by Rachel Robison-Greene

When we look back on some of our most pleasant memories, they often share two things in common: people we love and food. We would be unlikely to describe the origin of our favorite meals as food production. We’d be more likely to describe it as cooking and the cooks we’d describe would, invariably be people. That might not always be true.

Mezli was the first fully robotic restaurant in San Francisco. If you stop by for a meal, you’ll find that your fully customizable order is taken by a machine and the food itself is delivered by robots. The creators of Mezli argue that producing food in this way is a moral good: it involves less space, less of a carbon footprint, and has the potential to make food cheaper because there are not employees to pay.

One need not be up for a night out in order for technology to do the cooking. For those who would like some assistance with cooking at home, there’s the Moley Robotic Kitchen. Those who purchase this technology will have a pair of robot arms installed in their kitchens that will prepare and cook food for them. The robot arms can even be trained to cook in the style of the owner’s favorite five-star chefs.

The process of creating food can be time consuming. It can be difficult to find the time and attention every day to craft three healthy and delicious meals for oneself and one’s family. This may be an area in which people could use a little help. On the other hand, we might think that cooking is an art; it’s an aesthetic experience. It is also a fundamental way in which we show love and care to the people in our lives.

AI is already being used to craft recipes; in the future we may not even need to be creative anymore—AI may provide us with more food combinations than we ever considered. It will be able to learn any food tradition and style and will be able to create beautiful and seamless fusions of ingredients. Read more »

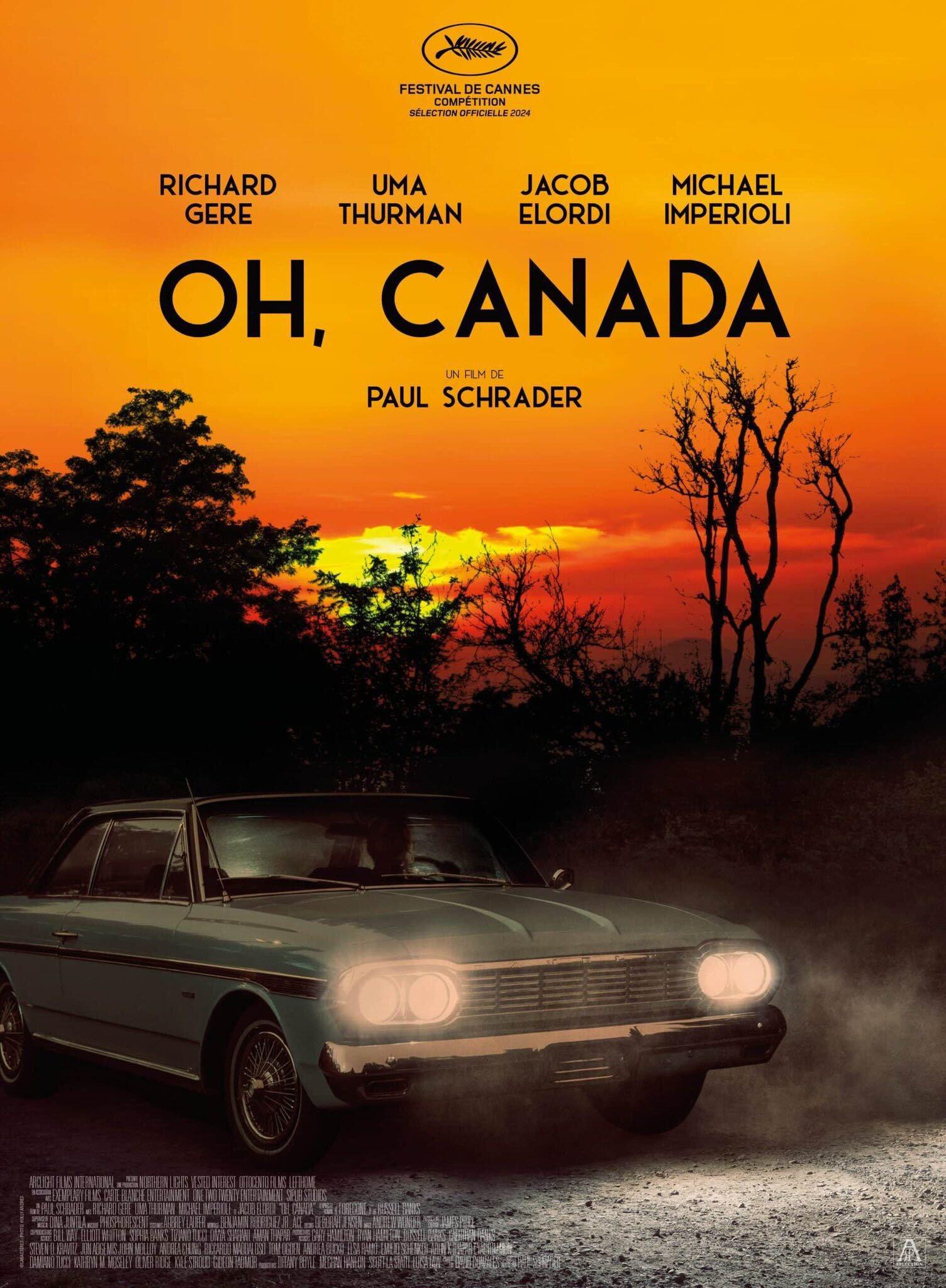

I was in Toronto the other day to see Paul Schrader’s newest film, Oh, Canada, which was screening at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF). This was my first time seeing a movie at a festival, and the experience was quite different from seeing a movie at a cinema: we had to line up in advance, the location was not a cinema but a theatre (in this case, the Princess of Wales Theater, a beautiful venue with orchestra seating, a balcony, and plush red carpeting), and there was a buzz in the air, as everyone in attendance had made a special effort to see a movie they wouldn’t be able to see elsewhere. As I stood in line with the other ticket holders, I noticed that there was a clear difference between the type of person in my line, for those with advance tickets, and the rush line, for those without tickets and who would be allowed in only in the case of no shows: in my line, the attendees were older, often in couples, and had the air of Money and Culture about them; in the rush line, the hopeful attendees were younger, often male, and solitary. In other words, those in the rush line, the ones who couldn’t get their shit together to buy a ticket in time, could have been typical Schrader protagonists: a man in a room, trying, yet frequently failing, to live a meaningful life, to keep it together, to be the type of person who buys a ticket in advance, and invites his wife, too. Yet there I was, in the advance ticket line: a man, relatively young, and someone who spends a good deal of time by himself. I’d invited my partner of 10 years, but she didn’t come because she doesn’t like Paul Schrader films, and who can blame her? They’re not for everyone. Perhaps my presence in the advance ticket line, but my understanding of and identification with those in the other line, helps explain my deep attraction to Schrader’s films: I know his characters, and in the right circumstances, I could become one of his characters.

I was in Toronto the other day to see Paul Schrader’s newest film, Oh, Canada, which was screening at the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF). This was my first time seeing a movie at a festival, and the experience was quite different from seeing a movie at a cinema: we had to line up in advance, the location was not a cinema but a theatre (in this case, the Princess of Wales Theater, a beautiful venue with orchestra seating, a balcony, and plush red carpeting), and there was a buzz in the air, as everyone in attendance had made a special effort to see a movie they wouldn’t be able to see elsewhere. As I stood in line with the other ticket holders, I noticed that there was a clear difference between the type of person in my line, for those with advance tickets, and the rush line, for those without tickets and who would be allowed in only in the case of no shows: in my line, the attendees were older, often in couples, and had the air of Money and Culture about them; in the rush line, the hopeful attendees were younger, often male, and solitary. In other words, those in the rush line, the ones who couldn’t get their shit together to buy a ticket in time, could have been typical Schrader protagonists: a man in a room, trying, yet frequently failing, to live a meaningful life, to keep it together, to be the type of person who buys a ticket in advance, and invites his wife, too. Yet there I was, in the advance ticket line: a man, relatively young, and someone who spends a good deal of time by himself. I’d invited my partner of 10 years, but she didn’t come because she doesn’t like Paul Schrader films, and who can blame her? They’re not for everyone. Perhaps my presence in the advance ticket line, but my understanding of and identification with those in the other line, helps explain my deep attraction to Schrader’s films: I know his characters, and in the right circumstances, I could become one of his characters.

In 1977, I was a student at the University of Pennsylvania, majoring in French Literature. I was 19 years old and pregnant with my first child. I would dress in a long shapeless plaid green and black dress, tie my hair with an off-white headscarf, and wear Dr. Scholl’s slide sandals trying very hard to blend in and look cool and hippyish, but that look wasn’t really working well for me. The scarf at times became a long neck shawl and the ‘cool and I don’t care’ 70’s look became more of a loose colorless dress on top of my plaid dress, giving me the appearance of a field-working peasant. My sandals added absolutely nothing, except making me trip on the sidewalks.

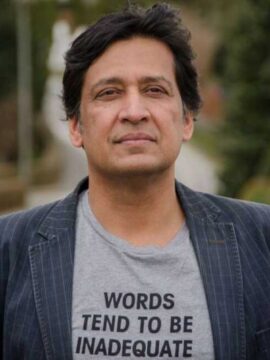

In 1977, I was a student at the University of Pennsylvania, majoring in French Literature. I was 19 years old and pregnant with my first child. I would dress in a long shapeless plaid green and black dress, tie my hair with an off-white headscarf, and wear Dr. Scholl’s slide sandals trying very hard to blend in and look cool and hippyish, but that look wasn’t really working well for me. The scarf at times became a long neck shawl and the ‘cool and I don’t care’ 70’s look became more of a loose colorless dress on top of my plaid dress, giving me the appearance of a field-working peasant. My sandals added absolutely nothing, except making me trip on the sidewalks. The writer Tabish Khair was born in 1966 and educated in Bihar before moving first to Delhi and then Denmark. He is the author of various acclaimed books, including novels

The writer Tabish Khair was born in 1966 and educated in Bihar before moving first to Delhi and then Denmark. He is the author of various acclaimed books, including novels

Sughra Raza. Rain. Hund Riverbank, Pakistan, November 2023.

Sughra Raza. Rain. Hund Riverbank, Pakistan, November 2023.

In the 21st century, only two risks matter – climate change and advanced AI. It is easy to lose sight of the bigger picture and get lost in the maelstrom of “news” hitting our screens. There is a plethora of low-level events constantly vying for our attention. As a risk consultant and

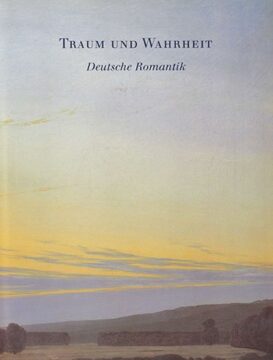

In the 21st century, only two risks matter – climate change and advanced AI. It is easy to lose sight of the bigger picture and get lost in the maelstrom of “news” hitting our screens. There is a plethora of low-level events constantly vying for our attention. As a risk consultant and  The first time I became aware of Friedrich, many years ago, I was in Zurich to meet an elderly Jungian psychoanalyst—my head stuffed with theoretical questions and eerie dreams with soundtracks by Scriabin. Walking down the Bahnhofstrasse, I passed a bookstore window displaying a stunning art book with the elegant title Traum und Wahrheit (Dream and Truth) and a simple subtitle: Deutsche Romantik. I didn’t yet speak German, but I knew enough to be interested. The book was too heavy for my luggage. I bought it anyway and had it shipped.

The first time I became aware of Friedrich, many years ago, I was in Zurich to meet an elderly Jungian psychoanalyst—my head stuffed with theoretical questions and eerie dreams with soundtracks by Scriabin. Walking down the Bahnhofstrasse, I passed a bookstore window displaying a stunning art book with the elegant title Traum und Wahrheit (Dream and Truth) and a simple subtitle: Deutsche Romantik. I didn’t yet speak German, but I knew enough to be interested. The book was too heavy for my luggage. I bought it anyway and had it shipped. What lured my eye to the cover as I passed by was a partial view from one of my now favorite Friedrich paintings, Das Große Gehege (The Great Enclosure)—a cool marshy landscape evoking real ones I would later see from train windows. How could just a corner of a painting have such power? It was the light, the late afternoon saturation of yellow, the black shadowed trees, and the hint of evening gloom already visible as gray on the horizon even though the sky above was still blue. I was captivated.

What lured my eye to the cover as I passed by was a partial view from one of my now favorite Friedrich paintings, Das Große Gehege (The Great Enclosure)—a cool marshy landscape evoking real ones I would later see from train windows. How could just a corner of a painting have such power? It was the light, the late afternoon saturation of yellow, the black shadowed trees, and the hint of evening gloom already visible as gray on the horizon even though the sky above was still blue. I was captivated.

Because I have taken some medical leave from 3QD in the past few weeks, we have not had magazine posts for a while, though we have continued to post curated articles in the “

Because I have taken some medical leave from 3QD in the past few weeks, we have not had magazine posts for a while, though we have continued to post curated articles in the “

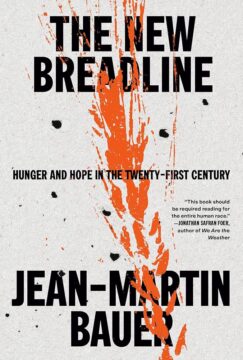

Many decades ago, I was fortunate to have had the opportunity of living in India for several years. I was enthralled by that country: its cultural richness; the environment; the food, but most of all the friendliness and warm hospitality of its diverse people. There were, of course, issues that confounded me and stark contradictions stared back at me from many directions, but of particular concern was the scale of the poverty amongst vast sections of the population, an issue that visited me at home frequently. A small begging community gathered regularly at my front gate, hungry and calling out for food. As my knowledge of the Indian social structure deepened, I came to understand that these people belonged to the most oppressed castes in Indian society and not only they, but a multitude of others were living in poverty, and with hunger.

Many decades ago, I was fortunate to have had the opportunity of living in India for several years. I was enthralled by that country: its cultural richness; the environment; the food, but most of all the friendliness and warm hospitality of its diverse people. There were, of course, issues that confounded me and stark contradictions stared back at me from many directions, but of particular concern was the scale of the poverty amongst vast sections of the population, an issue that visited me at home frequently. A small begging community gathered regularly at my front gate, hungry and calling out for food. As my knowledge of the Indian social structure deepened, I came to understand that these people belonged to the most oppressed castes in Indian society and not only they, but a multitude of others were living in poverty, and with hunger.