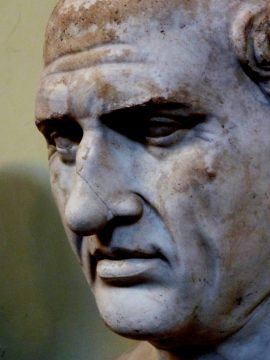

by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

Cicero’s philosophical dialogues are notoriously difficult. In some cases, as with the Academica and the Republic, their fragmentary state exacerbates the challenge of interpretation. In other cases, as with On Ends, the breadth of the discussion makes it difficult to locate the thread. In every case, Cicero stays true to his Academic skeptical training of opposing every argument with another argument. In some instances, one line of reasoning comes out clearly best, but in others, it is not so clear. And then there is On the Nature of the Gods. It is a special case. Let us explain.

The overall structure of On the Nature of the Gods is quite simple. The theologies of three philosophical schools are represented, each with a Roman mouthpiece. Epicureanism is represented by Velleius, Stoicism by Balbus, and Academic skepticism by Cotta. Cicero writes himself into the dialogue, too, as listening in and promising not to tilt the verdict in favor of his fellow Academic, Cotta. Velleius proceeds to give an outline of Epicurean theology, complete with an account of how it is possible to know things about the gods, what the gods are like, and how we should live in light of these truths. In short, Epicureans believe that we know about the gods because we have deeply held conceptions of them, which must have antecedent causes. The gods have human bodies and they live lives free of care for eternity. Consequently, we should not fear the gods, because they take no notice of us. Cotta the Academic skeptic then proceeds to demolish the Epicurean case. Why trust preconceptions when they are so often wrong? If the gods have human-like bodies, how can they be immortal? And if the gods don’t care about us, then what’s the point of religion or piety at all? Isn’t Epicureanism really just atheism? Read more »