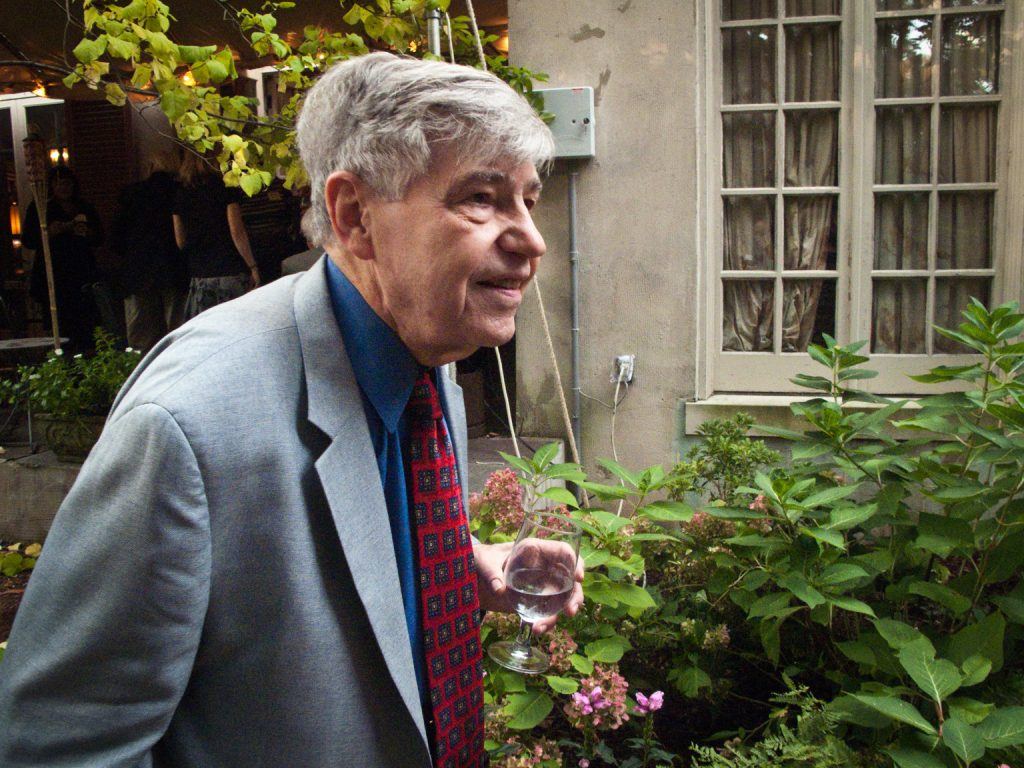

While cruising the web on the evening of July 22, 2019, I learned that Dick Macksey had died earlier in the day. He was a legend at Johns Hopkins University, had been for years – a prodigious polymath who speaks who knows how many languages, a tireless teacher, a genial host, and an indefatigable conversationalist who owns more books than the Library of Alexandria, though only a few of them are quite that old. Everyone had spoken of the legend for decades, and Everyone is now retelling it.

The thing about legends is that they are based in fact, but the amplification serves to create distance from facts behind the legend.

I had worked with Macksey for seven years between 1966, the spring of my freshman year at Johns Hopkins, and the fall 1973, when I went to SUNY Buffalo to get a doctorate in English literature. I have had occasional contact with him since then, both in person and over the phone. I knew the legend of course. But I also glimpsed the man.

Progression through digression

I don’t know why I took Prof. Macksey’s course, The Autobiographical Novel, in the spring of 1966. Sure, I liked to read. But there must have been other literature courses I could have taken–for all I know maybe I took one of them. That was a long time ago, over half a century. If I were to offer you memories of Macksey in those years would I really be reporting what I’d seen and heard or would I simply be giving you the legend as it has been passed down and embroidered?

Truth is, I probably took the course in part because I HAD heard the legend, about this cool professor who spoke a zillion languages, had read everything and owned half of it, could talk his way from Baltimore to Towson (just north of Baltimore for those who don’t know the area) by way of Lubbock, Timbuktu, Paris, Moscow, and Dublin, and who smoked a pipe. What’s to tell, strictly from memory?

I more or less forget what we read, but I’ve been reconstructing the list. Gradually. Likely St. Augustine’s Confessions, definitely Remembrance of Things Past (I’d never heard of Proust), A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (nor Joyce either), Slaughterhouse Five, Tristes Tropiques, an abridged translation–my introduction to Lévi-Strauss, The End of the Road–John Barth had left Hopkins for Buffalo by that time. And for sure Tristram Shandy. Now there’s a Macksey novel, progression by digression, Laurence Stern’s method and Macksey’s too. I remember he brought a first edition to class – a little stack of smallish books.

And he would hand out a chronology for each author. Each one. In each course.

The Idea of the Theater – took that in the fall of ‘66. Did a paper on Oedipus at Colonus; used a chart in that paper. I got the idea from Lévi-Strauss’s 1955 essay, “The Structural Study of Myth”–perhaps an optional rather than a required reading. When did I learn about Roman Jakobson’s poetic function? The Idea of the Picaro (Lazarillo, Simplicius, Moll Flanders, Felix Krull, Gully Jimson, Gnossus Pappadopoulis, who else?)–forget just when I took that one. Which course had Naked Lunch? Northrup Frye’s Anatomy? When had Girard lectured on mimetic desire? I may have taken another course with Macksey, in fact I did, a history of literary criticism–is that where we read Longinus? For sure I did an independent study, but I don’t remember the rationale, as if that mattered. It was with Macksey.

Somewhere during that time there was a visit to his house–one of many–where I saw Whitehead and Russell’s three-volume Principia Mathematica stacked on a chair. My audiophile friends were impressed with the Macintosh tube amplifier. I was impressed by the oriental carpets.

To be honest–dare I admit this?–every once in awhile the intellectual virtuosity was more annoying than dazzling. For one thing after a few years I’d heard some of the riffs before. And sometimes you just wanted a drink of water, not the whole damn reservoir sluiced at you through a fire hose–to invoke Milton Eisenhower’s line about asking Macksey a question that’s an important prop in the Macksey legend. I mean, come on Prof. Macksey, get to the point.

By that time, though, I was hooked. One summer I was writing long letters, often very long letters. And I decided to insert digressions within digressions and to mark the embedding with parentheses (like this). I must have rambled some of those sentences out for half a page or more and five levels deep. It was fun. It has only just occurred to me that I must have absorbed that from Tristram Shandy via Macksey (or vice versa). But at the time I certainly did not think that’s what I was doing–at least I don’t think so. Remember, that was a loooong time ago. I was just playing around. Progression through digression.

Anyhow, I got my undergraduate degree (in philosophy) on time, the spring of 1969, and stuck around for a couple of years to get a master’s degree through the Humanities Center. This was during the Vietnam era and I’d drawn a 12 in the draft lottery. I was going to be called up. I applied for conscientious objector status and got it. I did my alternative service in the Chaplain’s Office at Johns Hopkins while writing a long and somewhat shocking thesis on “Kubla Khan”, shocking in that it was an inventive structuralist analysis conceived at a time when structuralism was dying the death of a thousand cuts. Macksey directed the thesis and saw me off to Buffalo for a doctorate. I visited Macksey two or three times after that when I was visiting Hopkins and have had some phone calls with Dick now and then.

Mary Douglas on Tristram Shandy

One of them came late in 2003. Most likely I’d called him to talk about anime, which I’d recently discovered. I don’t have any explicit record of the call, no notes, no phone bill. But I know I talked with him about anime and, judging from some emails I’d sent, that must have been when I made the call.

I believe Dick had seen Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away, which had played in theaters in the States, he was not generally acquainted with anime. For that matter, I don’t really know how much I knew at the time, but certainly Spirited Away, a couple other Miyazaki films, My Neighbor Totoro, probably Princess Mononoke, and anime by others as well, Ninja Scroll, Akira, Ghost in the Shell, perhaps Card Captor Sakura and Revolutionary Girl Utena. I was excited. He was interested.

He suggested I read The Electric Animal, by Akira Lippit–a friend, former student? I forget. It was indeed useful, about why animals-as-people seemed to dominate cartoons early in the 20th century (moving from the country to the city left us hungry for contact with animals), and about one particularly gruesome episode in early cinema, the electrocution of the elephant Topsy in 1903–Google it to see a clip–which proved suggestive in thinking about those electric elephants in the “Pink Elephants on Parade” sequence of Dumbo.

Somehow we got to talking about Mary Douglas, the anthropologist who was in some ways the British counterpart to Lévi-Strauss. Perhaps I’d mentioned her simply because I’d been corresponding with her following the publication of my book on music, Beethoven’s Anvil, which she had been kind enough to blurb. Or perhaps because she and I had talked about anime and manga when I visited her at Yale, where she was in residence to deliver the Tanner Lectures. One of those lectures was to be about Tristram Shandy, and she’d sent me a draft.

It turned out that Dick needed to fill a slot in the issue of MLN (Modern Language Notes) which had been due at the press yesterday, if not before. Perhaps she’d be interested in publishing her Tristram Shandy paper with MLN? I asked her. A bunch of emails, a few late night phone calls. Yes-no maybe sorta’. It was just a little complicated and a little frantic, by my standards if not by Dick’s. It didn’t take all that much time, it was just the pace and odd hours. The issue needed to go to press and it would be really nice to include an essay by Mary Douglas. Alas no.

The incident made it clear that the Macksey-behind-the-curtain worked really hard. Of course, anyone who knows him knew that he worked hard. How else could he get it all done, teaching four, five, six courses–and on two campuses (Arts and Sciences at Homewood in North Baltimore, the Medical School in East Baltimore), advising the Chaplain’s Office on films (not to mention hosting discussions of them in his library screening room), the editing, the correspondence, the guests, and who knows what else? His family, Catherine and Alan! But here I’d been in the middle of the maelstrom. I’m tempted to say that I felt just a bit like Mickey Mouse drowning in that whirlpool of freely associating brooms in “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice”. But it was Macksey himself who was riding the waves and there was no sorcerer to calm the waves. He just had to ride it out.

A message from a graduate student

A few years later I got a message on Facebook out of the blue. Delano Lopez was a graduate student at Ohio State doing an intellectual history dissertation that involved the 1966 structuralism conference at Hopkins. He was going through the final report in the archives of the Ford Foundation, which had funded the conference, and came across my name. I was mentioned as an undergraduate who had been particularly affected by the conference. Mr. Lopez wanted me to elaborate.

Yikes! thought I to myself, what do I say? You see, I hadn’t attended the conference. But I wasn’t particularly surprised that Macksey would have mentioned me in the report. Should I correct the record? That was one issue. There was another. As the conversation developed it seemed to me that my interlocutor had gone off track.

As I said, I hadn’t actually attended the conference. If you are familiar with the conference proceedings (The Structuralist Controversy) you might wonder how that could be, as I’m there on pages 244-245 with a comment on the paper Neville Dyson-Hudson had delivered, “Lévi-Strauss and Radcliffe-Brown”. If I wasn’t at the conference then how come I’m in the proceedings commenting on one of the papers?

Slight-of-hand, charitable subterfuge. Macksey was being kind, not so much to me–though it certainly was that–but to Dyson-Hudson. There had been discussion after every presentation, lively and even contentious discussion so I’ve read, but not after Dyson-Hudson’s. I forget why–Macksey explained it to me, perhaps it was late at night and the French were argued out?–but he thought it would be odd, if not embarrassing, to publish the proceedings and include discussion after every paper except Dyson-Hudson’s. So Macksey asked me to write a comment. After all I’d studied Radcliffe-Brown in a course I’d taken with Dyson-Hudson and I was quite familiar with Lévi-Strauss–if anyone was my main man, it was Lévi-Strauss. Of course I was pleased and flattered by the request and agreed. That’s how I ended up in the proceedings of a conference I hadn’t attended.

Was I going to tell all that to this Ohio State graduate student who’d just read the official report of that conference? I thought about it for a second or two and decided that no good purpose would be served by running that down. Too much time, a little too complicated. Yes, Macksey had fudged the proceedings and apparently he’d fudged the final report as well, but he wanted his friend Neville to be properly represented. And, for that matter, it was certainly true that the conference had affected me even though I hadn’t attended it. I’d spent several years swimming in structuralism and semiotics more or less as a consequence, not so much of the conference itself, but of the intellectual currents that had washed the French ashore in Baltimore harbor in October 1966. And I’d marked up the translation of Derrida’s paper which Macksey had distributed in class in three colors of ink! (By the way, Derrida got Lévi-Strauss wrong, but that’s irrelevant here.)

At the same time you can see, can’t you? why I wasn’t at all surprised that Macksey had mentioned me in his report to the Ford Foundation.

OK, so I’m not going to tell Mr. Lopez what really happened. What do I say in answer to his question?

Here’s where he’d gotten it a bit sideways. What it comes down to is that he wanted to know how the conference, its interdisciplinary nature in particular, changed my sense of the humanities. What do you mean, changed? I tried to tell him. Johns Hopkins was all I knew about the humanities in the American academy. Remember, I’d arrived at Hopkins from a decent high school in small city in the coal and steel country western Pennsylvania. Sure, I heard talk from Macksey and others that Hopkins was different, but that’s all it was to me, just talk about things I’d never experienced. Hearsay. So, while yes the conference had been important to me, it didn’t change my perception of the academy. It was my baseline, my point of departure, my ground zero.

I’m not sure Lopez quite got the force of my point.

Whatever.

Delano did see an earlier version of this piece which I’d posted at my New Savanna blog. He told me that he’s finished his degree and is headed to Miami University in Ohio on a Visiting Assistant Professorship in American studies.

A six year old on the moon

Now we’re back at the beginning. On the evening of July 22nd I learned that Macksey had died. What did I do? I searched the web. I found Cynthia Haven’s piece, “Farewell Richard Macksey, legendary polymath and ‘the jewel in the Hopkins crown’ (1931-2019)”[1], and Kate Dwyer’s, “Meet the Man Who Introduced Jacques Derrida to America”[2], and I found some oral history material[3] at the Hopkins Library dating from 1999 when one Mame Warren had interviewed him.

Hot damn! I thought, the Macksey story from Macksey hisownbadself. But it was mostly about the history of Johns Hopkins, founding years and then mid 20th century. Here’s Macksey on Charles Sanders Pierce (from the transcript, p. 5):

The appointment of Charles Peirce came two years later-I lose track-and Peirce was, again, a profoundly eccentric person who was here five years and I think you could make a pretty good case that Peirce was the most broad-gauged and creative mind that the American Academy had in the nineteenth century, but this was the only formal academic appointment he ever held. He had grown up at Harvard, and his father, Benjamin Peirce, was a great mathematician of the preceding generation. President Elliott couldn’t stand him, so he was not welcome around the precinct.

He had worked for the Geodetic Survey, did important work there, and presented himself as really almost a university in and of himself and, of course, long term we look to Peirce as the sort of-if not the father, the grandfather of semiotics, modem semiotics. Semiology, he called it. His work in mathematics was, I think, both profound and important, but because he published very little, much of this material doesn’t appear. The only monograph he published in his lifetime was a pendulum-swinging affair. But he was the candidate for professor of philosophy, which wasn’t an appointment that was made immediately.

Macksey taught Pierce when he taught semiotics. I think, though I’m not sure at this point, that he believed Pierce’s account of sign to be superior to Saussure’s much better known account.

But there was some autobiography (p. 16):

Warren: What attracted you here in the first place? Macksey: Fort Holabird. This is during the Korean War, so I didn’t know Baltimore well. When I was in college—I was an undergraduate at Princeton—I had been down to visit Baltimore, and it was very, to me, exotic and Southern town, but they were doing interesting things in sciences, and originally I was interested in sciences. They had just started a Department of Biophysics, Detlev Bronk, and they had a medical school and interesting things going on in the pure sciences. So these are things that looked real good to me.

And I had thought of Hopkins all my life, because when I was very, very little, about six or seven, I sort of solved some problems by saying I wanted to be a doctor. “Where are you going to go?” Well, it was always Hopkins. So there was an unexamined kind of Hopkins connection.

But after I got here, I then sort of drifted over into literary things. This is no great loss to the sciences, to be sure, but it was partly possible because it was such a small place.

That explains why the Tudor and Stuart Club[4] had been so important to Macksey. It was a literary society with monthly meetings on the Homewood campus that been founded, however, through an endowment from Sir William Osler, one of the founders of The Johns Hopkins Hospital. The speakers were chosen alternatively to represent the arts and sciences one month and medicine the next. Again, bridges between the disciplines, those pesky “two cultures”.

Now, let’s run through that again, in a different version, but also from 1999. This is from an article that had appeared in the Hopkins Gazette[5]:

“You needed a profession, and we didn’t have any medical people in my family, so I said, sure, I’m going into medicine,” Macksey says. “It got adults off your back when you said you were going to study medicine. And then I gradually realized that it was a way to give meaning to your life—or at least to make a plausible story.”

Bingo! “It got adults off your back.”

And he’s been doing it all his life. It’s the “adults” who insist that knowledge be divided into disciplines each carefully insulated from one another. It’s the inner six-year-old who insists that, since the world isn’t like that, inquiry shouldn’t be like that either. It was the inner six-year-old who piloted those flights of intellectual fancy that propelled the Macksey legend, demonstrating that it’s the knowledge that matters, not you or me or Milton Eisenhower. Macksey’s got the chops to fly us to the moon and back.

So there.

Certainly that’s what so many of his students needed from him. We were quite serious about whatever it is – truth, beauty? – Hopkins could offer us. We just didn’t like the strictures that came with the offering. Macksey gave us room to breathe, to explore, to grow.

Of course you didn’t actually have to study with him to benefit from his generosity. Knowing that Macksey held the work of Samuel Delany in highest regard, and that Delany was acquainted with him, I mentioned his death to Delany on Facebook. He responded:

He was very kind to me on a number of occasions although I only met him once when he came to write a review of my department when I first started teaching in the Comparative Literature Dept. of the University of Mass. at Amherst. In fact, possibly I wouldn’t have had my entire academic career.

Think about that. Samuel Delany is one of the best and best-known science fiction writers in the world. Richard Macksey was…what? “Fan” isn’t quite right. We’re talking about a mature adult, but…why not? This particular adult is a six-year old who rode his 70,000 book library to infinity and beyond. Yes, a fan. Dick Macksey was a fan of Chip Delany.

Now conjure me this: A course taught by Delany and Macksey in which each picks half the texts.

Beam me up!

[1] http://bookhaven.stanford.edu/2019/07/farewell-richard-macksey-legendary-polymath-and-the-jewel-in-the-hopkins-crown-1931-2019/

[2] https://lithub.com/meet-the-man-who-introduced-derrida-to-america/

[3] https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/handle/1774.2/37788

[4] See William Benzon, “Old School: Torpor and Stupor at Johns Hopkins”, 3 Quarks Daily, Nov. 13, 2017, https://3quarksdaily.com/3quarksdaily/2017/11/old-school-torpor-and-stupor-at-johns-hopkins.html

[5] https://hub.jhu.edu/2019/07/23/richard-macksey-profile-gazette/