by Brooks Riley

Though we are an aggregator blog (providing links to content elsewhere) on all other days, on Mondays we have only original writing by our editors and guest columnists. Each of us writes on any subject we wish, and the length of articles generally varies between 1000 and 2500 words. Our writers are free to express their own opinions and we do not censor them in any way. Sometimes we agree with them and sometimes we don’t.Below you will find links to all our past Monday columns, in alphabetical order by last name of the author. Within each columnist’s listing, the entries are mostly in reverse-chronological order (most recent first).

by Brooks Riley

by Christopher Bacas

Because we remained so long in Housing Court’s trash-strewn orbit, Management assigned us our own agent. Every week, I saw Hassidim in our lobby. One was bigger than the others, with a jellied midsection spilling over pants, bowing his long black lapels. He moved like a man barely acclimated to walking; legs chugging ahead, thighs rubbing, wisps of beard waving cilia-like from his jowls.

To introduce our new handler, Matthew, the property manager, came by. He was a small man who always spoke quickly, words folding back on each other, nervous laughter erasing their authority.

“This is Jo-El. He doesn’t work for me (chuckle, chuckle), the landlord brought him on to work with the building.”

In fact, our landlord’s name was posted on a public list of “New York’s Worst Landlords”. I submitted the open violations in our building to the Public Advocate and within days, his name appeared. The new arrangement was designed to get the owner off that embarrassing list. Jo-El wasn’t a lawyer by training, he was a fixer. His fixing kept broken things broken.

We shook hands. Jo-El didn’t smile. He pressed his lips together and looked down. Read more »

WITHERED ROSE

by Mohammad Iqbal

With what words shall I call you

Desire of the nightingale’s heart?

In a Country of Roses

You were named Laughing Rose

Morning breeze your cradle

Garden a tray of perfumes

My tears rain like dew

And in my barren heart your ruin

An emblem of mine

My life a dream of roses

A reed plucked from its native soil

I sing sweet songs of souls in exile

Translated from the Urdu by Rafiq Kathwari / @brownpundit

by Max Sirak

It turns out you learn a lot when you write a book. This may seem counterintuitive. Perhaps you think, “Well, that’s dumb. If you write a book about something you should already be an expert on it.”

It turns out you learn a lot when you write a book. This may seem counterintuitive. Perhaps you think, “Well, that’s dumb. If you write a book about something you should already be an expert on it.”

That’s a fair way to feel and thing to say.

However, my situation is slightly more unique. See, I don’t write books on subjects I’m an expert in. (I’m not even sure if such subjects exist.) My job as a ghostwriter is to help other people write books in their fields of expertise. It goes like this: most people spend their lives practicing and learning all they can in their fields. Then, after years of gaining proficiency, there almost inevitably comes a time for them to share their hard- won wisdom. The best way to do this, they figure, is to write a book.

That’s where I come in. Usually, the process of becoming a badass in a given field doesn’t entail much writing. Sometimes it does, certainly. But most occupations don’t involve a lot of “writing.” Paperwork? Probably. Reports to fill and file? Likely. But there’s where the pen stops.

So, most folks have spent all their time working toward being the best whatever-it-is-they-are, not writing. I, on the other hand, write every day. Which means, when it comes time for others to share what they’ve learned with the masses, I can help.

And that, friends, is why you are now being treated to a single, kidless guy’s thoughts on parenting. Read more »

by Thomas R. Wells

Tyrants like Vladamir Putin and Kim Jong Un seem to win a lot of their geopolitical contests against democratic governments. How do they do it?

A common explanation is that these tyrants are better at playing the game. They are strategic geniuses leading governments with decades of experience in foreign affairs and characterised by single-mindedness and a long-term horizon. Of course they are going to make better geopolitical moves than democratic governments riven by political factionalism and only able to think as far ahead as the next election.

This explanation is wrong. Tyrants don’t succeed because they are especially skilled at the game of geopolitics, but because they are baddies. Tyrants make bold moves because they are willing to subject their country (and the whole world) to more risk. They can do that because they care less than democrats, and hence worry less, about bringing harms to their people. Like a hedge fund manager, they can afford to take big risks because they are not playing with their own money. When tyrants win it is because of luck, not brilliance. This is easier to see when tyrants lose – as they nearly all do in the end, when their luck runs out.

I. The Clownish Incompetence of Tyranny

The myth of the strategic brilliance of tyrants is driven by cognitive biases. There is the assumption that significant events must have significant agency behind them (the same bias that drives conspiracy thinking). And there is the tendency to fill in the murky mysteries of tyrants’ decision-making by projecting our own worst fears. But if you actually think it through it is rather unlikely that tyrannies would be more competent than democracies, let alone bastions of brilliance. Read more »

I need a good poem

lifespan-short, one

I can shoe-horn between instants

which in that pinch says so much

I’ll understand long and short

by the depth of calluses

they leave on my brain

but it’s not happening

I’m already up to nine lines

so it’s too late for brevity

what I’d like is

one that says something

without rolling on forever

Amazon-like with the

topographical detours

of rivers and streams

or the cul de sacs

of human flaw

but now I see

this is impossible

and won’t end here

in brute summation

like a dead fish

wrapped in newsprint

warning of impending

but once-avoidable

consequence

no, it’ll go on

(who knows why or how long)

until all nouns,

verbs, conjugations,

& absolute clauses

have been spent

until this mine of

memory and metaphor

is no more complete

than the stored meanings,

dragged inside-out

in a flow of pregnant clauses

of blood & breath & bone

that led to others & others & others

like cups spilled into the flow

of the sea-bound flood of

sisters and brothers

Jim Culleny

7/1/18

by Hari Balasubramanian

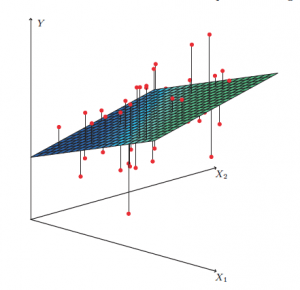

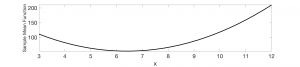

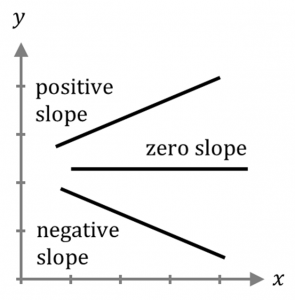

Optimization – the search for the best among many – is at the heart of the statistical and machine learning models that get used so extensively these days. Take the simple concept that underlies many of these models: fitting a mathematical curve to data points, better known as regression. In the simplest two-dimensional case, the curve is a line; in three dimensions, it is a plane, as seen in the figure. Among all possible planes – there are infinitely many of them, obtained by changing the angle and orientation: imagine rotating the plane every which way – we would like the one that passes ‘closest’ to as many of the data points (shown in red) as possible. Thus regression, often called the workhorse of machine learning, is really an optimization problem.

It turns out that optimization is fundamentally connected to even basic statistical quantities. Common statistics we we now reflexively use to summarize data – means, medians and percentiles – are themselves answers to certain optimization questions. We are not used to looking at them in this way.

Let’s take the average or sample mean, which, despite its obvious limitations, everyone turns to first. Suppose we have five numbers in a sample: 3,4,5,8 and 12. The sample mean is given by the straightforward calculation:

(3+4+5+8+12)/5 = 6.4

But there is another way to think of the sample mean: as the optimal answer to the following problem. We seek to find the x that minimizes (produces the lowest value of) the sum of the squared difference between x and each observation in the sample. Mathematically, we can write the function as:

(x-3)2 + (x-4)2 + (x-5)2 + (x-8)2 + (x-12)2

At what value of x does the function have its lowest value? In the figure below, the horizontal axis shows the values that x can take (I restricted myself to the range of the data points, 3 to 12). The vertical axis shows value of the sum of squares function corresponding to each value of x.

We see that the function follows a U-shape with the lowest/best value, x=6.4, occurring at the bottom of the U. Simple high school calculus – finding that point on the continuous curve at which the derivative is 0 – will yield the same answer. In fact, the formula for the mean, adding up all the sample values and dividing by the total number in the sample, can be derived using such calculus. Read more »

by Emrys Westacott

Why do people care about sport? With hundreds of millions of human beings (myself included) obsessively following the world cup that is being played out in Russia, it’s a good time to reflect once again on this perennially interesting question.

Why do people care about sport? With hundreds of millions of human beings (myself included) obsessively following the world cup that is being played out in Russia, it’s a good time to reflect once again on this perennially interesting question.

Of course, it’s also true that hundreds of millions don’t give a damn about sport. I know the type: I’m closely related to a disproportionate number of them. To these people, the passion aroused by twenty-two men in shorts trying to force a ball between two sticks is a great mystery, and not something they find it easy to respect. In their view, even if they don’t say this out loud, getting all worked up over a soccer match is a) dumb, and b) good evidence that one needs to get a life. And they may be right. But that still leaves the phenomenon of sport-induced passion unexplained.

Since it is arguably the sporting event that occasions the most consuming passions, let’s focus on the world cup (although many of the points made will naturally apply to other sports also). And let’s distinguish, at the outset, between enjoyment and passion.

Why is soccer entertaining?

It isn’t so hard to understand why soccer provides enjoyable entertainment. First, and most obviously, a good match is dramatic; it has a compelling narrative. But unlike a play or a film, it is unscripted, which means the outcome is not determined in advance, and that makes a game genuinely exciting. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Holly Case and Lexi Lerner

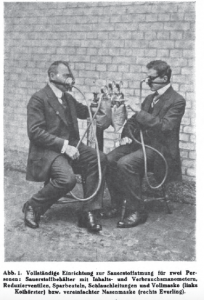

What follows is part of a collaborative project between a historian and a student of medicine called “The Temperature of Our Time.” In forming diagnoses, historians and doctors gather what Carlo Ginzburg has called “small insights”—clues drawn from “concrete experience”—to expose the invisible: a forensic assessment of condition, the origins of an idiopathic illness, the trajectory of an idea through time. Taking the temperature of our time means reading vital signs and symptoms around a fixed theme or metaphor—in this case, the oxygen mask—to reveal how our everyday, recorded interactions can acquire extraordinary historical momentum.

“Among the various exploits, vital or destructive, which oxygen can perform, we varnish makers are interested above all in its capacity to react with certain small molecules such as those of certain oils, and of creating links between them, transforming them into a compact and therefore solid network.” —Primo Levi, The Periodic Table (1975)

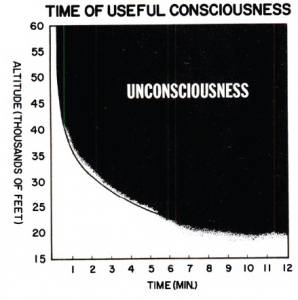

“[A]t 40,000 ft, people have as little as 18 seconds of ‘useful consciousness’ time if they are starved of oxygen. […] [T]he risks of hypoxia–oxygen starvation–are all the greater as people may not realise they are suffering until they can no longer breathe and fall unconscious …” —Lizzie Porter, “What happens when a plane loses cabin pressure?” The Telegraph (Feb. 3, 2016)

“‘Put on your own mask before helping someone else.’ […] I believe this is a metaphor for life.” —Paul Dodd, “The Metaphor of the Airplane Oxygen Mask,” Modern Enlightenment [blog] (May 16, 2015)

***

“Before the oxygen apparatus was used I used to suffer a great deal from flying at high altitudes. […] I used to get this palpitation of the heart and headache when I would fly over 16,000 feet; I would also feel ‘rotten and done up,’ […]” Air Service Medical, War Department, Air Service Division of Military Aeronautics (1919) Read more »

.where are you

…on the willow-hung swing

…in a goldfield of grass

where

…in the hemlock

…straddling the branch just below the top

…hands sticky with sap

where, where

…sitting on the well-house step

…with the lake at your back

…remembering a future

…of victory or collapse

where

…on the topside deck above the bridge

…holding the cable-rail fast

…exhilarated at how the bow’s pitch feels

…spearing a new wave’s gut

…as green water breaks over steel

…and you feel up your spine

…the meaning of

…………………….….….splash!

…among zucchini

…grubbing for ones green and fat

…or off in a high in a twelve-string cage

…hoping to harmonize with truth in that

where

…are you tumbling up a shaft

…like a 9-lived cat

Jim Culleny

6/18/18

by Michael Liss

Let’s talk about bullets and ballots.

First, a thought experiment. Your son is about to become a father for the first time, and you want to get him something special. You have great memories of taking him hunting when he was a boy. So you go to a local gun show, and, at a booth manned by an old friend, you see a real beauty. He’s about to ring you up when something flashes on his screen.

“I can’t sell this to you…it looks like you haven’t bought a gun in at least six years.” He calls over someone official-looking; a long discussion ensues, including a certain amount of hand-waving, but the result is the same. No sale. Several years ago, your State Legislature, concerned about people getting their permits in-state and then moving elsewhere, had sent out postcards to those permit-holders who hadn’t bought a gun in the previous two years to make sure they still resided in the state. You could have responded to the instructions on the postcard, or simply bought a new gun from a licensed dealer in the four years that followed. But you didn’t—in fact, you don’t even remember getting the postcard, much less hearing that not returning it could be a problem.

Tough luck, especially when Democrats took back both the State House and control of the State Legislature. The dealer explained to you that you hadn’t lost your Second Amendment rights—no one was going to touch the guns you already owned or stop you from carrying or hunting—but until you updated your paperwork, the State assumed you had moved and the dealer was prohibited from selling something new to you. He was incredibly apologetic; your boys had played Little League baseball together; he’d even worked for your Dad when he was in high school; so there was absolutely no doubt in his mind that you were who you said you were, and lived where you said you lived, but the law was the law. On this one day, not forever, but this day, you couldn’t purchase that particular gun. He’d put it aside for you, and, as soon as you got off the “No Buy” list, you could have it. Read more »

by Richard Passov

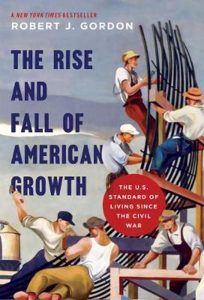

Robert Gordon is the Stanley G. Harris Professor of Social Sciences at Northwestern University. In a well-received book, The Rise and Fall of American Growth, Gordon ‘…contributes to resolving one of the most fundamental questions about American economic history’ by providing ‘… a comprehensive and unified explanation of why productivity growth was so fast between 1920 and 1970 and so slow thereafter.’

The ability to control electricity so that it arrives in measured doses where and when needed combined with simple steps to improve public sanitation, such as running water, indoor toilets and the removal of the uncountable tons of horse manure that marked major cities before the advent of the internal combustion engine that spurred roads and transportation networks that enabled frozen food to be enjoyed from coast to coast, wrought a step change in living standards unlikely to be repeated.

The ability to control electricity so that it arrives in measured doses where and when needed combined with simple steps to improve public sanitation, such as running water, indoor toilets and the removal of the uncountable tons of horse manure that marked major cities before the advent of the internal combustion engine that spurred roads and transportation networks that enabled frozen food to be enjoyed from coast to coast, wrought a step change in living standards unlikely to be repeated.

Economists know the growth in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in any period. And total hours worked and the change in capital. They apportion contributions from labor and capital to GDP based on the amounts of income they ascribe to labor and capital. What remains – the residual that’s necessary to arrive at the total growth in GDP – is Total Factor Productivity (TFP). You can think of this as conflating, in the measured period, smarter workers working harder with more and better capital. Or as one equation with three unknowns.

Going into WWII, TFP was elevated: jobs were scarce and to remain in business, an enterprise had to be extremely productive. During WWII, as Gordon points out, Government built an enormous amount of plant and equipment that was retooled to meet the pent-up demands of a population starved for consumer goods. So no great surprise that the US continued to benefit from surging TFP post WWII.

Since 1970, according to Gordon, TFP has been missing. I know where some of it can be found.

* * *

Recently, I spent a few hot days in Phoenix Arizona at the Bondurant School of driving.

On our first morning, three instructors perched on a table at the front of the class. Will was the lead. For the next few days I’d hear his flat delivery coordinating track time over the radio. Tyler, boyish and rail-thin, was assigned to Camaro drivers. The third instructor approached my group. “Well,” he said, “you guys must be here for the Corvette class. I’ll be working with you. ” Read more »

by Akim Reinhardt

“It’s a long, long way from the Trump administration to an actual fascist dictatorship,” I said, “but it’s a straight line.”

“It’s a long, long way from the Trump administration to an actual fascist dictatorship,” I said, “but it’s a straight line.”

Although generally reserved, Julius (I’ll call him) belly laughed a good while at that, his outburst fueled by personal experience. He’d spent his childhood in General Francisco Franco’s fascist Spain. Specifically in Catalonia, that provincial hotbed of resistance during the Spanish Civil War, and target of fierce repression for nearly nearly four decades following. Franco’s authoritarian rule was ruthless: censorship; banning opposition parties; prisons full of Catalan political dissidents; some four-thousand Catalans executed from 1938-53; thousands more in exile.

Julius deeply loathes Donald Trump. But he also has no patience for hyperbolic claims that El Trumpo is a dictator. Because he knows better. Read more »

by Leanne Ogasawara

Why would she do it?

Maybe she wanted to give the middle finger to her husband?

Maybe she wanted to send a sign to his base voters?

Why didn’t someone stop her from wearing a jacket that said, “I really don’t care.”

It was all another day of Trump TV. Another day when all eyes were on Trump. Another day when headlines ran with his name splashed across the front page all over the world. Another day when memes were shared on Facebook and twitter. And another day people expressed feeling incredibly offended over and over again.

It was all another day of Trump TV. Another day when all eyes were on Trump. Another day when headlines ran with his name splashed across the front page all over the world. Another day when memes were shared on Facebook and twitter. And another day people expressed feeling incredibly offended over and over again.

Another day indeed–as this came on the heels of what was already a big week at Trump TV, given that the star of the show had just surprised all his viewers with news that he was stepping in to solve the problem of the detained children. Yes, he was solving a problem that he had himself created. The only possible way he could get more media attention after creating the problem was by inexplicably solving the problem, pretending that he had no idea why any of this had happened… And then the jacket.

The jacket was good for two full days at least. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Bill Benzon

We are now less than a year away from the scheduled release of Disney’s live-action remake of Dumbo, the studio’s fourth animated feature. It is in some ways dark and sinister–animals jaded from the daily grind of performing and being on display; cruel, exploitive, and drunken clowns; and the snobbish elephant matrons who ostracize Dumbo and his mother. But let’s set that aside–I’ve covered it all, and more, in my working paper on Dumbo. By the time the film had come out, 1941, there’d been a substantial history of cartoons centered on animals. If anything, cartoons were more likely to center on humans than animals. Why animals and why elephants? Read more »

by Maniza Naqvi

Give me a break I mutter. I text—and I text. Incessantly I text. Send money. Now. Send money. More money. You don’t reply. You will. It is Spring and I am young. Everyone around me on the beach is around my age or younger. We are young.

Give me a break I mutter. I text—and I text. Incessantly I text. Send money. Now. Send money. More money. You don’t reply. You will. It is Spring and I am young. Everyone around me on the beach is around my age or younger. We are young.

I offer: Let’s chat. Then I wait. Stretching out leisurely I see stretching before me powdery pristine white sand, waves gently furling and unfurling, nibbling at the beach as far as my eyes can see—a cloudless blue sky mirroring a gentle ocean to my right. A gentle ocean—its blue so blue against the sky and the white that I cannot even give it a name—this blue—this blue of abundance. This blue of calm and peace. This blue of happiness. This combination of blue and white—this perfect sweet air, a fresh ocean breeze. And I am high, feeling the buzz—of this intoxicating time. The beach vibrates—undulates and shivers—trembles with life, the shells, clams and crabs– alive. On the distance horizon over the ocean I can make out cargo ships, probably Chinese and Dutch and trawlers, probably Japanese, netting the big fish. Our fish. Read more »