by Thomas O’Dwyer

With most of the planet under curfew, now might be a good time to ask, where’s my freedom of choice suddenly gone? Who (or what) determined, in some detail, how billions of us should act and behave for the foreseeable future? A troublesome ancient duo has returned – free will and its shady evil twin determinism. By coincidence, they came eerily embedded in a new Apple TV science-fiction series, Devs, of which more soon. I didn’t choose to be “cocooned” (and I’m sure I can’t opt to re-emerge as a pretty butterfly). However, I do choose to write this article and could equally decide not to. Or could I? The editor sent me a reminder that he was expecting it, so I can’t not write it. Why not?

What can I make of these decisions emerging out of the blue, which I appear to act upon “freely?” What are the consequences of how I choose to react to them? Although these are vague philosophical musings, let’s look instead at the science of it all. I’m a layman, neither scientist nor philosopher, but as we are rediscovering, scientists are a less fuzzy lot than philosophers. I’m more likely to ask the woman with the medical degree about the true meaning of my dry cough than to ask philosopher Slavoj Žižek to waffle incoherently about it for 20 minutes. Science observes events and facts and examines the connections between them. Certain phenomena seem to occur together in a sequence.

What can I make of these decisions emerging out of the blue, which I appear to act upon “freely?” What are the consequences of how I choose to react to them? Although these are vague philosophical musings, let’s look instead at the science of it all. I’m a layman, neither scientist nor philosopher, but as we are rediscovering, scientists are a less fuzzy lot than philosophers. I’m more likely to ask the woman with the medical degree about the true meaning of my dry cough than to ask philosopher Slavoj Žižek to waffle incoherently about it for 20 minutes. Science observes events and facts and examines the connections between them. Certain phenomena seem to occur together in a sequence.

An hour ago I felt my reading glasses slip, tried to grab them, knocked over a cup which splashed coffee on the sleeping cat. Startled, it jumped to a shelf, dislodged an untidy pile of books which crashed to the floor and the cat fled from the study. It took a few seconds, and stasis returned – but the universe is forever changed. Each event in the sequence “caused” the other. This is a scientific fact easily grasped by the layperson, but such things give philosophers nightmares and more opportunities to tie themselves in convoluted knots. And theologians … no, let’s ignore them entirely.

You may bury a seed under damp soil, and sometime later you will find a small green plant in the same place. The seed caused the plant, but how? Scientists will seek to plot each step in that mysterious process, not from idle curiosity, but for knowledge that will allow them to understand it, replicate it, improve it. After an airplane crash, meticulous experts will seek to unravel a chain of events and aim to prevent any future accidents from the same stream of causation. In these cases, success is measured in predicting the future – if we can predict, perhaps we can control. In the case of the plant, we may predict its growth or how much food a field of it might yield. In the case of the plane, we want to change the future – prevent a similar air accident or, in Boeing’s case, fail to do so.

The streaming TV thriller series Devs which Alex Garland, of Annihilation fame, created and wrote, explores the conflict between determinism and free will. Determinism suggests that everything that happens in the world, and the universe, is based on cause and effect, an ancient and startling theory which deletes all free will. All data exists in the causal chain of events since the big bang and could, in theory, be analysed with a powerful enough computer, just as meteorologists model past and future weather patterns from their enormous data banks. The snag is that the amount of data in the universe is infinite. Devs suggests that a massive quantum computer could use determinism to read enough past data to predict the future and understand history.

As Garland said in an interview, “If you unravel everything about you, about the specifics of you, why you prefer a cup of coffee to tea, then five seconds before you said you’d like to have a cup of coffee, one would be able to predict you’d ask for it … A powerful computer could show the actions of any subject in the past or future.” In one startling scene, as they develop the algorithm, a fuzzy grey image emerges of Jesus on the cross speaking Aramaic. As to the predicted future in Devs – well no, that would be a spoiler. As so often in science fiction, the writers are edging uncomfortably beyond evolving theories in real science and technology. In physics, the laws of the large scale universe are mapped by Einstein’s relativity equations. In the sub-atomic world inside the atom, the spooky uncertainty principle of quantum mechanics reigns supreme.

Scientists have so far failed to reconcile these two different explanations of how the universe works and simply say that they coexist. And then we look at the opposing human-based theories of spooky free will and mechanistic determinism and, er, they somehow coexist. In the inanimate world, mechanical chains of events are more easily analysed with scientific tools. However, move the instruments over to study human behaviour and, as usual, things quickly become messier. Jim didn’t turn up for his wedding, because the car crashed and a stranger took him to a hospital – a straightforward mechanical chain of events. But, he didn’t show up because he realised he didn’t love her, that’s one final cause. In complex events the reasons for decisions may be difficult to distinguish, never mind the fact that humans also lie to researchers, and even to themselves (and fiances) about why they made a decision.

In several experiments where researchers deliberately convinced subjects (mostly students) that free will does not exist, they were startled to discover that the subjects’ moral values often deteriorated. Students became more likely to cheat on exams; other participants committed petty crimes. This underpinned the common assumption that free will is bound up with concepts like praise, blame, justice and morality. If all actions are predetermined, why bother praising, blaming or judging anybody for doing things over which they have no control?

In several experiments where researchers deliberately convinced subjects (mostly students) that free will does not exist, they were startled to discover that the subjects’ moral values often deteriorated. Students became more likely to cheat on exams; other participants committed petty crimes. This underpinned the common assumption that free will is bound up with concepts like praise, blame, justice and morality. If all actions are predetermined, why bother praising, blaming or judging anybody for doing things over which they have no control?

What events in a brain “cause” behaviour? Did they start in the womb, in babyhood, in upbringing? A psychiatrist will try to devise remedial action by deciphering this causal chain of events over an individual’s lifetime. Still, notwithstanding the doctor’s scientific credentials, this incredibly complicated effort can sound more like divination. Science has far less success in explaining human behaviour than it has in deciphering a mechanistic chain of causes; brain and mind science is in its infancy. After the big bang, sub-atomic particles followed mechanical laws that determined bonding, movement, molecules, star and planet formation, galaxies, and biological life. It’s easy to accept, this determined outcome for the universe. But who wants to admit that their daily actions are still determined? This is fiercely resisted by our innate belief that we are the masters of our body’s domains and that our wills are free. My will is free; my actions are determined only by me.

In one of the apocryphal quotes attributed to him, baseball star Yogi Berra is said to have advised, “When you come to a fork in the road, take it!” A friend once told me he remembered the exact moment when a tiny decision changed the direction of his life forever. He was a journalist in his 40s, divorced, settled in London, content. One evening, he attended a couple of embassy receptions and was on his way home when he remembered there was a farewell party for a contact of his, a United Nations official, who was leaving the city. He stopped outside the house, put one foot outside his car door, and just didn’t feel like going into another event. He has that image frozen in his brain – the car door half-open, his shoe on the driveway gravel. Then his conscience pricked – the UN man had been an excellent source and given him many leads. He’d just pop in for 10 minutes to thank him and share a drink. He did so, and as he turned to leave, a woman approached him and said, “You’re that magazine journalist. I like your articles.” An hour later, they left together, and a year later, he was settled with her in a foreign country, learning a new language and making a new life. “The whole path of my life changed when my shoe touched that driveway,” he said. “I made a snap decision, but I’ve always felt it was predetermined somewhere out there, and I jumped onto a new timeline with no choice. I’ve never stopped wondering where the other timeline led to.”

Your assert that you, not the universe, determine your actions. But there’s a spanner in the works, although it’s more often called the ghost in the machine. Mind – that’s the problem. The body is entirely mechanistic – squishy and messy maybe, but still quarks, atoms, molecules and energy fields. And it has no choice; evolution determined its course along with the universe. But in the human mind, thought constructs directions and options, and even its image of the universe. My cat does not have a theory of science or existence, but it seems reasonable to accept that she often acts as she does for specific reasons. I have seen her pause and decide to go in this room or that one, to this dish or that. A tiger or lion chooses the exact prey to attack, and we can even deduce the reason for the selection. Something causes their, and our, actions.

Now we have two narratives, free agency and determined rail tracks – both seem reasonable, and both are at odds, like relativity and quantum mechanics. Why did you do that? Because I wanted to. Sure, there are constraints of law and social convention that rein in free will. I could decide to walk naked down the street – but I probably won’t, for many obvious reasons. I choose to live in a society with various rules that I also accept to observe. I could equally decide to live in a nudist colony to be naked or in a cave to escape social norms. And “caused” can be replaced by “determined” in some cases. Losing my job was determined by the company closing down is different than a departure caused by the boss being a jerk. Where I will be next week is already decided, or at least predicted – at home, because of a pandemic lockdown.

In Devs they attempt to model all causes to make it possible to predict the future and view the past. We can see predictions for the progress of the new coronavirus changing and improving by the hour as more scientific data and computing power is thrown at the models. But complete predictability is a logical impossibility because an infinite bank of data is required. (We should note however that quantum mechanics does not make exact predictions, only probabilities. We can calculate a 90 percent chance an electron will go in one direction and a 10 percent chance it will go the other. It’s not deterministic.) Determinism feels unpleasant because no one wants to believe what they choose is already determined – decided – and must happen. We are fond of our could-have, should-have, would-have choices, and even of our ability to sabotage ourselves with illogical decisions, just for the hell of it or to spite someone else. I will still argue that I own all my choices, options, lies, truths, actions and inactions, all products of my free will.

We can look at this as seen by three different actors. One, the individual, you and me, believe that what we do is free and we could have chosen to do something else. I’m going to lift my right hand; fooled you, I raised my left. Actor number two is someone who is watching your actions. We may think “so what,” but this actor is not passive. Many people are watching what we do to try to predict our behaviour – advertisers, economists, politicians, the Big Brothers of the internet like Facebook, Google and Apple. In an analogy to quantum physics, an active prediction by one of these observers may alter what is being predicted. If an influential investment adviser predicts that tech share prices will rise next week, people will buy tech shares, making it a self-fulfilling prophecy. The third type of observer would be detached and neutral, like an alien or an AI algorithm. It will endlessly analyse people data to see if their actions result from the sum of their nature, history, previous decisions. But again, the number of variables remain infinite and cannot be computed, so objective predictions would never become available.

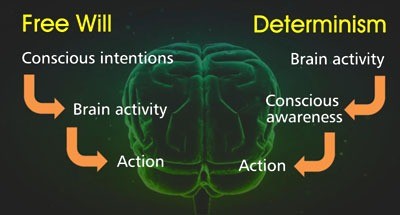

In the meantime, not many people are giving up on free will. This is because of persisting belief in a mind that is separate from the body and the brain. No one expects an MRI scan to image this elusive mind any time soon, but the scans have revealed an intriguing intermediate “mind”. The late scientist Benjamin Libet showed that a region of the brain that coordinates muscle activity fired a fraction of a second before test subjects decided to push a button. The Max Planck Institute updated this landmark experiment and found a vast gap, up to six seconds, between unconscious activity preceding a conscious choice. It seems that conscious decisions are strongly pre-prepared by unconscious brain activity. By the time consciousness fires, most of the work on options has already been done. We could imply that the unconscious brain is the ghostly mind we are seeking. That means the conscious brain is unaware of many of the things going on beneath its surface.

Having come this far, you may think you decided to read it all. No, your brain made the decision long before you even knew about it. How’s your free will looking now? I’m aware that an essay is supposed to round off with a satisfying conclusion, but sorry, I choose not to do that. I’m exiting by the same door I entered, unconvinced. But one thing I do know – I’m keeping a beady eye on those shifty politicians, and when the pandemic finally fades, I am determined to remain free.