by Michael Liss

Some Presidencies just come apart: The men occupying the office are objectively unable to manage the chaos around them. Herbert Hoover’s might be thought of as in this category. James Buchanan’s as well. Perhaps Jimmy Carter’s. Others, like Richard Nixon’s, die of self-harm, unmourned. Still others end in “fatigue”—their party, or the public, essentially tires of them. Harry Truman’s flirtation with running for a second full term fell victim to Estes Kefauver, Adlai Stevenson, and a mostly uninterested Democratic Establishment. George Herbert Walker Bush found “Message: I care” not quite as compelling as he had hoped. Sometimes the public, or just the Party, wants a change.

What separates the survivors, the people who seek and succeed both at the job itself and the politics of getting reelected? It’s certainly not being free of the seven deadly sins. Nor is it being above politics. It’s a core philosophical anomaly of our system that our Chief Executive is charged with acting on behalf of all citizens while being the political leader of half. That takes, along with the talent, intelligence, and temperament to get the job done, a certain moral agility, a selective application of standards of right and wrong, sometimes even to the extent of muting the dictates of conscience. Presidents are in the business of making choices, often ones where there are shades of grey rather than clear bright lines, and, to make these choices, they have to call upon their own resources, both light and dark.

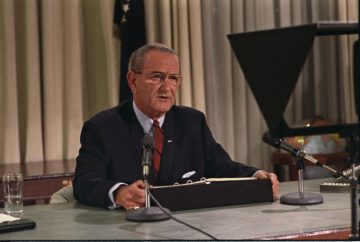

If you could somehow take samples of DNA from every President, good, bad and indifferent, and run them through a centrifuge, you might, might come up with a sample that resembles Lyndon Baines Johnson. A complex, contradictory man with a complex and contradictory record. Read more »