by Thomas O’Dwyer

“There is no question I love her deeply … I keep remembering her body, her nakedness, the day with her, our bottle of champagne … She says she thinks of me all the time (as I do of her) and her only fear is that being apart, we may gradually cease to believe that we are loved, that the other’s love for us goes on and is real. As I kissed her she kept saying, ‘I am happy, I am at peace now.’ And so was I.”

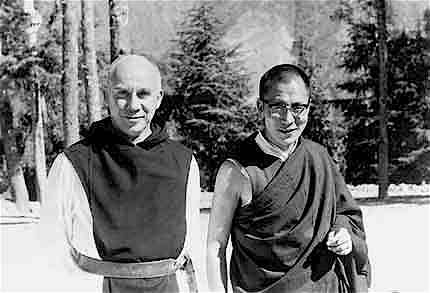

These romantic diary entries of a middle-aged man smitten with a new love would seem unremarkable, commonplace, but for one thing. The author was a Trappist monk, a priest in one of the most strict Catholic monastic orders, bound by vows of poverty, chastity, obedience and silence. Moreover, he was world famous in his monkishness as the author of best-selling books on spirituality, monastic vocation and contemplation. He was credited with drawing vast numbers of young men into seminaries around the world during the last modern upsurge of religious fervour after World War II. Two years after this tryst, the world’s most famous monk was found dead in a room near a conference centre in Bangkok, Thailand. He was on his back, wearing only shorts, electrocuted by a Hitachi floor-fan lying on his chest. In the tabloids there were dark mutterings of divine retribution, suicide, even a CIA murder conspiracy.

So passed Thomas Merton, who shot to fame in 1948 when he published his memoir The Seven Storey Mountain. It was the tale of a journey from a life of “beer, bewilderment, and sorrow” to a seminary in the Order of Cistercians of Strict Observance, commonly known as Trappists. A steady output of books, essays and poems made him one of the best known and loved spiritual writers of his day. It also made millions of dollars for his Trappist monastery, the Abbey of Gethsemani in Nelson county, Kentucky. Because of him, droves of demobbed soldiers and marines clamoured to become monks. Read more »