by Ethan Seavey

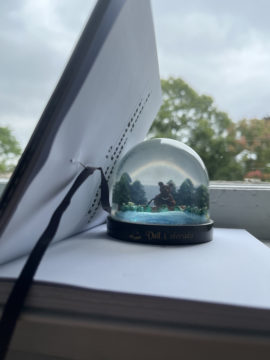

A metal bucket with a snowman on it; a plastic faux-neon Christmas tree; a letter from Alexandra; an unsent letter to Alexandra; a small statuette of a world traveler missing his little plastic map; a snow globe showcasing a large white skull, with black sand floating around it.

A metal bucket with a snowman on it; a plastic faux-neon Christmas tree; a letter from Alexandra; an unsent letter to Alexandra; a small statuette of a world traveler missing his little plastic map; a snow globe showcasing a large white skull, with black sand floating around it.

When I was much younger, there was this vague idea that my death (however randomly it may come about) would result in the total autopsy of my bedroom, which would allow loved ones and biographers the opportunity to analyze my psyche. I planned for them to find my journals and publish my stories posthumously; and it was nice to think about, because I would do none of the work of publishing myself and I would receive all the fame from the grave. For most of the stories I was writing, I would have been similarly satisfied if a thief had stolen them from me to publish under my name while I was still breathing, but as a little boy I had secrets in abundance. It would be absolutely asinine of myself to have secrets lying around my room, ready to be discovered. At least, not without making them work for it first.

One such object is a small book with the title 99. It’s a book you might pick up as a gift for someone you might not know very well. It was given to me by some friends who knew me extremely well and who knew I liked pretty (but practically unreadable) books to leave around as decoration. This book had a pure white cover. Its pages contained 99 “activities” to “do” when you’re bored. Both of these words are in quotes because they wrongly imply that you will be doing something. Some examples: sign up for a class (an activity of waiting which is not immediately invigorating enough to satisfy my boredom); try out an instrument you’ve never played before (an activity I will immediately become discouraged in); set up your single friend with your other single friend (an activity that would not service my own boredom but other people’s).

The one that matters here, though, was a page labeled “flip something familiar upside down.” If you open to the page where the black ribbon sits comfortably, near the middle of the book, you’ll see that the ribbon is fixed with a large sewing pin. Certainly the quest-taker would take notice of this page in particular and realize that it is a clue.

In theory the person would then begin frantically flipping things upside-down. This was the largest hurdle in my plan, I think. There are many little things in my room and all of them are familiar. I imagined detectives flipping everything, my rug, my chair, my bed. I imagined it would leave my room in a state of destruction which would be apt in my absence.

Eventually the detectives would wipe their foreheads with identical white handkerchiefs and suddenly their eyes would lock onto a small snow globe.

It was a souvenir from Vail, Colorado. It houses a very small bear who is fishing in a canoe in a valley of the Rocky Mountains. The detectives would scramble over to the desk and race to flip it over. The one who succeeds is immediately dumbfounded. They share it with their colleagues:

“16 years in here until 10/10/16.”

There are two ways I expected these theoretical personal anthropologists to uncover what this clue meant:

1. They could ask random people about the date until they came across my childhood friend, Rachel, who was the first person I told that I was gay. If by chance she remembers that 10/10/16 was the day I took her to the park right by our grade school late at night, and (over the course of an hour) found the courage to tell her my secret, then they’d be able to guess that I was gay.

2. In their examination of my many Broadway posters, carefully worded journal entries, and notes on my iPad [which were locked by a passcode relating to my favorite book (by then they would know that the most beloved book in the room was I am the Messenger by Markus Zusak, and you’d be able to use the password hint (“playgrounds”) to locate the bookmarked page where the protagonist Ed calls the new playgrounds “plastic vomit,” the true password) — they would have more than enough information to surmise that I was a recently pubescent boy who was probably aware of his sexuality by now, even if he wasn’t telling other people.

Either way, they would realize that I was gay. Therefore my clue implies that I was in the CLOSET for 16 years until 10/10/16. The examiners would then look around the entire closet, searching through boxes and boxes, until they discover the journal I’d hidden between a low shelf and the brackets supporting it. It is my oldest journal. It has little clocks on its surface. Its binding is falling off and its pages are limp. The journal was next to invisible unless you noticed the slight angle of the shelf, which I must say is a worthy trial to determine who may read my private journal.

In the journal, there is much more cryptic information hidden while avoiding certain words, especially the “gay” one, a very short Harry Potter fan fiction, and plot sketches of some ideas I still remember. Maybe the investigators would go on to publish the fanfic, I don’t know. I don’t claim to understand my reasoning. I was a child.

There was no real reason for this secrecy. I was loved and supported. I didn’t think anyone in my home would come in and try to read my journal anyways. No investigator would, either. But it was a delightful little fantasy, to be wrapped up in a story where I become the star with none of the costs or repercussions of stardom.

***

It is summer. I am moving out. I am harvesting the memories I had planted long ago. I received the metal bucket from my grandmother. The neon tree, from Caroline, and it still works. I reread Alexandra’s letter and my unsent letter and I am glad that I did not send it. I put the little traveler in the “throw out/donate” pile. I shake the little skull and watch the black sand settle.

I delay the gratification of beginning the ritual, but eventually, it must start. I know to open the book; I know to flip the snow globe; I know the answer to the riddles; I know the journal’s hiding spot; and, in fact, I know that the journal had already been moved. The secret was out and the autopsy already done. Still, I peek under the shelf. Nothing but old shoeboxes full of objects. They stack high and they smell dusty and their nostalgia is fully consumed.