by Claire Chambers

Ghazal poetry is an intimate and relatively short lyric form of verse from the Middle East and South Asia. The form thrives in such languages as Arabic, Persian, Urdu, and now English. Like the Western ode, these poems are often addressed to a love object. Influenced by ecstatic Sufi Islam, the ghazal’s subject matter concerns desire for another person and, figuratively, love for the Divine.

Indeed, a mixture of sacred, profane, romantic, and melancholic elements are frequently stitched into the ghazal’s poetic fabric. Many ghazals revolve around the theme of lovers’ separation. This topic also functions as an image for the Muslim worshipper’s longing for Allah. In doing so, the ghazal draws comparisons with seventeenth-century metaphysical poetry. Like ghazalists, John Donne would ostensibly write about love for a woman but also shadow forth devotion to God.

Sound, rhyme, repetition, and rhythm come to the forefront in this form. This makes it unsurprising that many ghazals have been turned into songs. For instance, during the course of his illustrious poetic career, Mohammad (‘Allama’) Iqbal (1877–1938) wrote dozens of ghazals. Some of these poems have been set to music. They were sung by popular South Asian musicians including the late Mehdi Hassan and Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, as well as contemporary singers Lata Mangeshkar and Sanam Marvi. I also think of the famous playback singers Noor Jehan’s and Nayyara Noor’s renditions of the poetry of Faiz Ahmed Faiz (1911–1984). This crossover often surprises Westerners: it’s as though Carol Ann Duffy’s poems were being sung by Rihanna!

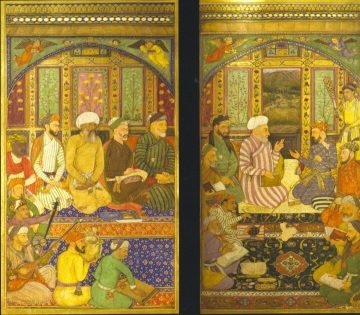

In the Muslim world, the arts are less likely to be locked away in compartments or considered elitist as they are in the West, and more likely to be part of everyday life. In the Indian subcontinent and its diaspora, mushairas (meaning ‘gathering of poets’) are interactive poetic meetings. These recitals, with their call and response tradition, have made the ghazals an instantly recognizable form in the popular consciousness. Because of this accessible performative and musical tradition, working-class South Asians have nearly as much access to poetry as the elite.

As a Marxist, Faiz took the themes of love and mystical yearning for God, and imbued them with politics. The ghazal no longer only concerned desire and the ineffable, but ‘any ideal to whom or to which the poet … is prepared to dedicate himself’. Under Faiz’s pen this ideal was social responsibility to the poor, and the shared lives of all members of a community.

Even as early as the mid-nineteenth century, the ghazal poet Mirza Ghalib (1797–1869) would take the stock images of Urdu poetry to create something new. He made veiled but acerbic points about the turbulent time in which he lived, the era of the Indian Rebellion of 1857 and the demise of the Mughal Empire. As in Faiz’s later work there is an important dialogue between love and loss in Ghalib’s writing, especially in his threnodies for the decline of a culturally syncretic Mughal history and his descriptions of a historical moment when Muslims were made other. The Rebellion was the turning point to which Ghalib responded, after which colonial powers increasingly represented Indo-Muslims as strangers and aggressive figures of terror in ways that are strangely familiar because of current geopolitics.

Even as early as the mid-nineteenth century, the ghazal poet Mirza Ghalib (1797–1869) would take the stock images of Urdu poetry to create something new. He made veiled but acerbic points about the turbulent time in which he lived, the era of the Indian Rebellion of 1857 and the demise of the Mughal Empire. As in Faiz’s later work there is an important dialogue between love and loss in Ghalib’s writing, especially in his threnodies for the decline of a culturally syncretic Mughal history and his descriptions of a historical moment when Muslims were made other. The Rebellion was the turning point to which Ghalib responded, after which colonial powers increasingly represented Indo-Muslims as strangers and aggressive figures of terror in ways that are strangely familiar because of current geopolitics.

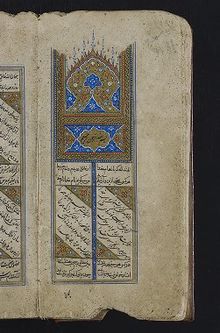

Rich images can be found in Urdu ghazals: tropes include the moth and the flame, stars and diamonds, and the rose and the nightingale. Such leitmotifs from ghazal poetry have various connotations (relating to such issues as politics, love, and religion) to different people in particular contexts.

It is also important to rebut attempts to constrict Islam into an exclusive, singular identity. This would be a distortion of the religion’s pluralist history. By noticing the opulence associated with Urdu poetry, one realizes that Islam is a diverse religion and culture. In the ghazal tradition, wine, the cup-bearer, and the Beloved are daring spiritual metaphors.

In modern-day Britain and the United States, ghazals have become a popular form. Here, they sometimes touch on a migrant’s yearning for home and belonging. The year before he died, the Kashmiri-American poet Agha Shahid Ali (1949–2001) published Ravishing DisUnities, a collection of ghazals mostly by fellow Americans (though Faiz sneaks in) from G. S. Sharat Chandra to Adrienne Su. Chafing against the free-verse liberties new world poets had previously taken with the ghazal, he exhorted contributors to return to structural ‘form for form’s sake’, while reinvigorating the form in the fresh language of English. As a Pakistani-American poet from the next generation Shadab Zeest Hashmi puts it in her beautiful nonfiction book Ghazal Cosmopolitan, ‘[t]he ghazal fuses the old with the new, the friend with the stranger – reflecting, refracting, and constantly reminding us that America to is a convergence of sorts, a cultivation of diversity – at least the promise of it’. Clearly, this is a pliable poem stretched across a firm fixture, like a tent’s canvas to its metal frame.

The ghazal is made up of semi-autonomous couplets, each of which helps to set up the logic of the whole poem. The form is notable for its rhyme, the symmetry of its couplets, and a radif or refrain at the end of the second line of each couplet. The late American poet John Hollander explained the controlled structure through his witty ‘Ghazal on Ghazals’:

For couplets the ghazal is prime; at the end

Of each one’s a refrain like a chime: “at the end.”

But in subsequent couplets throughout the whole poem,

It’s this second line only will rhyme at the end

One such a string of strange, unpronounceable fruits,

How fine the familiar old lime at the end!

As the image of the string suggests, another metaphor often used to explain the centrifugal and centripetal forces of the individual couplets and the poem as a whole is that of a necklace. The  linguist Sir William Jones (1746–1794) famously and patronizingly portrayed the ghazal as ‘Orient pearls at random strung’. Two centuries later Agha Shahid Ali would elaborate on this, while tacitly discounting Jones’s idea of randomness: ‘One should at any time be able to pluck a couplet like a stone from a necklace, and it should continue to shine in that vivid isolation, though it would have a different lustre among and with the other stones’. The tight schema is maintained even when what is being discussed, as with Faiz, is political violence or social disintegration. No wonder, then, that Ali speaks oxymoronically of a ‘stringently formal disunity’.

linguist Sir William Jones (1746–1794) famously and patronizingly portrayed the ghazal as ‘Orient pearls at random strung’. Two centuries later Agha Shahid Ali would elaborate on this, while tacitly discounting Jones’s idea of randomness: ‘One should at any time be able to pluck a couplet like a stone from a necklace, and it should continue to shine in that vivid isolation, though it would have a different lustre among and with the other stones’. The tight schema is maintained even when what is being discussed, as with Faiz, is political violence or social disintegration. No wonder, then, that Ali speaks oxymoronically of a ‘stringently formal disunity’.

Excerpts from these poems are almost a cultural currency, substituting for feelings too painful to be articulated. Even today many South Asians readily filigree everyday conversation with quoted couplets.

The takhallus is the pen name that is evoked in the final couplet, lending the ghazal a sense of intimacy. In the first ghazal Ali ever wrote, he ends with an explanation of his middle name’s significance in Arabic, that language which has been extolled in the radif of each of the foregoing couplets:

Listen, listen: They ask me to tell them what Shahid means:

It means ‘The Beloved’ in Persian, ‘witness’ in Arabic.

To take another example, at the end of her ‘Ghazal: Song’, Shadab Zeest Hashmi hails herself using her equally resonant middle name (Zeest being the Persian word for ‘life’):

The last of your days, Zeest, were splintered, cut short by the axe of words

On your prosaic deathbed you pray for someone to pour the syrup of song

Such poets fuse the ghazal with the modern world, overspilling national boundaries. While the ghazal’s esoteric allusions continue to the present day, recent ghazalists like Hashmi bend the seemingly unmalleable structure and open up the form to new audiences.

It is clear that this millennia-old poetic form continues to be revised and re-energized even as its core remains unchanged. To quote John Keats, with his ghazal-friendly celestial image, ‘Bright star, would I were stedfast as thou art’.