by Deanna K. Kreisel

Now that Americans are emerging, blinking, into the post-pandemic daylight (perhaps temporarily! let’s not get too excited), a certain amount of stock-taking has been taking place. Some of it is braggadocious (languages learned, abdominal muscles honed), some of it is tragic (loved ones lost, livelihoods curtailed), and some of it is chagrined (Netflix queues emptied, drinking problems acquired). I am one of the lucky ones: a knowledge worker who was able to hunker down at home, with no children to wrestle and pin down in front of Zoom cameras; I lost no people and no material thing of importance. But that doesn’t mean that I escaped entirely unscathed. I have been cultivating a shameful new addiction in the secrecy of my own home, one that overcame me during the pandemic and still has me pinioned in its cruel, vise-like grip. My name is Deanna K., and I am a New York Times Spelling Bee addict.

It started innocently enough. My partner Scott and I used to do the New York Times crossword together all the time; during the pandemic lockdown, we got into the habit of stumbling out of our studies after hours of Zooming in order to eat lunch at the kitchen counter, and I would bring my iPad so we could do the crossword while we ate. Then, one fateful day, Scott noticed the bright yellow-and-black bumblebee logo on the Puzzles page, invitingly twitching its plump little bumblebutt at us like a schoolyard pusher offering a free taste. We gave it a go, found it intriguing and just the right amount of maddening, and were completely sucked in. Read more »

When I finished my residency in 1980, I chose Medical Oncology as my specialty. I would treat patients with cancer.

When I finished my residency in 1980, I chose Medical Oncology as my specialty. I would treat patients with cancer.

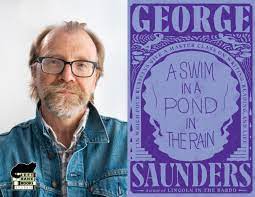

George Saunders’ recent book, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, is the most enjoyable and enlightening book on literature I have ever read.

George Saunders’ recent book, A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, is the most enjoyable and enlightening book on literature I have ever read.