Toby Mulligan. Portrait, January 2018.

Though we are an aggregator blog (providing links to content elsewhere) on all other days, on Mondays we have only original writing by our editors and guest columnists. Each of us writes on any subject we wish, and the length of articles generally varies between 1000 and 2500 words. Our writers are free to express their own opinions and we do not censor them in any way. Sometimes we agree with them and sometimes we don’t.Below you will find links to all our past Monday columns, in alphabetical order by last name of the author. Within each columnist’s listing, the entries are mostly in reverse-chronological order (most recent first).

by Akim Reinhardt

It’s an exhaustive list. Far longer and deeper than you might suspect. The Tribune tracks U.S. school shootings of the past 50 years. A well documented list by Wikipedia goes back to 1840, when a student named Joseph Semmes shot University of Virginia law professor John Anthony Gardner Davis.

Three more school shootings occurred in the 1850s, when guns were substantially different weapons than they are now. The revolver had been invented in the 1830s, and rifles were beginning to replace muskets, but Hiram Maxim’s machine gun was still decades away. And even when they did arrive, automatic weapons were initially quite expensive and difficult to obtain. In response to the gangland violence of the Prohibition Era (1920-33), the federal government effectively regluated automatic weapons with the 1934 National Firearms Act.

Consequently, even as public school education expanded greatly in the United States after the Civil War (1861-65), documented school shootings were sparse and resulted in relatively few deaths for the remainder of the century.

Decade — (No. of School Shootings) — Deaths/injuries

1860s ——————–(6) ———————————8/1

1870s ——————–(7) ———————————4/4

1880s ——————–(11)———————————2/6

1890s ——————–(8)———————————13/19+

Many school shootings from the 1860s-1950s did not unfold they way we now picture them, with a single gunman mowing down masses of people. Indeed, guns were not even always the preferred weapon. More often, American school violence involved knives and fists. As for school shootings, many resulted from spontaneous fights.

In 1893, a fight erupted at a high school dance in Plain Dealing, Louisiana. Two students died on the scene, two more were fatally wounded, and a teacher was also injured.

That same year, six people were killed and at least one injured at a high school in Charleston, West Virginia when one group of students interrupted another’s performance. A teacher intervened, the antagonizing group turned on him, and then other people joined the fray, resulting in a violent melee. The teacher and five others were shot and killed, and one student died from having his skull crushed. Read more »

by Leanne Ogasawara

On May 11th, to mark the 100th anniversary of Richard Feynman’s birth, Caltech put on a truly dazzling evening of public talks. I heard that tickets sold-out online in four minutes; and this event was so popular that attendees started queueing up to enter the auditorium an hour before the program began. Held in Caltech’s Beckman Auditorium (the white, perfectly round hall designed by legendary architect Edward Durrell Stone that students sometimes call “the wedding cake”), the line buzzed with excited conversation as people could be heard telling various anecdotes about Feynman. There are so many of Feynman stories! Just as we were about to be let in, I overheard one that always makes me smile; so perfectly does the story capture what Feynman is to Caltech. A gentleman behind me was talking to a friend about his days as an undergraduate at the Institute. He said that he would never forget the time when an upper class-man had explained to him the workings of Caltech’s highly streamlined bureaucracy:

On May 11th, to mark the 100th anniversary of Richard Feynman’s birth, Caltech put on a truly dazzling evening of public talks. I heard that tickets sold-out online in four minutes; and this event was so popular that attendees started queueing up to enter the auditorium an hour before the program began. Held in Caltech’s Beckman Auditorium (the white, perfectly round hall designed by legendary architect Edward Durrell Stone that students sometimes call “the wedding cake”), the line buzzed with excited conversation as people could be heard telling various anecdotes about Feynman. There are so many of Feynman stories! Just as we were about to be let in, I overheard one that always makes me smile; so perfectly does the story capture what Feynman is to Caltech. A gentleman behind me was talking to a friend about his days as an undergraduate at the Institute. He said that he would never forget the time when an upper class-man had explained to him the workings of Caltech’s highly streamlined bureaucracy:

“Basically at Caltech,” the upper class-man had informed him, “There are six division heads who report directly to the provost; who himself only has to answer to the President.”

Amazed at how minimal departmental management was at the institute, he had asked, “Is that it?”

To which his interlocutor had immediately replied: “Well, of course, the president does have to answer to God; who then must answer to Richard Feynman.”

It’s true that Feynman is absolutely venerated at Caltech. When he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1965, a group of Feynman devotees (aka students) used a ladder to climb up and reach a bas relief sculpture that adorned a high exterior wall in the patio at Dabney House. The sculpture was loosely modeled on Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper and depicted a group of nine scientists (including Newton, Copernicus, Pasteur, Franklin, Archimedes, Euclid, Darwin and Da Vinci) who were gathered around a table with the great Galileo in the center. The students in their excitement over Feynman’s win, proceeded to remove Galileo’s name, replacing it with that of Feynman’s. And no one has dared put Galileo back since! Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Sarah Firisen

30 years ago I moved from the UK to New York City and I gave up my car. I had mixed feelings about doing so at the time – I was only 21 and driving was still a novelty and an expression of independence. When I moved out of New York City to upstate 13 years later, I again became a car owner and regular driver. After my divorce, when I moved back to New York City, I once again gave up my car, this time happily. I would honestly be thrilled if I never had to get behind the wheel of a car again. I don’t enjoy driving, I’m not the most confident driver (I cannot reverse to save my life even after over 30 years of driving) and I generally would prefer to be driven. My transportation needs are now taken care of by a combination of public transport, ride sharing services and a boyfriend with a car who is very good about driving me around. And thanks to online shopping, the retail convenience of a car ownership has almost totally disappeared. As far as I’m concerned, this is a perfect state of affairs.

30 years ago I moved from the UK to New York City and I gave up my car. I had mixed feelings about doing so at the time – I was only 21 and driving was still a novelty and an expression of independence. When I moved out of New York City to upstate 13 years later, I again became a car owner and regular driver. After my divorce, when I moved back to New York City, I once again gave up my car, this time happily. I would honestly be thrilled if I never had to get behind the wheel of a car again. I don’t enjoy driving, I’m not the most confident driver (I cannot reverse to save my life even after over 30 years of driving) and I generally would prefer to be driven. My transportation needs are now taken care of by a combination of public transport, ride sharing services and a boyfriend with a car who is very good about driving me around. And thanks to online shopping, the retail convenience of a car ownership has almost totally disappeared. As far as I’m concerned, this is a perfect state of affairs.

And it turns out, I’m not the only person who feels this way. While there is debate about just how strong a trend it is, and even exactly why it’s happening, there does seem to be a clear trend that millennials also don’t want to own cars.

Ever since Professor Clayton Christensen of Harvard University first coined the phrase Disruptive Innovation almost 25 years ago, companies have talked a lot about trying to head off disruption from entrants into their industry, and some have even taken strong action, with mixed results. But sometimes, no effort is enough, “Consider that 18 months after the introduction of the Google Maps Navigation app for smartphones in 2009, as much as 85% of the market capitalization of the top makers of stand-alone GPS devices had evaporated.” Read more »

by Evert Cilliers

The freer the market, the more people suffer.

The freer the market, the more people suffer.

Look what happened after Bill Clinton signed the two bills that deregulated Wall Street with the repeal of Glass-Steagall (the firewall between regular and speculative banking) and the removal of derivatives from all oversight: Wall Street tanked the world.

And who got bailed out? The crooks of Wall Street, not their victims.

Socialism for the rich, and capitalism for the rest of us (as MLK put it).

The free market means freedom for the rich, and oppression for everyone else.

1. Taxes

Consider taxes:

At the end of WW2, for every buck in taxes collected on individuals, Washington collected $1.50 on business profits. Today, for every buck collected on individuals, Washington gets 25 cents from business profits.

Remember that one. Sear it into your brain. Staple it on your cerebellum. Since Reagan, the tax burden has been neatly shifted from business to individual people, from GE (who never seems to pay ANY taxes in any given year) to you and me.

Then add this: the marginal tax rate on the richest individuals went from 91% after WW2 to 35% today, and is actually, for hedge fund billionaires, 15%, and for the second richest American, Warren Buffett, 17% (as he never tires from pointing out, “my secretary pays a higher tax rate than me”). Read more »

https://youtube.com/watch?v=VUDAdOdF6Zg

A couple of weeks ago I was making my online rounds. When I checked YouTube I saw a link to a conversation between Steven Pinker and Joe Rogan. I’m quite familiar with Pinker and have correspond with him a bit, though I’ve not read his most recent book. And the name, “Joe Rogan”, set off some resonance that I couldn’t place. OK, I’ll check it out, thought I to myself. See what Steve’s up to these days and find out about this Joe Rogan guy.

It was a long and interesting conversation and, yes, it did cover Steve’s current book, Enlightenment Now, though it took awhile to get around to it. Otherwise the conversation ranged widely: flame wars on Usenet, comedy roasts, altruism, the Flynn effect, mass murderers, spiritual enlightenment, aerobics, online magazines, the long-term course of human history, the post-Trump world, and others.

I liked Rogan’s style.

The good old Wikipedia told me that Rogan had been on News Radio back in the 1990s–OK, now I know who he is–and then hosted Fear Factor earlier in this century–saw that, too, some of them. Early in his life he’d the become interested in the martial arts–karate, taedwondo, kickboxing–and had won some state and national titles. Moreover, he’s put in a lot of time as a commentator with the Ultimate Fighting Championship. AND, he’s been working at stand-up comedy all this time. He’s also into nutrition, hunting, mind expansion–cannabis, psychedelics, sensory deprivation–health and nutrition, and who knows what else.

This guy’s got some range! Read more »

by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

Fake news is a problem. That’s one thing that most people can agree on, despite the expanding breadth of their various political disagreements. So what is fake news? In their recent article in the journal Science, David Lazer, Matthew Baum, et al. define fake news as “fabricated information that mimics news media content in form but not in organizational process or intent.” That they have provided such a clean and straightforward definition is an achievement — the political vernacular is saturated with charges of fake news, and hence it’s important to introduce some precision into the discourse. This is especially the case in light of the fact that many deployments of the charge of “fake news” are what one might call politically opportunistic, that is, aimed at de-legitimating a story that has been reported as news, while also demonizing the person or agency doing the reporting. Having a precise definition of fake news is needed in order to distinguish actual instances of fake news from the cases in which the charge of fake news is invoked merely opportunistically.

However, it strikes us that the analysis above is yet lacking; there are cases that look to us like instances of fake news that are nonetheless excluded by the definition. So it may be too narrow. Consider the following case:

CRIME REPORT Putative news source (N) reports (accurately) to an audience (A) an incident (I) in which a violent crime is committed within A’s vicinity, by a group identified as Muslim immigrants.

Thus far, the original definition delivers the right result in CRIME REPORT: no fake news is in play. But let’s add to the case that N excessively reports I throughout a news cycle, and reports in a manner that could give a casual member of A the impression that several different crime incidents involving Muslim immigrants have taken place. Now, it seems to us that CRIME REPORT has become an instance of fake news. However, N’s reportage involves no fabricated information; in fact, the reportage is ex hypothesi accurate. The misleadingness might have more to do with errors arising from the availability heuristic and various priming effects than with anything in the content of the claims themselves. Moreover, it might even be the case that CRIME REPORT involves the creation of no new beliefs; the report is misleading in that it confirms or fortifies existing beliefs prevalent in A. Read more »

by Tamuira Reid

In the picture her hair is wet and stuck to her face. Her eyes struggle to stay open in the terrible wind and she’s clenching her teeth around a big rubber mouthpiece. One of her bathing suit straps has gone slightly askew, and a splash of sun-freckles cover her chest in constellation form.

In the picture her hair is wet and stuck to her face. Her eyes struggle to stay open in the terrible wind and she’s clenching her teeth around a big rubber mouthpiece. One of her bathing suit straps has gone slightly askew, and a splash of sun-freckles cover her chest in constellation form.

I don’t have a shot of her going in, how she scooted her butt to the very edge of the speedboat and lowered her finned-feet into the water. She didn’t want to do it. I had to push her.

In the picture she looks like a sea monster. She hates snorkeling. She did it for me.

In Hawaii it’s the thing to do. In Hawaii people swim underwater with the fish.

Our hotel room was on the twelfth floor and had wrap around decks and panoramic views of the island. Tourists laid in rows on the sand like strips of jerky, their bodies red and beaten by the sun.

Everything is beautiful in Hawaii. You expect the island to somehow break open at any minute, the illusion ending, ugly guts exposed. Read more »

“The piano ain’t got no wrong notes.”

~ Thelonious Monk

It’s with a certain pleasure that I can recall the exact moment I was seduced by the musical avant-garde. It was in the fourth grade, in a public elementary school somewhere in New Jersey. Our music teacher, Mrs. Jones, would visit the classroom several times a week, accompanied by an ancient record player and a stack of LPs. You could always tell when she was coming down the hall because the wheels of the cart had a particularly squeak-squeak-wheeze pattern. However, such a Cageian sensibility was not the occasion of my epiphany. I’m also not sure if fourth-graders are allowed to have epiphanies, or, which is likelier, if they are not having them on a daily basis.

It’s with a certain pleasure that I can recall the exact moment I was seduced by the musical avant-garde. It was in the fourth grade, in a public elementary school somewhere in New Jersey. Our music teacher, Mrs. Jones, would visit the classroom several times a week, accompanied by an ancient record player and a stack of LPs. You could always tell when she was coming down the hall because the wheels of the cart had a particularly squeak-squeak-wheeze pattern. However, such a Cageian sensibility was not the occasion of my epiphany. I’m also not sure if fourth-graders are allowed to have epiphanies, or, which is likelier, if they are not having them on a daily basis.

Rather, it was a record that she cued up for us one day: Henry Cowell’s ‘The Banshee’, originally composed in 1925. Originating in Irish folklore, the banshee is a female spirit whose keening announces the imminent death of a family member. Cowell sought to evoke the supernatural terror such an encounter might elicit by creating a composition for piano where no keys are actually depressed – instead, the performer plucks and rakes the strings of the piano directly. With the damper pedal pressed down, the tones so generated are freely sustained, and the adjoining wires ring out in consonant vibration, creating a rich set of overtone resonances that add to the unearthly textures that hang in the air. My fourth-grade self was transfixed, and although I can’t remember anything else we did in Mrs. Jones’s class, that occasion remains in my memory with an almost crystalline clarity. Read more »

by Jalees Rehman

Probably. Possible. Perhaps. Indicative. Researchers routinely use such suggestives in scientific manuscripts, because they acknowledge the limitations of the inferences and conclusions one can make when analyzing scientific data. The results of individual experiments are often open to multiple interpretations and therefore do not lend themselves to making definitive pronouncements. Cell biologists, for example, may test the role of molecular signaling pathways and genes which regulate the cellular functions by selectively deleting individual genes. However, we are also aware of the limitations inherent in this reductionist approach. Even though gene deletion studies allow us to study the potential roles of selected genes, we know that several hundred genes act in concert to orchestrate a cellular function. The role of each gene needs to be interpreted in the broader context of their role in this cellular orchestra. It is therefore not possible to claim that one has identified the definitive cause of cell growth or cell survival. Addressing causality is a challenge in biological research because so many biological phenomena are polycausal.

This does not mean that we cannot draw any conclusions in cell biology. Quite the contrary, being aware of the limitations of our tools and approaches forces us to grapple with the uncertainty and ambiguity inherent in scientific experimentation. Repeat experiments and statistical analyses allow researchers to quantify the degree of uncertainty for any given set of studies. When the results of scientific experiments are replicated and confirmed by other research groups, we can become increasingly confident of our findings. However, we also do not lose sight of the complexity of nature and are aware of the fact that scientific tools and approaches will likely change over time and uncover new depths of knowledge that could substantially expand or challenge even our most dearly held scientific postulates. Instead of being frustrated by the historicity of scientific discovery, we are humbled by the awe-inspiring complexity of our world. On the other hand, it is difficult to disregard an increasing trend in contemporary science to obsess about the novelty of scientific findings. A recent study analyzed the abstracts of biomedical research papers published in the years 1974-2014 and found that during the 30 year time period, there was an 880% (nine-fold) increase in verbiage conveying positivity and certainty using words such as “amazing”, “assuring”, “reassuring”, “enormous”, “robust” or “unprecedented”.

Why are some scientists abandoning the more traditional language of science which emphasizes the probabilistic and historical nature of scientific discovery? Read more »

by Shadab Zeest Hashmi

My earliest encounter with English poetry drew a subliminal connection with the Irish poets, a connection I could not easily pinpoint as a student of literature in Lahore, Pakistan, but one that re-emerged with striking clarity on my first visit to Ireland. Seeing fragments of poetry adorning hotel walls, ceilings of pubs and elevators in Dublin, I was reminded of verses of Urdu poetry on the television screen, and verses, (often sentimental or humorous ones) painted on trucks and rickshaws back when I was growing up in Pakistan. Poetry in Urdu as well as the other (“provincial”) languages— written, recited, repeated as part of ordinary speech— is a dominant part of Pakistani culture as it is of Ireland, though Pakistan has yet to produce a Nobel laureate in Literature, as opposed to Ireland whose literary laurels, both in quantity and level of prestige, are an embarrassment of riches.

While in Dublin, I came across references to the Irish movement of Independence multiple times a day; reminders of freedom from British rule punctuate the city as landmarks and shapes its psyche. The historical moment of gaining sovereignty is key not only as a constantly (and proudly) visited chapter in mainstream culture, but also as a moment that hearkens back to the nation’s great literary figures who played a pivotal role in achieving independence— a scenario all too familiar to someone from Pakistan, a country whose nationhood was first suggested by a poet. The timeline of the struggle for independence from British rule is the same (late 19th—early 20th century) for the Indo-Pak subcontinent and Ireland, as is the fact that the movement included a milieu of writers among the leaders. It is the partition of Pakistan from India and the defining and defending of a new identity that Pakistan has in common with Ireland, the “anti-partition” camp in the larger political conversation notwithstanding.

David Aberbach, in his analysis of some of the most influential poets who wrote against British Imperialism, says: “The British empire set off an explosion of poetry, in English and native languages, particularly in India, Africa and the Middle East. This poetry – largely neglected in the scholarship on nationalism – was often revolutionary both aesthetically and politically, expressing a spirit of cultural independence. Attacks on England and the empire are common not just in native colonial poetry but also in poetry of the British isles.” Some of the poets included in this work are: Tagore of India, Yeats of Ireland, and Iqbal of Pakistan. Read more »

by Dwight Furrow

If by “objectivity” we mean “wholly lacking personal biases”, in wine tasting, this idea can be ruled out. There are too many individual differences among wine tasters, regardless of how much expertise they have acquired, to aspire to this kind of objectivity. But traditional aesthetics has employed a related concept which does seem attainable—an attitude of disinterestedness, which provides much of what we want from objectivity. We can’t eliminate differences among tasters that arise from biology or life history, but we can minimize the influence of personal motives and desires that might distort the tasting experience.

If by “objectivity” we mean “wholly lacking personal biases”, in wine tasting, this idea can be ruled out. There are too many individual differences among wine tasters, regardless of how much expertise they have acquired, to aspire to this kind of objectivity. But traditional aesthetics has employed a related concept which does seem attainable—an attitude of disinterestedness, which provides much of what we want from objectivity. We can’t eliminate differences among tasters that arise from biology or life history, but we can minimize the influence of personal motives and desires that might distort the tasting experience.

“Disinterestedness” (a barbarous term but it’s the one we have to work with) refers to a kind of experience in which an object is perceived “for its own sake”, not merely for its usefulness at achieving some other goal. The idea is that in genuine aesthetic appreciation we must consider the object itself without the distraction of practical concerns or personal desires that govern ordinary life. By bracketing or suspending ordinary desires and everyday practical concerns, we are able to have a contemplative, imaginative experience that enables the full range of aesthetic properties of an object to emerge. Immanuel Kant, the philosopher most responsible for this concept, argued that the appreciation of genuine beauty is possible only via disinterested attention, which he thought of as a distinctive type of experience quite separate from everyday experience.

In professional wine evaluation this goal of disinterested attention governs the procedures used in tasting wine. Blind tasting, where tasters do not know the producer, region and in many cases the varietal, is essential to realizing this goal. So is the use of standardized assessment criteria, agreed upon aroma and flavor grids, the practice of spitting to avoid excess alcohol consumption, etc. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

Editor’s Note: Mohammed Hanif published a review of this film in Urdu at the BBC. A translation into English by Zahra Sabri is published below with Mr. Hanif’s permission. The film is the definitive story of Abdus Salam, the first Pakistani to win the Nobel prize. It captures in vivid detail his life’s journey—from a small village in Pakistan to worldwide scientific acclaim—and his fraught relationship with his homeland, where he faced rejection for being a member of the “heretical” Ahmadiyya movement.

by Mohammed Hanif, translated by Zahra Sabri

Dr Abdus Salam had once said, “It became quite clear to me that either I must leave my country or leave physics. And with great anguish, I chose to leave my country.”

Dr Abdus Salam had once said, “It became quite clear to me that either I must leave my country or leave physics. And with great anguish, I chose to leave my country.”

I heard these words in what is probably the first documentary film ever to be made on the life of the Nobel prize-winning Pakistani physicist Abdus Salam. The producers of the film are two young men from Pakistan, Omar Vandal and Zakir Thaver. I’ve been hearing these young men go on about Salam since some ten years. They have been labouring over the film for more than a decade.

I had suspected that these two men might lose interest in this topic similar to the way that the whole nation of Pakistan has washed their hands of Salam, having labelled him a kafir. However, their efforts have borne fruit and the film Salam: The First ***** Nobel Laureate is ready for screening.

The asterisks in the title stand in for the space where the word ‘Muslim’ should have been, but since this word has been expunged from the inscription above his grave in the town of Rabwah, the filmmakers have used asterisks to describe Salam so as to evade the possibility of a fatwa. Read more »

by Ashutosh Jogalekar

A new theory seldom comes into the world like a fully formed, beautiful infant, ready to be coddled and embraced by its parents, grandparents and relatives. Rather, most new theories make their mark kicking and screaming while their fathers and grandfathers try to disown, ignore or sometimes even hurt them before accepting them as equivalent to their own creations. Ranging from Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection to Wegener’s theory of continental drift, new ideas in science have faced scientific, political and religious resistance. There are few better examples of this jagged, haphazard, bruised birth of a new theory as the scientific renaissance that burst forth in a mountain resort during the spring of 1948.

A new theory seldom comes into the world like a fully formed, beautiful infant, ready to be coddled and embraced by its parents, grandparents and relatives. Rather, most new theories make their mark kicking and screaming while their fathers and grandfathers try to disown, ignore or sometimes even hurt them before accepting them as equivalent to their own creations. Ranging from Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection to Wegener’s theory of continental drift, new ideas in science have faced scientific, political and religious resistance. There are few better examples of this jagged, haphazard, bruised birth of a new theory as the scientific renaissance that burst forth in a mountain resort during the spring of 1948.

April 2, 1948. Twenty-eight of the country’s top physicists met at the Pocono Manor Hotel near the Delaware Water Gap in Pennsylvania. Kept apart from their first love of fundamental research in physics by the war, they were eager to regroup and rethink the problems which had plagued the heights of their profession before they were called away for war duty to Los Alamos, Cambridge and Chicago.

The listing of participants provides a rare snapshot of one of those hallowed transitions in the history of science, a passing of the torch. Both the old and the new guards were there. The old guard was represented, among others, by Niels Bohr, Paul Dirac and Eugene Wigner – the men who had formulated and then shaped the material world in its quantum mechanical image during the 1920s and 30s. The new guard was represented by Richard Feynman, John Wheeler and Julian Schwinger – the swashbuckling young theorists who wanted to take quantum theory to new heights, even if it meant challenging the old wisdom. J. Robert Oppenheimer who led the conference represented a prophet of the middle ground; a guide joining old hands with new. In retrospect, a clash of worldviews seems almost inevitable. Read more »

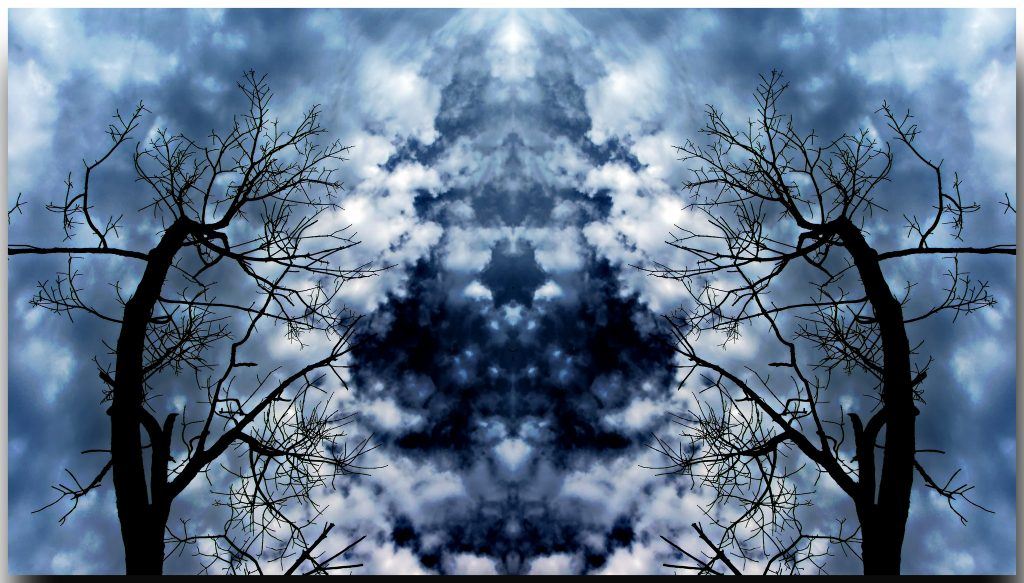

Derek Parfit. Untitled (Thundercloud), c1980s .

C type digital print.

Current show “The Mind’s Eye” at Narrative Projects, London, organized by Owen Laub with Samuel Sokolsky-Tifft. (Thanks, Sam).

by Gabrielle C. Durham

“Griselda was fighting against the patriarchy the only way she knew – through her unquenchable lust for venison.”

“Griselda was fighting against the patriarchy the only way she knew – through her unquenchable lust for venison.”

A romance or porn writer I am not, but what should strike you, other than the inappropriate sexualization of wild game, is the utterly superfluous preposition “against.” Why can’t Griselda simply fight the patriarchy? Why fight against? You got me, but the overprepositioning of English is driving me batty.

Why does this bother me? The short answer: Because it’s filler. Overprepositioning is the equivalent of “um, like, you know” without the obvious signposts of verbal dimness. If someone adds prepositions without regard to verbs, with no consideration of whether such appendages are required, then you are in the unsure-footed presence of a mediocre bullshitter. This is a writer who does not care about conventions such as transitive or intransitive verbs, dog-word-piling, or even the linguistic niceties that lubricate our written conventions. No, this writer is a cliché-spewing toad who only warrants pity for being ignored by a merciless editor.

If we were all native Turkish speakers, this would make so much more sense. Turkish is agglutinative, so prepositions are built into all the action. My Turkish friend who speaks English beautifully visibly falters with some predicate constructions. His tendency is to pile on the prepositions. Using prepositions feels so alien to him that he adds them scattershot to sentences. He becomes that hammer who sees every direct object as a nail. Read more »

by Brooks Riley