by Adele Wilby

Nothing focuses minds like grave events that bring about severe disruption to everyday living. Over recent times, two major happenings, one with global and the other with more regional implications, have jolted people out of their complacency and compelled some reflection on unpredictability and uncertainty in life, and what is going on around us.

Nothing focuses minds like grave events that bring about severe disruption to everyday living. Over recent times, two major happenings, one with global and the other with more regional implications, have jolted people out of their complacency and compelled some reflection on unpredictability and uncertainty in life, and what is going on around us.

Firstly, the coronavirus pandemic has concentrated governments and the people throughout the world on measures to control this previously unknown deadly virus that has taken the lives of hundreds of thousands of people and infected more than double that amount in the process. The ‘lockdown’ of entire populations in a bid to starve the virus of hosts for its reproduction has been the key strategy adopted by many governments in dealing with this lethal viral infection. People have stayed at home, ‘lock-downed’, and travelling has been brought to a halt. ‘High’ and ‘low’ and all those in between have had to garner themselves for tough times behind closed doors, cutting themselves off from loved ones and friends as the most effective strategy of containment of the lethal potential of this minute protein invisible to the human eye.

The second issue that has jolted the thinking of many people across the globe, particularly the western liberal world, stems from the recent murder of an innocent black man, George Floyd, by the police in Minneapolis, in the United States (US). The video of this man being viciously and callously murdered by a white police officer as he pleaded for his breath has appeared in all forms of social media throughout the world, sparking widespread abhorrence, condemnation, anger, and for many, utter rage. The image of the US as a liberal, just society with solid institutions based on equality and fairness has been shaken, perhaps irreparably shattered. Tragically, this is not the first incident of police officers killing black men in the US, but it is an incident that proved to be the straw that broke the camel’s back and set off widespread protests across the US and in many other countries in sympathy and solidarity with the US protestors. The murder and subsequent protests have placed racism more generally and institutionalised racism in the United States once again to the fore, elevating it to one of the hottest topics in US politics today.

These two phenomena, social isolation through ‘lockdown’ and racism, might appear to be distinct social issues, but for some the two are experienced in tandem. For many African Americans incarcerated in solitary confinement in US prisons, social isolation and racism constitute their everyday milieu, more frequently for years rather than weeks and months as is the case with social distancing ‘lockdowns’.

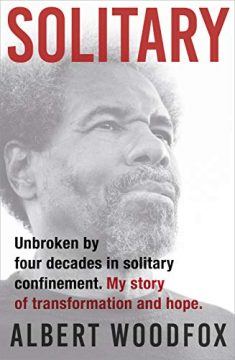

By sheer coincidence at home isolated amidst the lockdown in the United Kingdom, I had the time to read Albert Woodfox’s autobiography Solitary: Unbroken by Four Decades of Solitary Confinement: My Story of Transformation and Hope. The book narrates the impact on the individual when the two issues of social isolation and racism operate in unison. Woodfox’s autobiography brings together his story of enduring 23 hours of the day in a 3 foot by 9 foot cell over four decades in solitary confinement, and the institutionalised racism in the judicial and prison systems he and others were subjected to: the book it is a damning indictment of those two important institutions in the US. The reading of the book also puts into perspective the phenomenon of lockdown that millions have been subjected to over recent times. As disruptive to normal life as the lockdown has been, most of us at least endured the process in the comfort of our homes, not locked away in a tiny concrete cell, and indeed many could at least take a stroll downtown to do some shopping, nor did most of us have to worry about racist assault. Furthermore, we all knew the situation would eventually improve, but for most prisoners locked away in solitary confinement, none of those possibilties are available, nor is there a lapse in racist assault and abuse to which they are subjected.

The chapters in the book are divided into decades chronologically ordering Woodfox’s forty years in the Closed Cell Restricted (CCR), solitary confinement, in Angola prison in Louisiana, and therefore documents not only Woodfox’s experience of living prison life, but the history of the injustices in the legal and prison system; it is also a record of the constant racist violence perpetrated on black prisoners by prison officers. But apart from the chronological structure of his autobiography, the book can also be seen as having two parts: the early chapters and the remainder of the book.

The early chapters highlight just how deeply racism has been a phenomenon for Woodfox throughout his life. As young as twelve years old in the late 50s Woodfox ‘knew the police picked up the men in our neighbourhood because they were black and for no other reason’. Nevertheless, so repetitive are the early chapters of his history of crime that the reader begins to lose some sympathy for him as he misses the possibility for an alternative life after an initial short term in prison, and he falls more deeply into criminality and is in and out of prison in his late teens and early twenties.

It is at Chapter 10, ‘Meeting the Black Panther Party’, when we see a change in tone in his narrative, and this reflects the turn in Woodfox’s approach and attitude to life, and this makes Woodfox’s story so interesting. Woodfox shifts from being an immature felon constantly at odds with the law and the police, to a mature, self- educated man with a clarity of thought on the dynamics of injustice and the workings of racism, coupled with a steely determination to resist such practices while retaining his dignity and humanity.

The shift in his approach is attributable to his becoming aware of members of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defence during a period out of prison. Founded in 1966, the initial aim of the organisation was to stop the police brutality in black neighbourhoods, but the members in the organisation impressed Woodfox with their assertion of their own self-respect and the help provided to members of the community.

Woodfox’s changing attitude was strengthened during his solitary confinement when he learned a member of the Black Panther Party, Robert King was in the same prison in 1970. King was serving a sentence of thirty-five years for a murder he was eventually cleared of. King’s self-respect and consideration for his fellow prisoners coupled with the literature provided by King to Woodfox aroused in him a passion for knowledge and he became a veracious reader consuming a wide range of literature, including that on law. Ultimately, it was the example set by King and his knowledge that, ‘…only education would save us…Education and looking forward…we had to keep learning and keep our minds focused on the world outside Angola’ that he was able to rise above the constant barrage of racist violence and abuse that he and his fellow prisoners were routinely subjected to. Commenting on his turnabout after coming into contact with members of the Black Panther Party at the age of twenty-four Woodfox says, ‘I was a black man with a long prison sentence ahead of me. Inside, everything had changed. I had morals, principles, and values I never had before…In the past, I had done wrong. Now I would do right. I would never be a criminal again’.

With the deeper knowledge of the social and economic forces that underpinned the racism that the African Americans were subjected to, and knowing that he was no longer on the path of criminality, Woodfox considered himself a political prisoner, ‘not in the sense that I as incarcerated for a political crime, but because of a political system that had failed me terribly as an individual and a citizen…’ Herman Wallace, a man he established a long enduring friendship with while in prison, and Robert King, saw themselves in similar terms.

The Black Panther Party eventually collapsed, but not the inspiration and principles of the Party held by Woodfox, Wallace and King. Ultimately, the trio’s fight against their convictions for murders and the obstructions and delays in the legal process leads to no other conclusion than the three were being punished for their refusal to bend to the system, and for their determination to assert their humanity and self-respect, all informed by the their self-education and the principles of the Black Panther movement: they were indeed political prisoners.

Lawyers came and went throughout the processes of the many legal challenges the three submitted, but it was a junior lawyer who stumbled on Woodfox’s file and took up his case that was a turning point in the legal process for them. Ultimately other lawyers agreed that the three men had grounds to challenge their convictions, and the reasons for their prolonged imprisonment could be attributed to institutionalised racism and their political views.

The three Black Panther men became known as the Angola 3 as global support for their cases and their freedom gained momentum. Robert King was eventually freed from prison after a successful appeal against his murder conviction after spending 29 years in solitary confinement. Herman Wallace died a few days after gaining his freedom: he had spent 41 years of his life in solitary confinement. In 2016 Albert Woodfox, after much agonising following the advice from his legal team, finally submitted a ‘plea for freedom, not justice’ when he agreed to ‘nolo contendre’, ‘no contest’ in a retrial. The plea did not amount to admitting guilt but meant acknowledging that the state might have enough evidence to convict him at retrial, even though Woodfox believed that the evidence was insufficient. However, he was not prepared to take the risk of failing to get his conviction for murder overturned and then being condemned to prison for the remainder of his life. After four decades in solitary confinement, Woodfox walked from Angola prison in February 2016, a free man.

When asked, after his release, if he could identify changes in America he replied: ‘I see changes, but in policing and the judicial system most of them are superficial’ as the death of Georg Floyd demonstrates. He then proceeds to list the numbers of African Americans shot dead by the police. In 2016, he writes that African Americans were incarcerated five times the rate of whites, that African Americans and Latinos make up approximately 32 per cent of US population, but they make up 52 per cent of incarcerated people. He was encouraged to see that at least five states had taken measures to end solitary confinement and others were interested in alternative programmes to that form of punishment. Yet in 2019 at the time of publication of his book, 80,000 men, women and children were in solitary confinement across the US. Both King and Woodfox have become advocates for the ending of solitary confinement since their release.

His years of reading and politics while in prison become apparent also when Woodfox identifies the system responsible for the largest prison population in the world in the US: the prison-industrial complex. ‘Money’, he says, ‘is made off prisoners’ backs…In some prisons, inmates are forced to work full-time making products for multinational corporations for almost no pay… In some states, prisoners aren’t paid…It’s legal slavery…Under the 13thAmendment prisoners are slaves of the state and are treated as such…’, certainly an issue not to be ignored.

When questioned about the things he would change in his life, Woodfox replied, ‘Not one thing’. His years of imprisonment and in solitary confinement, he wrote, made him the man he became. What is remarkable is how, despite the social isolation and the relentless physical and verbal violence and humiliation by the state’s prison authorities that he endured, there is neither a hint of bitterness nor hatred from Woodfox throughout the book, reminiscent of the history of Nelson Mandela’s years in prison. Indeed, in his forties, decades away from his release Woodfox had learned that ‘…I still had moments of bitterness and anger. But my then I had the wisdom to know that bitterness and anger are destructive. I was dedicated to building things, not tearing them down’.

Woodfox’s book makes for compelling reading on many levels: it is a personal testimony to the experiences of solitary confinement and the injustice and intractable institutional racism and racial violence experienced by an African American when in custody; it is testimony to the potential of human beings to transform themselves; it documents the triumph of the human spirit amidst adversity and how it is possible for a human being to transcend gratuitous cruelty and humiliation, and survive with dignity and humanity intact. In the present context of the coronavirus pandemic, it also gives perspective to the phenomenon of social isolation to which many of us have been exposed over recent months. His prolonged period of social isolation was certainly experienced by him in far greater terms than any of us could imagine, and it was complicated and intensified by the added struggle of enduring systematic and protracted racism. As I read this book, I was comforted by the knowledge that my experience of the lockdown paled in significance: all I had to do was wait it out in the comfort of my home before life would soon get back on track.