by Gabrielle C. Durham

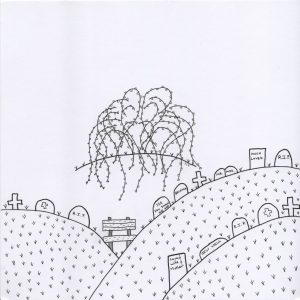

Grief

by Londiwe Buthelezi

It rips through your body.

Grazing, raking, shaving away all the

protective layers you put up all those years before.

layers you used to cover all the pain

you couldn’t possibly show to others.

Grief exposes you.

shows everyone what you really are like inside.

raw and helpless…

I always thought the term “crossing the rainbow bridge” to describe a pet’s dying sounded goofy. People use it in a non-silly way, so good on them for making that work. When we refer to people who die, we use euphemisms, such as Aunt Gigi “passed” or Uncle Gogo is “gone.” It’s too difficult to say, “Grandpa died.” Go ahead, say it out loud to people, and see what happens. Everyone freezes or turns away or starts to cry. “Dead” is too direct. There’s no escaping its frigid finality.

What is grief? According to this study, it is defined as “a normal, healthy, healing and ultimately transforming response to a significant loss that usually does not require professional help, although it does require ways to heal the broken strands of life and to affirm existing ones.” It is a negative reaction to a loss. At some point, we will all grieve, whether it’s for a parent, sibling, child, spouse, friend, pet, relationship, body part, object, or national figure.

What do we say when we grieve? Some of us clam up and say nothing, processing all that has been lost in whatever way we can manage. We all know the bromides that people, ourselves included, spew. “[Person you love] is in a better place” might be the most odious phrase ever. A runner-up is “Everything happens for a reason.” But we can’t help it. We do not know what to say when confronted by pain, so we say something we would never think of uttering in any other circumstance, lower our eyes, and move on quickly to brush off so much grief-lint. I haven’t been to funerals in other countries, but I imagine it’s relatively universal that everyone is uncomfortable until food or drink is served, until some distraction presents itself. Read more »

As a child, I feared dogs. A neighbor kept his German Shepherds, Heidi and Sarge, in a large pen along the alley. The yard and house, his parents’, were the biggest for many blocks. On the alley side, the chain link fence stood 10 feet. The dogs would charge out of their houses silently and hurl their bodies at the fence snarling and barking. I was caught unaware at the fence a few times. My stomach curdled and legs buckled. My mother’s family are dog people. My grandparents cared for a series of large overfed dogs who cavorted in the swamps surrounding their Massachusetts home and otherwise slumped under the kitchen table waiting for my grandmother to put together meals of breakfast scraps bound with maple syrup or for treats from a cookie jar on her counter. My uncles had shambling dogs who would leap into rough water off Cape Cod to retrieve balls from seaweed choked waves. As their fur dried, they smelled of sour salt water and general funk. At the rented house, they showed a gentle deference to humans and lolled on the grass or carpet while my cousins and I ate and talked.

As a child, I feared dogs. A neighbor kept his German Shepherds, Heidi and Sarge, in a large pen along the alley. The yard and house, his parents’, were the biggest for many blocks. On the alley side, the chain link fence stood 10 feet. The dogs would charge out of their houses silently and hurl their bodies at the fence snarling and barking. I was caught unaware at the fence a few times. My stomach curdled and legs buckled. My mother’s family are dog people. My grandparents cared for a series of large overfed dogs who cavorted in the swamps surrounding their Massachusetts home and otherwise slumped under the kitchen table waiting for my grandmother to put together meals of breakfast scraps bound with maple syrup or for treats from a cookie jar on her counter. My uncles had shambling dogs who would leap into rough water off Cape Cod to retrieve balls from seaweed choked waves. As their fur dried, they smelled of sour salt water and general funk. At the rented house, they showed a gentle deference to humans and lolled on the grass or carpet while my cousins and I ate and talked. Having taught Philosophy for 46 years in three Universities—two State and one private—and never taught a Critical Thinking course one might have some questions about my choice of topic. My response is two-fold. First, there is a sense in which no matter what the topic of a particular course philosophy is always about critical thinking. One’s lectures are intended to model careful, reflective thought, sensitive to both the considerations favoring one’s views as well as the strongest objections. Second, because it is always going to be essential to use and define essential logical terminology.

Having taught Philosophy for 46 years in three Universities—two State and one private—and never taught a Critical Thinking course one might have some questions about my choice of topic. My response is two-fold. First, there is a sense in which no matter what the topic of a particular course philosophy is always about critical thinking. One’s lectures are intended to model careful, reflective thought, sensitive to both the considerations favoring one’s views as well as the strongest objections. Second, because it is always going to be essential to use and define essential logical terminology.

For a Baptist, the Bible exists like gravity. Not believing in gravity will not change the outcome if you step off a building; not believing the Bible will not change the consequences if you ignore its precepts and commands. Both are laws of nature, fixed and unchanging.

For a Baptist, the Bible exists like gravity. Not believing in gravity will not change the outcome if you step off a building; not believing the Bible will not change the consequences if you ignore its precepts and commands. Both are laws of nature, fixed and unchanging.

Few topics have captured the attention of the internet literati more than the topic of Jordan B. Peterson. Peterson,

Few topics have captured the attention of the internet literati more than the topic of Jordan B. Peterson. Peterson,

What follows is part of a collaborative project between a historian and a student of medicine called “The Temperature of Our Time.” In forming diagnoses, historians and doctors gather what Carlo Ginzburg has called “small insights”—clues drawn from “concrete experience”—to expose the invisible: a forensic assessment of condition, the origins of an idiopathic illness, the trajectory of an idea through time. Taking the temperature of our time means reading vital signs and symptoms around a fixed theme or metaphor—in this case, the circus.

What follows is part of a collaborative project between a historian and a student of medicine called “The Temperature of Our Time.” In forming diagnoses, historians and doctors gather what Carlo Ginzburg has called “small insights”—clues drawn from “concrete experience”—to expose the invisible: a forensic assessment of condition, the origins of an idiopathic illness, the trajectory of an idea through time. Taking the temperature of our time means reading vital signs and symptoms around a fixed theme or metaphor—in this case, the circus. Beauty has long been understood as the highest form of aesthetic praise sharing space with goodness, truth, and justice as a source of ultimate value. But in recent decades, despite calls for its revival, beauty has been treated as the ugly stepchild banished by an art world seeking forms of expression that capture the seedier side of human existence. It is a sad state of affairs when the highest form of aesthetic praise is dragged through the mud. Might the problem be that beauty from the beginning has been misunderstood?

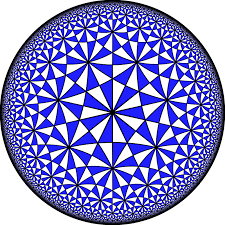

Beauty has long been understood as the highest form of aesthetic praise sharing space with goodness, truth, and justice as a source of ultimate value. But in recent decades, despite calls for its revival, beauty has been treated as the ugly stepchild banished by an art world seeking forms of expression that capture the seedier side of human existence. It is a sad state of affairs when the highest form of aesthetic praise is dragged through the mud. Might the problem be that beauty from the beginning has been misunderstood? There is a famous exchange in Casablanca between Rick (Humphrey Bogart) and Captain Renault (Claude Rains):

There is a famous exchange in Casablanca between Rick (Humphrey Bogart) and Captain Renault (Claude Rains):