplendent kings, and traveling over non-existent landscapes. He doesn’t mind his monotonous job, so long as he has the occasional moment to indulge in his daydreams. And the value for him in these daydreams is that they are

Senhor Soares goes on to explain that in his job as assistant bookkeeper in the city of Lisbon, when he finds himself “between two ledger entries,” he has visions of escaping, visiting the grand promenades of impossible parks, meeting resplendent kings, and traveling over non-existent landscapes. He doesn’t mind his monotonous job, so long as he has the occasional moment to indulge in his daydreams. And the value for him in these daydreams is that they are

Sughra Raza. Chughtai In Shabnam’s Living Room, November, 2022.

Sughra Raza. Chughtai In Shabnam’s Living Room, November, 2022.

I moved to Berlin in 1984, but have rarely written about my experiences living in a foreign country; now that I think about it, it occurs to me that I lived here as though in exile those first few years, or rather as though I’d been banished, as though it hadn’t been my own free will to leave New York. It’s difficult to speak of the time before the Wall fell without falling into cliché—difficult to talk about the perception non-Germans had of the city, for decades, because in spite of the fascination Berlin inspired, it was steeped in the memory of industrialized murder and lingering fear and provoked a loathing that was, for some, quite visceral. Most of my earliest friends were foreigners, like myself; our fathers had served in World War II and were uncomfortable that their children had wound up in former enemy territory, but my Israeli and other Jewish friends had done the unthinkable: they’d moved to the land that had nearly extinguished them, learned to speak in the harsh consonants of the dreaded language, and betrayed their family and its unspeakable sufferings, or so their parents claimed. We were drawn to the stark reality of a walled-in, heavily guarded political enclave, long before the reunited German capital became an international magnet for start-ups and so-called creatives. We were the generation that had to justify itself for being here. It was hard not to be haunted by the city’s past, not to wonder how much of the human insanity that had taken place here was somehow imbedded in the soil—or if place is a thing entirely indifferent to us, the Earth entirely indifferent to the blood spilled on its battlegrounds.

I moved to Berlin in 1984, but have rarely written about my experiences living in a foreign country; now that I think about it, it occurs to me that I lived here as though in exile those first few years, or rather as though I’d been banished, as though it hadn’t been my own free will to leave New York. It’s difficult to speak of the time before the Wall fell without falling into cliché—difficult to talk about the perception non-Germans had of the city, for decades, because in spite of the fascination Berlin inspired, it was steeped in the memory of industrialized murder and lingering fear and provoked a loathing that was, for some, quite visceral. Most of my earliest friends were foreigners, like myself; our fathers had served in World War II and were uncomfortable that their children had wound up in former enemy territory, but my Israeli and other Jewish friends had done the unthinkable: they’d moved to the land that had nearly extinguished them, learned to speak in the harsh consonants of the dreaded language, and betrayed their family and its unspeakable sufferings, or so their parents claimed. We were drawn to the stark reality of a walled-in, heavily guarded political enclave, long before the reunited German capital became an international magnet for start-ups and so-called creatives. We were the generation that had to justify itself for being here. It was hard not to be haunted by the city’s past, not to wonder how much of the human insanity that had taken place here was somehow imbedded in the soil—or if place is a thing entirely indifferent to us, the Earth entirely indifferent to the blood spilled on its battlegrounds.