by Jalees Rehman

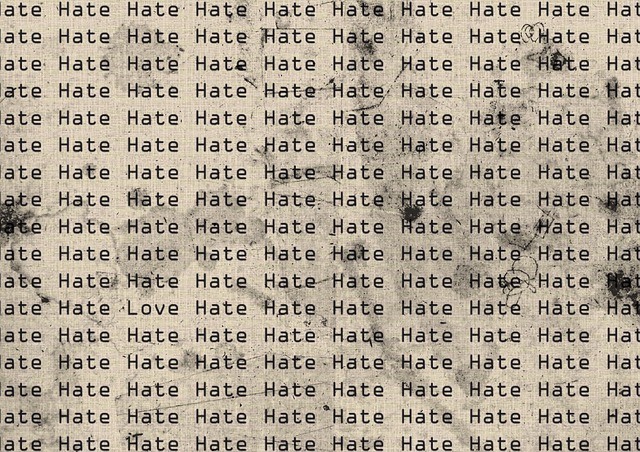

How should social media platforms address hate speech and abusive comments while also maintaining a commitment to freedom of expression? The platform Twitter, for example, evaluates whether posts by individual users constitute abusive behavior, which it defines as “an attempt to harass, intimidate, or silence someone else’s voice”. Twitter’s rationale is that promoting dialogue and freedom of expression requires that all of its users need to feel safe in order to express their opinions, and that abusive posts by some users may undermine the safety of others. If users engage in abusive behavior, they may be asked to remove offensive posts, and if there is a pattern of recurring abusive posts, the offenders may be temporarily or permanently suspended. This rationale sounds quite straightforward, especially when a user specifically threatens or incites violence against other individuals. However, if the offenders post hateful comments denigrating members of a gender, race, sexual orientation or religion without specifically threatening individuals, then it becomes challenging to demonstrate that the victims of such hate speech are less safe. What is the impact of hate speech? Researchers have begun to address this important question and their results highlight the dangers of unfettered hate speech.

Dr. Wiktor Soral from the University of Warsaw in Poland and his colleagues recently conducted multiple studies to investigate the impact of hate speech on shaping prejudice and published their findings in the paper Exposure to hate speech increases prejudice through desensitization. In the first study, the researchers examined the views of adult Poles (computer assisted face-to-face interviews of 1,007 participants, mean age 46 years) in regards to prejudice against Muslims and members of the LGBT community because both of these groups are frequently targeted by hate speech in Poland. Participants were first given a list of anti-Muslim and anti-LGBT hate speech examples such as “I am sorry, but gay people make me feel disgusted” or “Muslims are stinky cowards, they can only murder women, children and innocent people.” The researchers were asked to rate these statements on a scale of 1 to 7, from “Not at all offensive” (1) or “Strongly offensive” (7). The researchers then asked the participants how often they heard anti-LGBT and anti-Muslim hate speech. Lastly, the researchers then assessed the prejudice level of the participants by asking them to rate whether they would (or would not) accept a member of the Muslim or LGBT communities as a co-worker, a neighbor, or as part of their family.

The researchers found that participants who were more frequently exposed to hate speech against minorities, had a higher likelihood of exhibiting anti-Muslim or anti-LGBT prejudice. Interestingly, the analysis of their data suggested that this increase in prejudice was linked to a lower sensitivity towards assessing the hate speech examples as offensive. Soral and colleagues interpreted this as a “desensitization” process. If one gets inundated with hateful comments against minorities, one no longer perceives them as offensive and this ultimately leads to an increase in prejudice targeting minorities.

The research team then undertook a second study in a different group of participants (682 Polish adolescents, ages 16-18) and expanded their focus to include anti-immigrant and anti-refugee prejudice. The set-up of the study was quite similar to the prior study in the older participants but the hate speech examples provided to the participants included specific comments targeting refugees such as “Let the refugees arrive to our country. What else will you burn in power plants? The rest of them you can always redo into dog food.” The assessment of prejudice was expanded to specifically ask whether the participants endorsed anti-immigrant policies such as “Due to the refugee crisis, the government should allow uniformed services to use direct coercion and violence against refugees”. As in the prior study, the participants who exhibited the most prejudice were most likely to be regularly exposed to hate speech and they were also least likely to consider hate speech as being offensive. This again supported the notion of “desensitization”, however, as with the other study, it was difficult to draw definitive causal inferences. Did the regular exposure to hateful comments lead to desensitization and more prejudice? Or are individuals with greater anti-minority prejudice more likely to seek out hate speech comments?

To definitely establish a cause-effect relationship between exposure to hate speech and its impact on prejudice, the researchers then conducted an experimental intervention. They studied 76 Polish undergraduate students who were told they were participating in a study on web design and memory. Unbeknownst to them, they were divided into two groups, and each group was given multiple pages of online comments to read (approximately 6 minutes of reading) that mimicked comments one would find on social media. The control group participants read general political or societal comments such as “the further we will keep that state from our homemade windmills and panels, the better. First it was to supplement and then the horrendous taxes.” The other group read hateful comments targeting Muslims, LGBT community members as well as other minorities which are commonly targeted in Poland such as Jews, Gypsies and Ukrainians such as “I still think that the gypsies are thieves and sluts, members of the mafia and organized crime in theft and begging”.

The researchers then assessed the level of prejudice in the participants and their assessment of how offensive they would classify hate speech comments. The findings were quite remarkable. Just a few minutes of reading hateful comments increased the prejudice levels in the group which read the hateful online comments and it also decreased their assessment of how offensive the comments when compared to the group which read neutral political comments. When the researchers analyzed their data in a manner correcting for the sensitivity to hate speech, they no longer found a difference in the prejudice level, thus suggesting that the increase in prejudice was indeed related to decreased sensitivity.

The experiment with the students exposed to standard versus hateful comments is the most interesting experiment conducted by the researchers because it suggests that a brief, well-defined intervention (exposure to online comments) can indeed alter sensitivity and prejudice. A limitation of the data presented is that it was not clear whether reading hateful comments targeting any one group would also increase prejudice against other minorities. It is very likely that the sample size of participants would need to be much higher in order to perform such an in-depth analysis. Another limitation of the study is that the observed effects on prejudice and sensitivity towards hate speech were statistically significant but quite modest in size. However, considering that this was such a brief exposure to hateful comments, it is not a surprise that the effects were not that large in magnitude. A study with repeated exposure to hateful comments over time may have resulted in even greater desensitization and increase in prejudice, and such a study would approximate the real world situation where one is repeatedly exposed to hateful comments.

The research by Soral and colleagues on hate speech desensitization should sensitize us about the dangers of hate speech. The omnipresence of social media provides immense opportunities to those who want to engage in hate speech. If the desensitization theory holds true, then extremist political and religious groups can bring about a change in their audience’s perception of what is hateful by repeatedly broadcasting hateful messages until they represent a new normal, and increase prejudice against minorities. Freedom of expression is a value that many of us cherish but we also need to be aware of how are minds can be manipulated by those who abuse this freedom.

Reference

Soral, W., Bilewicz, M., & Winiewski, M. (2017). Exposure to hate speech increases prejudice through desensitization. Aggressive Behavior, 44(2), 136-146.