by Ali Minai

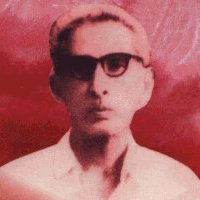

Majeed Amjad (1914 – 1974) is considered one of the most important modern poets in the Urdu language. He was born in Jhang, which is now in Pakistan, and spent most of his life in the small towns of Punjab, away from the great literary centers of Urdu. Perhaps this was one factor in giving his poetry a distinctive style and idiom that is impossible to place within any of the mainstream contemporary movements in Urdu poetry. Amjad's style is characterized by striking images, unexpected connections, and a very personal voice. He had a challenging life, with financial insecurity, domestic problems and literary frustrations. His philosophical and introspective nature drew upon these challenges to create a unique mixture of sweetness and bitterness that makes him one of Urdu's most original poets. Starting out with traditional forms, Amjad experimented extensively with new ones, and much of his later poetry is in free verse.

Majeed Amjad (1914 – 1974) is considered one of the most important modern poets in the Urdu language. He was born in Jhang, which is now in Pakistan, and spent most of his life in the small towns of Punjab, away from the great literary centers of Urdu. Perhaps this was one factor in giving his poetry a distinctive style and idiom that is impossible to place within any of the mainstream contemporary movements in Urdu poetry. Amjad's style is characterized by striking images, unexpected connections, and a very personal voice. He had a challenging life, with financial insecurity, domestic problems and literary frustrations. His philosophical and introspective nature drew upon these challenges to create a unique mixture of sweetness and bitterness that makes him one of Urdu's most original poets. Starting out with traditional forms, Amjad experimented extensively with new ones, and much of his later poetry is in free verse.

I have chosen to translate poems by Amjad because, despite the acknowledgment of his stature in literary circles, he is not as well known among general audiences as his great contemporaries, Faiz and Rashid. I chose these three poems based purely on personal preference, though they are also quite representative of his work. In particular, they capture his characteristically mysterious allusions, where he seems to refer to something particular without specifying exactly what it is, leaving the reader to infer multiple scenarios. Personally, I find this to be both aggravating and interesting – and a very modern aspect of his work, occasionally bordering on the surrealistic. The poems also have a lot of psychological nuance, which was another distinguishing feature of Amjad's poetry.

In the original, the first two poems are in metered verse and the third in free verse. While I have tried to follow the general structure of the poems, I have not attempted to translate strictly line by line, preferring to capture the thought rather than the form. In this sense, the translation is not literal, though it is quite close with minimal reinterpretation of metaphors, etc. As with all translations, it is impossible to capture all the nuances of the original. I just hope that the translated versions have sufficient interest in their own right and convey some of Amjad's uniquely mysterious, imagistic and elegiac style.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Poem 1: Superficially, this poem starts out as an elegy on the grave of some unknown poet, with the usual symbolism associated with such poems. But as one reads on, it becomes clear that this is not about any particular poet at all, nor is it an elegy. It is rather a fierce critique of that poetic tradition – long dominant in Urdu – that seeks to create art for art's sake, and has little time for the actual lives of individuals and societies. In this, Amjad is making the same point that many of his Progressive contemporaries – notably Faiz – made about the received poetic tradition in Urdu. But Amjad's allusive and imagistic style contrasts strongly with the explicit protests found in the work of the Progressives. The build-up through this poem culminates lines that send chills down the spine.

Amjad has been called a poet of brutal realism. In some of his poems, this realism is explicit, but here it is couched in a more symbolic – perhaps more appealing – form.

Voice, Death of Voice (1960)

No ornate ceiling, nor canopy of silk;

no shawl of flowers; no shadow of vine;

just a mound of earth;

just a slope covered with rocky shards;

just a dark space with blind moths;

a dome of death!

No graven headstone, no marking brick –

Here lies buried the eloquent poet

whom the world implored a thousand times

to speak out,

but he, imprisoned by his fancy's walls,

far from Time's path,

oblivious to the lightning upon the reeds,

drowned himself in the breast of a silent flute:

a voice become the death of voice!

Read more »

First, because Moses, or the prophet Musa as we know him in the Quran, is an unusual hero— a newborn all on his own, swaddled and floating in a papyrus basket on the Nile— my brothers and I couldn’t get enough of his story as children. Second, it is also a story of siblings: his sister keeps an eye on him, walking along the river as the baby drifts in the reeds farther and farther away from home, his brother, the prophet Harun accompanies him through many crucial journeys later in life, another reason the story was relatable. Returning to the narration as a young woman, a mother, I found myself more interested in the heroines in the story: Musa’s birth-mother whose maternal instinct and faith are tested in a time of persecution, the Pharaoh’s wife Asiya who adopts the foundling as her own, confronting her megalomaniac husband’s ire and successfully raising a child of slaves and the prophesied contender to the pharaoh’s power under his own roof. As a diaspora writer, especially one wielding the colonizer’s tongue and negotiating the contradictory gifts of language, I have yet again been drawn to Musa. He is an outsider and an insider— one who carries a “knot on his tongue”— the burden of interpreting and speaking, not entirely out of choice, to radically different entities: God, the Pharaoh and his own people. Among the myriad facets of the legend, the most enduring is the innocence at the heart of his mythos, the exoteric quality of wisdom explored beautifully in mystic writings and poetry as a complementary aspect of the esoteric.

First, because Moses, or the prophet Musa as we know him in the Quran, is an unusual hero— a newborn all on his own, swaddled and floating in a papyrus basket on the Nile— my brothers and I couldn’t get enough of his story as children. Second, it is also a story of siblings: his sister keeps an eye on him, walking along the river as the baby drifts in the reeds farther and farther away from home, his brother, the prophet Harun accompanies him through many crucial journeys later in life, another reason the story was relatable. Returning to the narration as a young woman, a mother, I found myself more interested in the heroines in the story: Musa’s birth-mother whose maternal instinct and faith are tested in a time of persecution, the Pharaoh’s wife Asiya who adopts the foundling as her own, confronting her megalomaniac husband’s ire and successfully raising a child of slaves and the prophesied contender to the pharaoh’s power under his own roof. As a diaspora writer, especially one wielding the colonizer’s tongue and negotiating the contradictory gifts of language, I have yet again been drawn to Musa. He is an outsider and an insider— one who carries a “knot on his tongue”— the burden of interpreting and speaking, not entirely out of choice, to radically different entities: God, the Pharaoh and his own people. Among the myriad facets of the legend, the most enduring is the innocence at the heart of his mythos, the exoteric quality of wisdom explored beautifully in mystic writings and poetry as a complementary aspect of the esoteric.