by Dwight Furrow

It seems as if everyone in the wine industry proclaims that wine tasting is subjective. Wine educators encourage consumers to trust their own palates. “There is no right or wrong when tasting wine,” I heard a salesperson say recently. “Don’t put much stock in what the critics say,” said a prominent winemaker to a large audience when discussing the aromas to be found in a wine. The point is endlessly promoted by wine writers. Wine tasting is wholly subjective. There is no right answer to what a wine tastes like and no standards of correctness for judging wine quality.

It seems as if everyone in the wine industry proclaims that wine tasting is subjective. Wine educators encourage consumers to trust their own palates. “There is no right or wrong when tasting wine,” I heard a salesperson say recently. “Don’t put much stock in what the critics say,” said a prominent winemaker to a large audience when discussing the aromas to be found in a wine. The point is endlessly promoted by wine writers. Wine tasting is wholly subjective. There is no right answer to what a wine tastes like and no standards of correctness for judging wine quality.

But no one in the wine industry actually believes this. Everyone from consumers and retail salespersons to wine critics and winemakers must distinguish good wine from bad wine and communicate that distinction to others. Ask any winemaker why she controls fermentation temperatures, and she will respond that doing so makes better wine. If wine quality were wholly subjective, there would be no reason to listen to anyone about wine quality. Wine education would be an oxymoron; quality control an exercise in futility; wine criticism just empty talk; price differentials based on nothing but marketing.

So what’s going on here? Why the self-deceptive denials and sotto voce acceptance that wine quality is a meaningful concept. We could speculate about why we’re so enamored with subjectivity—freedom from constraint in matters of taste I suppose. But it’s been going on since the 16th century, if we can blame Descartes. Read more »

On February 18, 2021, NASA landed Perseverance rover on the surface of Mars. Perseverance is the latest of some twenty probes that NASA has sent to bring back detailed information about our neighboring planet, beginning with the Mariner spacecraft fly-by in 1965, which took the first closeup photograph. Though blurry by today’s standards, those grainy images helped ignite widespread wonder and fantasy about space exploration, not long before Star Trek also debuted on television. By the 1970s, science-fiction storytelling was moving from the margins of pop-culture into the mainstream in film and television—and so followed generations of kids, like myself, who grew up expecting off-world adventurism and alien encounters almost as much as we anticipated the invention of video-phones and pocket computers and household robots, as our conceptual bounds for the human story were pushed ever farther outward.

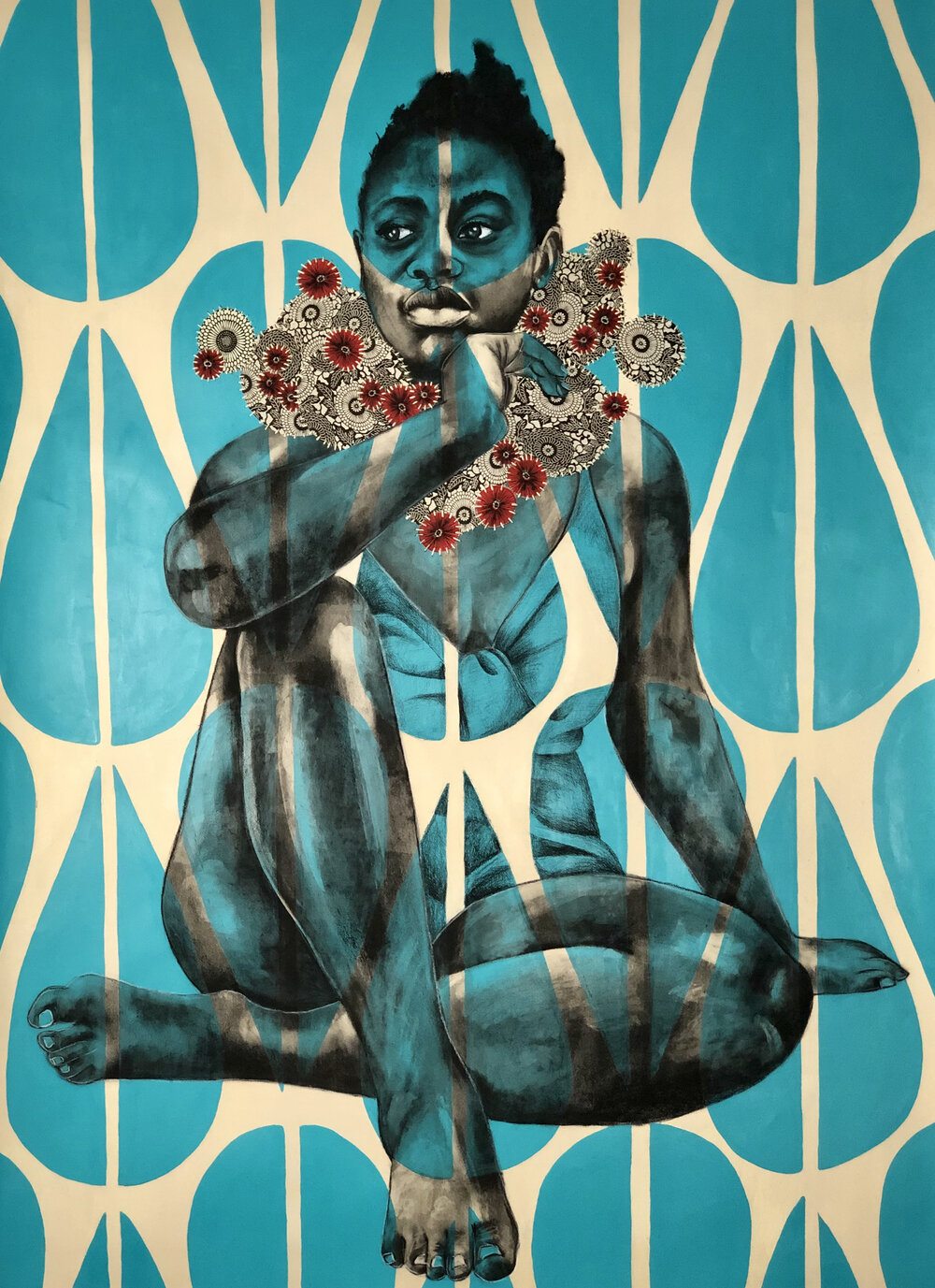

On February 18, 2021, NASA landed Perseverance rover on the surface of Mars. Perseverance is the latest of some twenty probes that NASA has sent to bring back detailed information about our neighboring planet, beginning with the Mariner spacecraft fly-by in 1965, which took the first closeup photograph. Though blurry by today’s standards, those grainy images helped ignite widespread wonder and fantasy about space exploration, not long before Star Trek also debuted on television. By the 1970s, science-fiction storytelling was moving from the margins of pop-culture into the mainstream in film and television—and so followed generations of kids, like myself, who grew up expecting off-world adventurism and alien encounters almost as much as we anticipated the invention of video-phones and pocket computers and household robots, as our conceptual bounds for the human story were pushed ever farther outward. Delita Martin. Rain Falls From The Lemon Tree. 2020

Delita Martin. Rain Falls From The Lemon Tree. 2020 It’s been 40 years this past month since the election of François Mitterrand as President of France. Today, June 21, is the day chosen by his first Minister of Culture for the

It’s been 40 years this past month since the election of François Mitterrand as President of France. Today, June 21, is the day chosen by his first Minister of Culture for the

When we were young, most of us indulged in the speculation, “What do I want to be when I grow up?” Many of us said things like a firefighter, a doctor, a nurse, or a teacher. As children, we instinctively looked at the world around us and recognized the careers that seemed to have purpose and meaning, and that seemed to make the world a better place. I can’t imagine that many 5-years olds dreamed of being paper pushers or spending their days doing data entry. But we grow up. People around us have expectations for us; we have expectations for ourselves. We might have academic challenges, financial needs, family obligations. We see the world and the careers open to us as more diverse and as more challenging than the Fisher-Price Little People figures that characterize the world for a child. And so, many of us lose that childhood idealism and just get a job, get on the career ladder, put our noses to the grindstone.

When we were young, most of us indulged in the speculation, “What do I want to be when I grow up?” Many of us said things like a firefighter, a doctor, a nurse, or a teacher. As children, we instinctively looked at the world around us and recognized the careers that seemed to have purpose and meaning, and that seemed to make the world a better place. I can’t imagine that many 5-years olds dreamed of being paper pushers or spending their days doing data entry. But we grow up. People around us have expectations for us; we have expectations for ourselves. We might have academic challenges, financial needs, family obligations. We see the world and the careers open to us as more diverse and as more challenging than the Fisher-Price Little People figures that characterize the world for a child. And so, many of us lose that childhood idealism and just get a job, get on the career ladder, put our noses to the grindstone. The desire to turn failure into a learning opportunity is often generous, and an important way of dealing with the trials and tribulations of life. I first became aware of it as a frequent trope in start-up culture, where, influenced by practices in software development where trying things out and failing is the quickest way to get to something of value, we are constantly subject to exhortations to “fail fast and fail forward”. Many workplaces now lionise (whether sincerely or not is another matter) the importance of learning through failure, and of creating environments that encourage this.

The desire to turn failure into a learning opportunity is often generous, and an important way of dealing with the trials and tribulations of life. I first became aware of it as a frequent trope in start-up culture, where, influenced by practices in software development where trying things out and failing is the quickest way to get to something of value, we are constantly subject to exhortations to “fail fast and fail forward”. Many workplaces now lionise (whether sincerely or not is another matter) the importance of learning through failure, and of creating environments that encourage this.

If you’d like to start at the beginning, read

If you’d like to start at the beginning, read

‘

‘ In

In

Jean Shin. Fallen. Installation at Olana State Historic Site, New York.

Jean Shin. Fallen. Installation at Olana State Historic Site, New York.