by Thomas O’Dwyer

“There is no question I love her deeply … I keep remembering her body, her nakedness, the day with her, our bottle of champagne … She says she thinks of me all the time (as I do of her) and her only fear is that being apart, we may gradually cease to believe that we are loved, that the other’s love for us goes on and is real. As I kissed her she kept saying, ‘I am happy, I am at peace now.’ And so was I.”

These romantic diary entries of a middle-aged man smitten with a new love would seem unremarkable, commonplace, but for one thing. The author was a Trappist monk, a priest in one of the most strict Catholic monastic orders, bound by vows of poverty, chastity, obedience and silence. Moreover, he was world famous in his monkishness as the author of best-selling books on spirituality, monastic vocation and contemplation. He was credited with drawing vast numbers of young men into seminaries around the world during the last modern upsurge of religious fervour after World War II. Two years after this tryst, the world’s most famous monk was found dead in a room near a conference centre in Bangkok, Thailand. He was on his back, wearing only shorts, electrocuted by a Hitachi floor-fan lying on his chest. In the tabloids there were dark mutterings of divine retribution, suicide, even a CIA murder conspiracy.

So passed Thomas Merton, who shot to fame in 1948 when he published his memoir The Seven Storey Mountain. It was the tale of a journey from a life of “beer, bewilderment, and sorrow” to a seminary in the Order of Cistercians of Strict Observance, commonly known as Trappists. A steady output of books, essays and poems made him one of the best known and loved spiritual writers of his day. It also made millions of dollars for his Trappist monastery, the Abbey of Gethsemani in Nelson county, Kentucky. Because of him, droves of demobbed soldiers and marines clamoured to become monks.

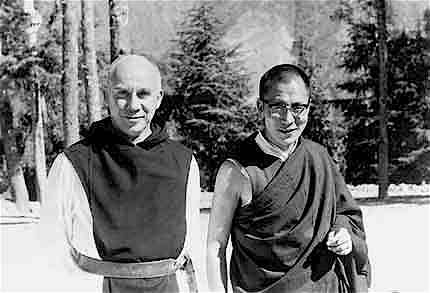

Merton still has a considerable following among the spiritually inclined and they seem little troubled by the human failings of a supposedly cloistered contemplative monk. Pope Francis spoke about Merton with enthusiasm when he addressed the US Congress in 2015: “Merton was a man of prayer, a thinker who challenged the certitudes of his time and opened new horizons.” But, for one of his biographers, Mark Shaw, Merton was a troubled “imposter of sorts.” Shaw’s Beneath the Mask of Holiness portrayed Merton as a reluctant monk donning the persona of a happy, contemplative guru, a Catholic Dalai Lama. Shaw claimed that Merton could never reconcile his youthful past of drinking and skirt-chasing with his new saintly image, so his lapse back into the arms of a 25-year-old woman when he was 51 could be seen as inevitable. Merton’s fans say that to condemn a man for the sin of falling in love is to attack the very humanity and passion that made him a great spiritual guide for ordinary people. They say this humanity does not make him any less holy. One reviewer of Shaw’s book wrote, “In Merton, one sees both the sins and the sanctity. And I wonder if this isn’t the way God sees us.”

The dichotomy between those who revere saints and those who rail against their hypocrisy is as old as religion itself — which is to say, as old as the human race. In the modern (Western) world where the old religions would appear to be in rapid decline, battles between believers and scoffers still rage on. A recent clash of Christian ideas between the American political left and right seems downright medieval to bemused Europeans. Democratic presidential aspirant Pete Buttigieg and Vice President Mike Pence are both from Indiana’s evangelical heartland but might live on different Christian planets. “The thing I wish the Mike Pences of the world would understand, that if you’ve got a problem with who I am, your problem is not with me,” the gay and married Buttigieg told his followers recently. “Your quarrel, sir, is with my creator.”

Both sides cleave to the same dark-skinned Jewish Middle Easterner, Jesus of Nazareth, but portray him as some pale US mid-westerner with a designer beard. Pence’s evangelical right claims a monopoly on morality, Buttigieg’s Christian left (if it exists) prefers social justice and inclusiveness. The right prefers to ask “what would Jesus do?” — about guns, gays, abortions, immigrants — rather than read what he actually said — about the rich, the poor, the children, women, the Other. In that context, it seems fair to assume that Jesus would opt to be Buttigieg’s campaign manager rather than Pence’s.

A new biography, On Thomas Merton, by Mary Gordon, marking 50 years since he died, suggests that The Seven Storey Mountain was not a book but a phenomenon. However, the real phenomenon, of which Merton was one part, was the religious renaissance that swept America in the years after World War II, before it began to fizzle with the advent of a new war, Vietnam, in the 1960s. In 1956, “In God We Trust” was adopted as the US national motto, replacing the unofficial “E pluribus unum” (From many, one), which had been adopted with the Great Seal in 1782.

The fervour was decidedly Christian — at a stretch, perhaps Judaeo-Christian. Post-war opinion polls revealed that pastors, priests and rabbis were the most respected leaders of society. The “three great religions” of the period were Protestantism, Catholicism and Judaism and of these, the most morally powerful for a period was Catholicism. The Jewish theologian and sociologist Will Herberg actually wrote a book titled Protestant, Catholic, Jew in 1955. He suggested that immigration and American ethnology were reflected in the country’s religious movements and in the influential position of Judaism. However, as in public consciousness, Islam was still invisible in his book, as were Hinduism, Buddhism and the rest. Herberg, a former Marxist, famously claimed that anti-Catholicism was the antisemitism of secular Jewish intellectuals — although it was equally virulent among non-Catholic Christians.

In a 21st century of declining church-going, there is now some irony in the fact that one of the strongest religious prejudices remaining (in America at least) is against the non-believer. Opinion surveys continue to show that the atheist is a despised outcast, a person not fit for society and (God forbid) most certainly not fit to be president of the USA. Attacks on atheists from the religious right actually treat atheism as if it were itself a religion — a “wrong” religion, of course, like Catholicism used to be. Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris and Christopher Hitchens have been mocked as wild-eyed prophets of this atheist creed. The evolutionary biologist David Sloan Wilson (an agnostic) described the new atheism of Dawkins and his posse as a “stealth religion”. This was because it also seemed to assert its own truth and righteousness as beyond denial and its enemies as “bad, bad, bad.”

It is futile to point out that since theism means “yes, god,” so atheism must mean “no god.” If not believing in gods is a religion, then not playing basketball is a sport. And yet, many people with no religion, particularly agnostics, do find the arrogance of atheist “missionaries” very annoying. The label of atheist itself is problematic — “I know for certain there is no creator” proclaims absolute knowledge of the fact. The label “agnostic” more humbly states, “I don’t have the knowledge that would allow me to reach a definite conclusion.” Agnosticism seems more in tune with scientific reasoning and open-mindedness — “I don’t believe there is a supreme being, but if you can come up with some evidence, even if it takes a few more millennia, we’ll examine it.”

Ah, science. And religion. It’s a match made in hell, an unstoppable force meeting an immovable object. Galileo still (allegedly) mutters “e pur si muove” (and yet it moves), while the pope, like a medieval Seinfeld, counters, “Did you say something? I know you said something. What did you say?” Galileo could well have added, by the way, that religion doesn’t exist, that it’s not a thing, but a syndrome, a complex of symptoms. First, you need a set of creation myths; add to that some afterlife inventions and some arbitrary social rules. Roll all these into a few artificial rituals sanctioned by magical or miracle edicts and lo, thou hast a religion. All you need now is a flock of credulous and deluded followers and you’ve got yourself either a new church or The Life of Brian.

“Agnosticism is of the essence of science, whether ancient or modern,” wrote Thomas Huxley, the British anthropologist who was known as “Darwin’s bulldog” for his vigorous defence of the theory of evolution. “It simply means that a man shall not say he knows or believes that which he has no scientific grounds for professing to know or believe.” Agnostics are rarely hostile to religion as a cultural reality. They concede that in addition to the sins and atrocities religion has inflicted on humanity — the Inquisition, missionaries, pogroms and 9/11 — it has also given us the music of Bach, algebra, astronomy, Michelangelo and Byzantium. More precisely, the sins and benefits have not been delivered by an abstract syndrome called religion, but by real people who have been inspired — or led astray — by their personal beliefs. Art crafted by Christians would have been made by the same persons were they not Christians, just as Greek art was inspired by the non-existent pantheon of irascible deities, and Hindu art by a handful of their 330 million gods.

Considering they lay claim to eternal truths, religious believers are pretty dim when it comes to spotting trends that threaten their smug certainties. Judging by the universal hatred for atheists in America, it is clear the religious fear atheism as the wrecking ball of belief. What they have failed to notice for centuries is that atheism is not the enemy, but science. A person who doesn’t believe doesn’t care; a person who doesn’t know really does care. There’s an anecdote about someone asking a Jewish philosopher if he was an atheist and being told: “Well, I no longer believe in Zeus and now I’m working on Yahweh.” In 399 BCE, Socrates was tried and found guilty of both “corrupting the minds of the youth of Athens” and of “not believing in the gods of the state.” Yes, that’s 2,400 years ago, a philosopher was executed for atheism — or, more accurately, for agnosticism. (Socrates, who claimed to know nothing, was too wise to claim certainty on anything). The gods were already dying at the hands of natural philosophy, as early science was called.

And yet they are still with us. So atheists too have been equally dim in predicting the end of religion under the steamroller of rationalism and science. As the divine residents of Mount Olympus faded away, along came Jesus and his father (and semi-deified mother). And after him, Muhammad, who re-introduced Jesus’ dad El, swapping his Hebrew for Arabic, and becoming Al. One of the most stunning resurrections of religion in modern times came after the fall of the communist bloc in 1989. Much of the world assumed that the atheistic communist regimes had stamped out religion in the countries they had controlled for 70 years. Elimination of religion had been an ideological objective of ruling political parties. Yet, almost immediately after the fall, the Orthodox clergy emerged from the shadows and thousands of churches began to reopen and fill with worshippers.

Those hoping for the demise of religion in a large area of the world were confounded; the new atheists were left with nothing but their rage. One large battle may have been lost, but the war between reason and belief is far from over. The fundamentalists may not have noticed, but science is once again creeping up on them, like a big cat in the long grass. Some recent articles on religion in New Scientist magazine, of all places, show those sneaky scientists honing in on the question of why the human brain evolved a need for religious belief. There is a chink in the armour of religious certainty, and that is its tendency to define gods as those who do all the things the scientists can’t explain. We don’t understand how the big bang created the universe. Oh, God did that! We don’t know how evolution started. Yeah, easy, God did it. We don’t know why our brains need gods. Oops!

Now, the gods used to be responsible for a lot of things – light and dark, the heavens, creation, creatures and humans, history itself – they were all there in the holy texts. Unless one is a Bible literalist, and not many modern Christians or Jews are (not even the pope), the religious are left with a god of shrinking spaces. The more we understand through scientific exploration, the less there is that we can claim for a god’s supernatural intervention. Yes, Galileo was correct, the earth still moved, whatever the pope said in the name of his god of an earth-centric universe. Neither does the sun come up because Apollo hauls it in his chariot across the sky.

No scientist thinks that for something we don’t know, a god did it. All it really means is we need some more research to find out about the thing we don’t know. And the more we learn, the less there is for the god of unsolved mysteries to claim. The god probably will be always with us, getting smaller, but still curating what happened before the big bang, claiming his magic created some fork in the evolutionary tree, his gullible followers screeching, “See, you don’t know everything that God does.” True, but we’re learning what he didn’t do, and there’s a lot of it.

So what is he good for? Not a lot, and that’s the real eternal truth.