by Philip Graham

Although my love of music goes back to the glory days of the long-playing vinyl album, I’ve embraced all the succeeding platform incarnations, from tapes to CDs to downloading to streaming (well, not so much streaming—shame on you, Spotify, for disappearing musicians’ royalties down to the teeniest fraction of a penny). But I hate to confess that while I can recognize a modulation, I’d be hard pressed to tell you from what key to the other. My knowledge of musical notation remains shaky, and sometimes I can’t distinguish between an alto and a tenor saxophone on a recording. I never learned to play an instrument. When clapping along at a singer’s request (remember those ancient concert rituals?), I begin cautiously, afraid to undermine the rhythm of my neighbors. I can’t even snap my fingers. So why imagine I can write about music?

I don’t know what exact percentages of nitrogen, oxygen, argon, carbon dioxide and water vapor make up the air, but still I breathe. And I will inhale any genre of music with delight. In a movie theater I sometimes wait to the end of the interminable final credits so I can locate the name of a song whose snippet in a minor scene erased for me the rest of the film. All my books have been written with music offering a friendly counterpoint—each page holds the echo of a secret playlist.

I almost never hesitate to track down an intriguing, unfamiliar song. It’s impossible to predict when such a moment will arrive. Certainly there was no warning that night near the end of my last semester at college. The threat of graduation had reared up too quickly, and with a sense of doom I parked myself at a free table in the school’s library—always a cozy place to study, tucked as it was (some might say crammed) into the first floor of one of the oldest buildings on campus, its presence nearly lost beneath the two upper floors reserved for dorm rooms.

A handful of books by the poet W. S. Merwin, along with a sheaf of handwritten notes, lay strewn across my study table. For this particular final research paper (there were others waiting in line), I had a notion that Merwin’s translations of Amazonian oral literature might have influenced the breakaway style of his book, The Lice. Maybe this idea would prove fruitful, maybe not. But I had little chance of dredging up any further insights while someone in a dorm room above cranked out music so loud that the guilty stereo system could have been invisibly set up in the study area.

At least the music—jazz with a Latin twist—oozed a sleek, muscular beauty. An electric piano traded solo runs with a flute, a soprano’s ethereal voice joined wordlessly, and the drummer—a master of the lightest of touches—established the groove with a nimble-fingered bassist. On and on it went, solo after chorus after solo after hand-clapping breakdown, until the song wrapped up with a full-band flourish.

Then, silence.

Seconds later, the music began again.

Oddly, not a soul sitting at the other tables groaned or lifted their eyes in annoyance. Perhaps we all secretly enjoyed the slow, gorgeous electric piano introduction, stately and melancholic. Then the main melody took over and sped up, serpentine, rising, rising, yet with the bittersweet, downward pull of a minor key, and when the flutist and vocalist paired in harmony, the flute became a human voice and the voice became a flute. The solos careened through the melody’s possibilities and, my god, did it all swing, for at least ten minutes until that final fanfare.

Silence.

I thought, Thank you, secret musical benefactor, even if you’re preventing any progress on this research paper—

The scratchy crunk of a needle touching vinyl announced the show was about to begin again. By this third round, the slowly unfolding electric piano introduction sounded increasingly familiar. I must have encountered some version of this melody before, but where? The memory clung to its hiding place.

That mysterious amateur DJ couldn’t keep playing this song indefinitely, and then, when would I ever hear it again? If I wanted to find out the name of this song, this band, then I’d better get off my butt and follow its trail. In 1973, that’s what you had to do. Tapping the Shazam app on a smart phone screen, to serve up the title and artist of the latest haunting earworm so you could then go about your business, remained a future undreamt dream.

Even today, success is not assured. Once while parked in a Chicago café, I noticed that a particularly lovely ballad from the piped-in music had entered its slow fade. I pulled out my phone, tapped in the password, and opened the Shazam app, but by the time that little pulsating “S” icon appeared, the song had slipped to silence. The barista knew less than I did. “It’s just our radio feed,” he said. Even though not a scrap of that tune has stuck with me, to this day I can still fully taste my disappointment at losing it.

Seven, maybe eight more minutes remained before that jazzy rave-up would end. Abandoning my books on the study table, I hustled out the library’s entrance and paced back and forth along the building’s Tudor brick façade. The air hummed, vibrated with the song, yet no window, open or closed, obviously served as a woofer and tweeter.

I have to confess, in those days I occasionally opened my own dorm window and blasted out music to entertain and enlighten whoever passed by. Yeah, I was that guy. I understood how music can fill you with such joy you can’t contain it any more, you have to release it, even if that means stupidly cranking up your stereo—an earlier era’s annoying, pre-digital form of file sharing.

I kept pacing beneath the few lit windows. As usual for the weekend, most of the campus had migrated to New York City. Maybe the elusive impresario lounged in the cave of a dark room. Impossible to tell! There wasn’t much time left, and I couldn’t count on the song repeating a fourth time. I ran back into the building and up the stairs to the second floor. I’d knock on every door if necessary.

No need, if I simply followed the bass to its loudest booming. Halfway down the hallway, it pulsed through the ceiling—so, third floor. I scrambled up another flight of stairs and made my way to a door that, remarkably, hadn’t yet loosened its hinges.

I knocked, first politely, then louder, but the music inside overwhelmed my efforts. Maybe an alternating pattern might catch the music lover’s attention, so I knocked in cross rhythm to the bass.

The doorknob rattled, the door swung open. A young woman stood before me, her face all curiosity and innocence.

“Um, I was downstairs in the library—”

“Oh! Is the music too loud?” Behind her, the air hovered cloudy and pungent. That probably explained her difficulty acing the volume dial.

I nodded.

“I’m so sorry, I’ll turn it off.”

“No! I mean, please, keep it on,” I said. “The music’s . . . wonderful. Could you tell me what it is?”

She stepped back into her room and returned with the album jacket, its cover graced by a feather, hovering somewhere above the stratosphere and below the words Chick Corea and Return to Forever. The album’s name? Light as a Feather.

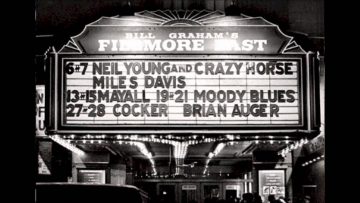

Chick Corea. I knew that name . . . he’d played electric piano on Miles Davis’ Bitches Brew. Three years earlier, I’d seen Davis debut that album for a New York audience at a Fillmore East triple bill.

Miles and his group had been unfairly sandwiched in between the opening act, the Steve Miller Band, and the headlining Neil Young and Crazy Horse. I don’t recall much of the Miller Band’s set, except that the original quintet had skeletoned down to a trio and smoothed out whatever passion their songs once possessed with a peppy efficiency. Who could have predicted that their biggest hit, “The Joker,” still lay ahead of them?

Miles Davis’ group followed, its haunting electric propulsion stopping, starting, twisting, turning, and music’s two polys—rhythmic and tonal—dueted on some tilt-a-whirl imaginary dance floor, team-tagging body and soul. From the theater’s balcony I’d watched Miles Davis and his band unfold the music’s ferocious beauty until I simply closed my eyes and listened, surrendering to yet resisting its harsh and elegant syncopated flow. When a new world is offered to you, it can both exhilarate and unsettle.

Young and Crazy Horse followed. Inspired by the challenge, they banged out the ragged glory of their folk-rock best, but it didn’t amount to much more than dim lights unable to penetrate the rich nurturing darkness that Miles Davis had conjured for us. Don’t get me wrong, I’ve long admired Neil Young (“Cinnamon Girl” was one of the records I used to so kindly blast out my window for lucky passersby). But. He shouldn’t. Have been. The headliner.

Chick Corea had played in that Miles Davis band, and he’d clearly spent his time well, learning how to combine his own opposites, deftly employing serious jazz chops to defy gravity, leaving the rough and ready energy of a Willie Colon or a Tito Puente far below.

I glanced up from the album cover. The young woman still stood patiently in the doorway, her smile faint but her eyes ripe with an emotion I recognized: savoring a moment of unambiguously converting someone to music she adored. I further recognized that she was probably okay with the risk of disturbing an entire dormitory and library for a coup so rare. One day, I too might be capable of perpetrating a similar stunt. Wasn’t I already on that path?

Unsettled, I handed back the album jacket. I wanted to get away but first needed to ask one remaining question. “So, which song on the album is this?”

“It’s called ‘Spain.’”

I thanked her and left. I’d found what I’d been searching for, but also something I hadn’t expected—an inadvertent gift that served as a warning. The look on her face had too closely mirrored my own impulses and revealed an uncomfortable truth that would haunt me for some time. Yet little did I know my frantic search that evening would also serve as a loose template for my life’s future musical obsessions. Years later, I hurried with my wife through the maze-like alleys of a working-class neighborhood in Ivory Coast’s up-country city of Bouaké, hoping to locate the source of a different sort of glorious music ringing out from somewhere nearby—what turned out to be the Cuban-influenced rumba of Congolese soukous music.

But that’s another story.

When I finally returned to the library’s study area, the song galloped to its final notes. Had it really been less than ten minutes since I’d left?

In the silence, I announced, in case anyone was interested, “It’s ‘Spain,’ by Chick Corea.” They must have guessed what I’d been up to. They deserved a report.

A few people nodded. A couple more wrote it down.

Someone murmured, “Thank you,” and a little bit of that young woman’s satisfaction echoed in me as the electric piano once again resumed its achingly beautiful and melancholic steps.

Coda

The following day, as I stood in line at the local Sam Goody’s record store, holding my copy of Light as a Feather, I realized from the jacket’s musician credits that Brazilian singer Flora Purim and drummer Airto Moreira had added some of their own country’s lilt to the record’s Latin pedigree. But “Spain” wasn’t titled “Spain” for nothing. After countless listens, it finally dawned on me that Corea had adapted his piano intro from the Adagio of the Concierto de Aranjuez for guitar and orchestra, by the Spanish composer Joaquín Rodrigo. Miles Davis, too, had recorded a version on “Sketches of Spain,” his collaboration with composer and arranger Gil Evans.

To get back to basics, here’s a sterling example of Rodrigo’s Adagio, performed by guitarist Tariq Harb and the Orchestre Symphonique de l’Isle.

Bonus Coda

Wait, there’s something else.

As a kid, my favorite movie was 1961’s lushly melodramatic, medieval epic, El Cid, because of a) Sophia Loren, my biggest pre-adolescent crush, and b) the movie’s “Love Theme” by composer Miklós Rózsa (so, maybe that b is merely a variation on a . . .). Though Hungarian-born Rózsa’s melody is different from Rodrigo’s Adagio, it circles the same star. I sometimes wonder if, as I persisted in my long-ago quest through the library building, that melody I couldn’t quite identify served as a hidden path to a moment of childhood pleasure, a brief attempt to sidestep the looming college graduation I wasn’t quite prepared to face.

Here, violinist Daniel Hope solos with the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra.