by TJ Price

In a 2001 article in The New York Times, Elmore Leonard begins a series of ten rules for writing with “Never open a book with weather.” Whether or not Mr. Leonard is right or wrong in this dictum, I have decided to start this column with exactly that: the weather. My thoughts on such prescriptivist advice aside, nothing so moves me to awe as the aetherial forces constantly swirling both above and around us, informing the very air we breathe and sometimes literally shaping the landscape in which we live. I relish the casual conversations that others dread, in the supermarket and in passing—my forecasts often come from old codgers I happen across: My knee’s singing, they say, pensively. For sure, it’s gonna rain.

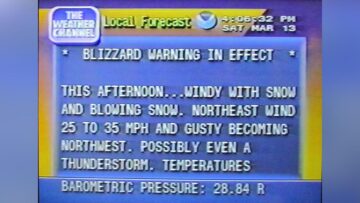

I am relatively sure I inherited this fascination from my mother, with whom I shared an avid love of The Weather Channel, back before it turned into a hopeless amalgam of advertisement and personality. It was with the intensity of sports fanatics that we tracked storms, watching the data go by as a constant cycle of shaded maps and predictions for future precipitation. In hindsight, it’s entirely possible that—due to circumstances of familial uncertainty and confusion at that time—we were attempting to do through forecasting the weather what we couldn’t do with our own lives.

The New England winter was never a question of if, it was always a question of how much, and when. Early mornings consisted of steaming instant oatmeal, orange juice, and the free jazz of The Weather Channel playing over an endless chyron of scrolling school delays and closures. Being that our town was on the farther end of the alphabet, we had to wait through all the Coventries and Middleburys and Tarringtons and Warrenvilles before we got to ours. Despite the anticipation, we were glued to the screen, speculations all based on the data: cold front is moving in quick according to the radar, and look—Tolland is closed, so is Union…

But beyond the winter, and far more exciting—perhaps because it often spun in waters so distant from ours—there was hurricane season: each mysterious, rotating devastator given a name. There was Andrew and Hugo and Bob, each grinding their inexorable way towards us, and we watched every update with anticipation, making predictions. One model said an incoming High pressure was sweeping down from the north, it would push the thing out to sea; another would say this wasn’t the case and the High was being held back by the Low coming up from the southwest—

I often find myself wondering how many people are behind these divinations, the meteorologists who cast their eyes over fluctuating numbers and patterns, their graphs filling with isobars and front lines like occult glyphs, indecipherable to the layperson. I think about how, as a child, I would wander out into the quickly-darkening backyard and stand on a rock while the westerly wind blew all around me. The leaves of the trees would always turn up before a storm, exposing their pale bellies as if they were frightened of the oncoming force—that was how I knew. Projecting much further into the future, despite all the math and machinery, seemed like a losing gamble to me. It seems to me that Nature gives us just enough warning, most of the time—but I was very young, then, and thrived more on the anticipation of fury than on the fear of its disaster.

Since then, technology has given rise to new and more inventive ways of both attempting to control as well as depict in fiction the ravaging effects of inclement weather. Movies regularly involve harrowing scenes of weather-related destruction; some even use this force as primary antagonist, such as Roland Emmerich’s The Day After Tomorrow. Rapid desalinization of the Atlantic from melting polar ice triggers thermohaline disruption, resulting in the generation of massive “superstorms.” The weather itself is portrayed as adversary: plummeting temperatures freeze the unlucky, petrifying them crystalline in a snap. But this is a story of survivors-against-all-odds, and so the humans remain center stage while the winds crack and blow their cheeks around them. The same goes for Twister, also from the 1990s, which foregrounds the tempestuous (sorry) nature of its divorced protagonists against their quest to capture the wind. In this, the wind is savage, remorseless. It dominates the screen, its violence is even felt in the shaky aftermath, but it is the characters we love who are picking through the rubble.

However, George R. Stewart’s fascinating 1941 novel—aptly entitled Storm—does exactly the opposite of both these examples: in it, the titular storm is given a name early on. He calls the wind Maria—specifying in the author’s introduction that it is pronounced ma-RYE-uh—and it is her narrative arc that we follow throughout. Yes, Stewart does also turn his eye (sorry again) to the humans and even the animals affected by Maria, but in a curious choice decides to leave the majority of them nameless. Most of the “characters” in Storm are referred to by their positions: for example, a Junior Meteorologist is called “J.M.” and the Chief Meteorologist is “the Chief”—even their forbear is only referred to as the “Old Master.” In a way, this mythologizes the characters to us, and though many are given idiosyncrasies and peccadilloes, they fade into a kind of archetypal status, functions rendered in a strangely effacing way, as if seen from the perspective of the indifferent storm at the center of the book itself. Indeed, how ants must appear to us, so do these specks of humanity before the terrifying power of nature.

In one particularly harrowing incident on the Eighth Day of the storm—perhaps the most action-packed segment of the book (and there are many)—the Superintendent of Roads strives to keep Donner Pass open to automobile traffic despite blizzard conditions and the tendency of humans to startle in the face of crisis. Failure upon failure mounts, though not just at the Pass, and not just during the storm. Stewart taps into a rhizomatic depiction of humanity at both its best and worst with this novel. While the Superintendent is making critical decisions and the Meteorologists are fretting over what to tell the newspapers, no one person feels more heavily weighted than the other. The character who reigns over the novel is Maria, and she is the centerpiece of this book—all of her eccentricities, her vagaries. Her whims and wishes.

Paralleling this treatment of the human characters, Stewart also portrays most of the events in the story as the consequence of multiple Rube Goldberg devices, further strengthening the inter-connectedness of both the characters and the storm. A stray two-by-four by the side of the road might seem innocuous on the First Day, but add a splat of manure from a passing truck on the Third Day and by the Fourth: disaster. This device is a fitting parallel to the formation of weather in the atmosphere above us. Really, we can perform all the scrying and calculate all the numbers we want, but there is no way to predict what will happen. The air moves as the air will, and we can only prepare for it as much as we can prepare for anything. Hindsight gives us the smart tap of should’ve known better, but does not tell us how to do so for the future—the errant two-by-four could’ve been removed, and would’ve been, if someone had known it would cause tragedy, but the paradox is that, too often, foreknowledge of tragedy is necessary for action to be taken.

In Storm, Stewart is pitiless: both the unnamed and the named alike are obliterated by Maria or its storm-related phenomena. One character even hangs himself at the suggestion that it’ll stay dry—on the Fourth Day, even before the ascension of Maria’s twelve-day reign! Stewart’s seemingly random, picaresque hodgepodge of humanity dips into chaos theory—the butterfly effect can be applied not only to the weather but also in our own society, even strangers on the other side of the world. During the sequence that begins the Superintendent’s ordeal at Donner Pass on the Eighth Day, Stewart takes pains to mention that there is a sign posted on the east slope, before the road steepens. It reads:

STOP

MOTORISTS PUT ON YOUR CHAINS.

WITHOUT CHAINS YOU ENDANGER

YOUR OWN LIFE AS WELL AS OTHERS.

Stewart then notes that:

“Egotists went on ahead, trusting to their own presumed skill as drivers. Optimists assumed that the other fellow would get into trouble. Gamblers enjoyed taking a chance. Plain fools considered that man and his works were superior to the storm. About one car in five on this particular evening went ahead without chains.”

In this simple paragraph, there seems a bit of ominous forecast—perhaps one for our world today, nearly a century beyond the writing of this book. There’s something to be said there for our current stewardship of the planet, I think, regardless. Perhaps also something to be said for how we view the weather, even the very air around us, shared by so many billions just like us and more beside. To wax poetic, we even share our breath with the storms that inevitably descend upon us—a constant cycle of renewal and return, both destruction and the life that springs from the rearrangement of its pieces.

So distant, too, our own concerns can sometimes seem from us. Like gyres in the vast gulf of the future, they are non-threatening until they’re suddenly near enough to turn the leaves belly-up. There may even come a day when there are no trees left to provide such a sign—what divinations will save us then?

I still talk to my mother about the weather more than anything else, I think, outside of internecine squabbling in the family. If there’s a particularly exciting storm heading our way, one or both of us might screenshot the radar and send it in a text. Great big belts of color, inching their amoebic way across the map. (How much they remind me of fMRI animation: activity pulsating in different areas of our brains under stimulus!)

Maybe we knew then, as we do now, that you can’t control the weather, nor predict it. Maybe we only looked forward to drawing in close to one another, away from all the doors and windows, while something else—something vast, unknowable and cosmic—took center stage. Maybe we relaxed knowing that we could not possibly be noticed in the face of such calamity and violence, that we could stop worrying how others saw us, our petty social concerns and status. In the face of the storm, our faces didn’t matter at all—except to those who might grieve at losing sight of them. These we held close, closed our eyes, and breathed; counting one Mississippi, two Mississippi… It was sometimes hard to tell what was worse: waiting for the thunder to roll, or, having heard it, knowing how close the storm really was.

As a child, the storm was fully external, removed from me, thrilling and cinematic. As an adult, it becomes clear that weather is more than just set-dressing—in fact, it informs our every moment in the world. The inverse is true, too, something that is very clear not only in George R. Stewart’s excellent, detailed novel, but also in the modern day narrative of our rapidly-shifting climate. I think we can all agree that our lives are intrinsically bound to this outside force, regardless of politics or geolocation.

I find this truth nowhere more prevalent than in fiction, and Storm serves as twin to the lightning that used to captivate me so much as a child: both delightful entertainment and solemn warning. I don’t know how many Mississippis our modern world has left before the storm hits, but it’s hard to imagine the thunder rolling any louder.

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.